By B. Jeanne Billioux, MD, and Avindra Nath, MD, and edited by Chandrashekhar Meshram, MD

In this month’s neurology and COVID-19 review, we’ve included several topics that have arisen in the literature and news, including new updates regarding long COVID/PASC and neurologic outcomes of infants born to mothers with COVID-19.

In this month’s neurology and COVID-19 review, we’ve included several topics that have arisen in the literature and news, including new updates regarding long COVID/PASC and neurologic outcomes of infants born to mothers with COVID-19.

Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) or long COVID continues to be a puzzling entity. However, numerous new studies are underway to help better understand the nature of this syndrome and the mechanisms involved in its pathogenesis, including neurologic aspects.

This month, the initial findings from the University of San Diego NeuCOVID longitudinal cohort study was published, describing the neurologic manifestations in two cohorts: Patients referred to the neurology department after recovering from COVID-19, and patients with pre-existing neurologic disorders who subsequently were diagnosed with COVID-19.

In this cohort of 56 patients, fatigue was the most commonly reported symptom at baseline (89.3%), followed by headache (80.4%), insomnia (66.1%), and memory impairment (64.3%). Almost all patients had a baseline assessment at least 28 days after onset of neurological symptoms, with a median of 16 weeks from infection. In those who were able to follow up six months later, a small number (n=9) noted resolution of their symptoms, but others reported persistent fatigue (52.2%), memory complaints (68.8%), insomnia (51.3%), headache (45%), and difficulty concentrating (47.6%). However, many of these symptoms had lessened in severity.

MOCA scores generally improved over time in patients who were able to follow up (from average score of 26 to 28/30), although MOCA scores declined in about one quarter or these patients. Interestingly, a small subset of patients (7.1%) displayed a triad of symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, and cognitive dysfunction (Shanley 2022).

Another neurologic post-COVID study from Italy found that PASC patients could usually be grouped into two cohorts of PASC/long-COVID based on their neurologic symptoms. The first cohort typically presented with a constellation of memory issues, headache, psychological issues, anosmia, and ageusia; the second cohort presented with symptoms referrable to the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Upon analysis of risk factors for either cohort, the cohort with PNS-related symptoms was found to be more likely to have had a larger number of comorbidities at onset, a more severe course of COVID-19, as well as a higher number of non-neurologic COVID complications (Grisanti 2022). Longitudinal cohorts such as these will be informative for the natural history of PASC and its neurologic manifestations, as well as the potential long-term socioeconomic impact, and will help guide modes of intervention.

Several studies are ongoing to elucidate the pathogenesis of the neurologic sequelae of COVID-19. A paper published in Cell this month described diffuse microglial cell activation in the brain of patients who had died despite a mild respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2. This was replicated in a humanized mice model of a mild form of SARS-CoV-2 infection. There was no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasiveness (as evidenced by lack of virus in the CNS), however the mice displayed elevated levels of cytokines in both the serum and CSF at 7 days post-infection. Moreover, these mice were found to have increased levels of microglial/macrophage reactivity in the subcortical white matter, as well as upregulation of inflammatory gene expression in these microglia. They also found that the hippocampi of these mice had microglial/macrophage activation with impairment of neurogenesis that persisted several weeks post infection. This was accompanied by decreased levels of oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the subcortical white matter. These findings suggest that even mild infections with SARS-CoV-2 may lead to persistent neurologic inflammation, myelin dysregulation, and decreased hippocampal neurogenesis, which may lead to the neurologic symptoms currently seen in long COVID/PASC, such as memory impairment and “brain fog” (Fernández-Castañeda 2022).

Another interesting topic in the news this month is on the outcome of infants born to mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2. A cohort study of 7,772 infants, with 222 infants born to mothers who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy, found that infants born to mothers with COVID-19 during pregnancy had a higher risk of being diagnosed with neurodevelopmental abnormalities over a 12-month time period (OR 2.17), with a higher risk (OR 2.34) associated with infections during the third trimester. This risk was present after adjusting for a variety of factors, including preterm labor (which can be associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Edlow 2022). These findings warrant further evaluation, but could reflect potential detrimental effects of SARS-CoV-2-related inflammation on fetal brain development, similar to other known maternal infections. •

Avindra Nath, MD, is chief of the Section of Infections of the Nervous System and Clinical Director, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

B. Jeanne Billioux, MD, is staff clinician and head of the program in International Neuroinfectious Diseases within NINDS. Her research focus is on emerging infectious diseases and conducting research on the neurological consequences of infections in an International setting.

Chandrashekhar Meshran is co-opted trustee of the WFN.

References

Shanley JE, Valenciano AF, Timmons G, Miner AE, Kakarla V, Rempe T, Yang JH, Gooding A, Norman MA, Banks SJ, Ritter ML, Ellis RJ, Horton L, Graves JS. Longitudinal evaluation of neurologic-post acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022 Jun 15. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51578. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35702954. DOI: 10.1002/acn3.51578

Grisanti SG, Garbarino S, Barisione E, Aloè T, Grosso M, Schenone C, Pardini M, Biassoni E, Zaottini F, Picasso R, Morbelli S, Campi C, Pesce G, Massa F, Girtler N, Battaglini D, Cabona C, Bassetti M, Uccelli A, Schenone A, Piana M, Benedetti L. Neurological long-COVID in the outpatient clinic: Two subtypes, two courses. J Neurol Sci. 2022 Jun 3;439:120315. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120315. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35717880; PMCID: PMC9212262. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120315

Fernández-Castañeda A, Lu P, Geraghty AC, Song E, Lee MH, Wood J, O’Dea MR, Dutton S, Shamardani K, Nwangwu K, Mancusi R, Yalçın B, Taylor KR, Acosta-Alvarez L, Malacon K, Keough MB, Ni L, Woo PJ, Contreras-Esquivel D, Toland AMS, Gehlhausen JR, Klein J, Takahashi T, Silva J, Israelow B, Lucas C, Mao T, Peña-Hernández MA, Tabachnikova A, Homer RJ, Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Breyman E, Kontorovich A, McCarthy D, Quezado M, Vogel H, Hefti MM, Perl DP, Liddelow S, Folkerth R, Putrino D, Nath A, Iwasaki A, Monje M. Mild respiratory COVID can cause multi-lineage neural cell and myelin dysregulation. Cell. 2022 Jun 13:S0092-8674(22)00713-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.008. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35768006; PMCID: PMC9189143. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.008

Edlow AG, Castro VM, Shook LL, Kaimal AJ, Perlis RH. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 1 Year in Infants of Mothers Who Tested Positive for SARS-CoV-2 During Pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jun 1;5(6):e2215787. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15787. PMID: 35679048; PMCID: PMC9185175. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15787

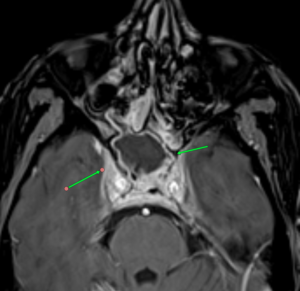

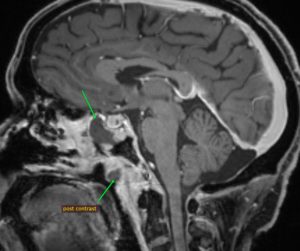

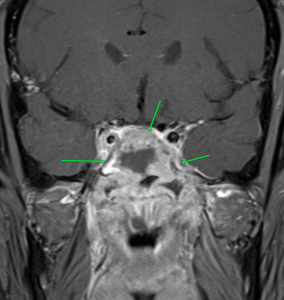

MRI images of mucormycosis with cavernous sinus involvement in a patient with COVID-19.

MRI images of mucormycosis with cavernous sinus involvement in a patient with COVID-19. The COVID pandemic had universal effects on medicine, and Mumbai was no exception. In fact, being a densely populated city with lots of international travelers, the cases appeared early and the magnitude was high, throwing the health system off gear.

The COVID pandemic had universal effects on medicine, and Mumbai was no exception. In fact, being a densely populated city with lots of international travelers, the cases appeared early and the magnitude was high, throwing the health system off gear.

This is the most important event in the last century. Arguably, aside from the tragic loss of life, the widespread and virtually simultaneous shutdown of global and regional economies, and the restriction of individual movements and travel with the enforcement of social distancing has no precedent. Wars, nuclear bombs, AIDS, global financial crises, and the threat of global warming have not done so much, so rapidly, to so many. Countries, governments, peoples, and individuals are all learning, some the hard way, that without methods to prevent the mutation of new zoonotic viruses and vaccines to combat them, public health measures are all we have to reduce the toll of human lives and the economic consequences which, in turn, also impact human life and livelihoods. The constraints effected by the implementation of public health restrictions and the unparalleled rise in the use and need for health, hospital, and ICU resources affects all aspects of health care globally and at all levels of socioeconomic standing.

This is the most important event in the last century. Arguably, aside from the tragic loss of life, the widespread and virtually simultaneous shutdown of global and regional economies, and the restriction of individual movements and travel with the enforcement of social distancing has no precedent. Wars, nuclear bombs, AIDS, global financial crises, and the threat of global warming have not done so much, so rapidly, to so many. Countries, governments, peoples, and individuals are all learning, some the hard way, that without methods to prevent the mutation of new zoonotic viruses and vaccines to combat them, public health measures are all we have to reduce the toll of human lives and the economic consequences which, in turn, also impact human life and livelihoods. The constraints effected by the implementation of public health restrictions and the unparalleled rise in the use and need for health, hospital, and ICU resources affects all aspects of health care globally and at all levels of socioeconomic standing.