e-Communications Committee and the Aphasia, Dementia, and Cognitive Disorders Specialty Group

By Wolfgang Grisold

This column focusing on WFN committees and specialty groups has a dual purpose:

- to inform and raise awareness on the important contribution of these groups for the functioning of the WFN

- to raise interest among the readers for the work of the WFN, and perhaps find and recruit persons to work closer with the WFN, in the interest of neurology.

The work of the WFN depends on the contribution of many members worldwide. Several committees support the trustees in their work (https://wfneurology.org/committees) and also develop ideas and consult. A good example is the e-Communications Committee, chaired by Walter Struhal, which identifies and helps to integrate digital technologies into the WFN. The work of this committee is summarized by Dr. Struhal.

The WFN also has several Speciality Groups, which were previously known under ARGs (Applied Research Committee https://wfneurology.org/wfn-specialty-groups). Here, the work of the Specialty Group is introduced by Suvarna Alladi, a neurology professor from India.

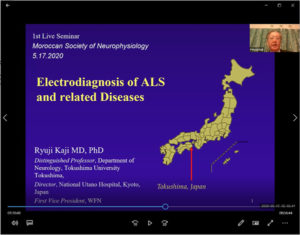

The WFN e-Communications Committee has been created to facilitate the trend of remote learning, and e-learning’s purpose is enhanced by the present COVID crisis. The new and advanced digital techniques are now rapidly evolving and will also serve to improve teaching in remote areas of the world.

WFN e-Communications Committee

Walter Struhal, MD

The origins of this committee stem from the Website Committee. Dr. Struhal got involved in this committee in 2010 as one of the founders of the worldwide young neurologists’ group—International Working Group for Young Neurologists and Trainees. Since 2014, he is in charge of the website and initiated social media channels and the WFN online footage with the close help of Chiu Man, who for more than a decade acts as WFN`s webmaster. He is assisted by Surat Tanprawate, Tissa Wijeratne and Wolfgang Grisold.

This was the early core of the current online presentation of WFN as well the roots of the present e-Communication Committee. The website was completely renewed and redesigned into a “responsive” design that allowed reader to view the same content with equal quality on mobile devices as on computer screens.

While social media increased over the years to a tremendous audience with more than 11,000 friends on Facebook, reaching with our posts from the last 30 days alone >17,000 followers, in addition to >2,700 followers on LinkedIn and >4,800 followers on Twitter.

Social media became one of the strategic core activities within WFN’s online footage and one way of reaching out to neurologists worldwide.

Today, this committee headed by Dr. Struhal consists of members worldwide (below). And the committee is actively supported by Simona Milenkova, a social media expert working for Kenes.

The main objective is continuously informing our audience on important developments in neurology on the global scale, on news from WFN, and recently in employing our growing online presence in e-Learning. One of the first meetings was the joint WFN/AFAN e-learning Day (https://wfneurology.org/2020-09-18-wfn-afan), which was well received worldwide. The large amount of information reaching this committee provides a large and challenging workload.

Aphasia, Dementia, and Cognitive Disorders Specialty Group (ADCD SG)

The WFN Aphasia, Dementia and Cognitive Disorders Specialty Group (ADCD SG) is an international community of cognitive neurologists and allied specialists dedicated to promoting research and improving clinical practice in aphasia, dementia, and other cognitive disorders globally. The group has been actively pursuing this mission since 1966 through its biennial meetings and has grown to having members from Europe, the U.K., North and South America, Australia. West, South and East Asia join its community over the years

The mission of the ADCD SG aims to stimulate scientific discussion in the field of aphasia, dementia, and cognitive disorders and to translate research findings into better assessment, management, and treatment of patients through teaching courses, biennial meetings, and participation in the World Congress of Neurology as well as other meetings. It is multidisciplinary, welcomes members of different specialties, across cultures, and seeks to collaborate with other organizations, within and outside the WFN.

Suvarna Alladi

The chair of the ADCD SG is Suvarna Alladi, professor of neurology of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences in Bangalore, India. Her clinical and research group focuses on providing multidisciplinary care for persons with dementia, cross-cultural issues in cognitive neurology, developing cognitive tests in different Indian languages and literacy levels and risk factors. Organizing community support for dementia, she co-founded ARDSI (www.ardsihyd.org) and strengthened policy for dementia (www.stride-dementia.org).

The Executive Committee is composed of distinguished experts from across continents: Prof. Morris Freedman, Canada; Stefano Cappa, U.S./Italy; Lorraine Obler, U.S.; Manabu Ikeda, Japan; Eneida Mioshi, U.K.; Peter Nestor, Australia, Matt Lambon, U.K.; Thomas Bak, U.K.; and Facundo Manes, Argentina.

The biennial meetings and teaching courses are the most impactful of the group’s activities. The first biennial meeting of the Specialty Group (formerly Applied Research Group) was held in 1966. The biennial meetings have traveled from venues in Europe to South America, Cambridge U.K., Edinburgh, and then eastward to Istanbul, Hyderabad India, and Hong Kong. The 50th anniversary meeting returned in 2016 to Lake Como, followed by Portugal and the next meeting is planned to take place in Nara, Japan.

The meetings have a tradition of putting the emphasis on quality rather than quantity and to create a forum for discussion and a genuine exchange of ideas. The symposia are based on a wide range of topics, in the traditional clinical areas in aphasia and cognitive disorders, along with newer areas in cognitive science, biomarkers, and technology.

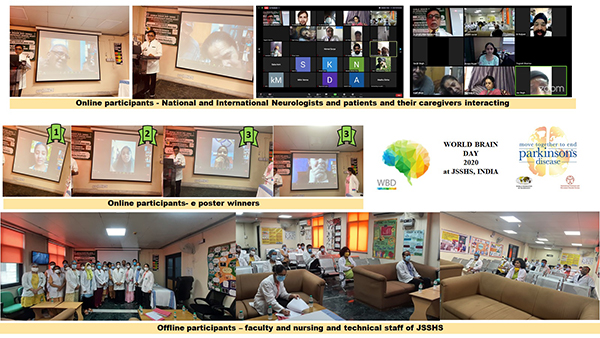

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an online sharing of knowledge and continued interaction is planned. The expert group has developed a rich clinical and research resource across multiple disciplines of cognitive neurology, cognitive psychology, psycholinguistics, speech, and language pathology among others. The SG also has a repository of cognitive-assessment tools in multiple languages, including English, Spanish, Italian, Indian languages, Chinese, and Japanese, among others.

The global expertise of the group has focused on developing joint recommendations for adaptation of diagnoses, assessments, and treatments of aphasia and cognitive disorders across the world. Through its Forum for Young Researchers (FYRE), the SG encourages and nurtures young talents globally. •

| WFN e-Communications Committee | |

| Chiu Man: | Webmaster (WFN U.K.) |

| Daniel Gams Massi: | Pan-Africa (Cameroon) |

| Laura Druce: | WFN office (WFN U.K.) |

| Maria Benabdeljlil: | Pan-Arab (Morocco) |

| Riadh Gouider: | Pan-Africa (Tunisia) |

| Surat Tanprawate: | Asia-Oceania (Thailand) |

| Tissa Wijeratne: | Asia-Oceania (Australia) |

| Wolfgang Grisold: | WFN Secretary General (WFN, U.K.) |