By Chandrashekhar Meshram

Chandrashekhar Meshram

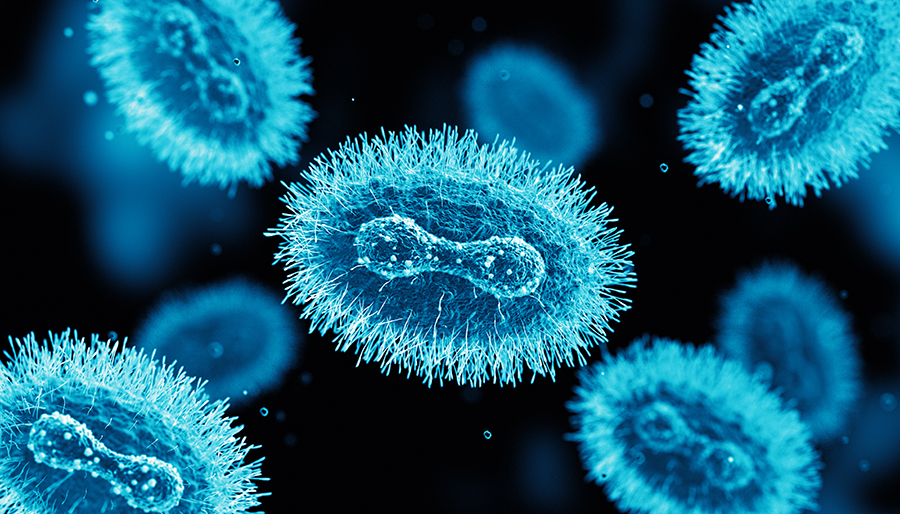

The World Health Organization recently declared monkeypox a global public health emergency of international concern. Monkeypox is a viral zoonosis caused by a double-stranded DNA virus in the Orthopoxvirus genus, transmitted to humans from animals—with symptoms similar to smallpox although clinically less severe. Details about the disease are available on WHO’s website.1

Since early May 2022, cases of monkeypox have been reported in countries where the disease is not endemic and continue to be reported in several endemic countries. Most confirmed cases with travel history reported travel to countries in Europe and North America, rather than West or Central Africa, where the monkeypox virus is endemic. This is the first time that many monkeypox cases and clusters have been reported concurrently in non-endemic and endemic countries in widely disparate geographical areas.2 As of Aug. 8, 30,189 cases have been reported from 88 countries, out of which 29,844 cases are from countries that have not historically reported monkeypox3.

Most reported cases so far have been identified through sexual health or other health services in primary and secondary health care facilities and have involved mainly, but not exclusively, men who have sex with men.

Human infection with monkeypox virus was initially identified in 1970, with almost all subsequent cases confined to rainforest regions of central and west Africa. In Africa, human case fatality rates from monkeypox infection are approximately 10%, and nearly half of infected individuals develop severe complications. In recent times, case fatality rate is around 3% to 6%1.

In the summer of 2003, there was an outbreak of monkeypox virus infection in 72 individuals (34 confirmed cases) in the midwestern United States, the first human infections reported from outside the African continent5. Fifteen percent of the confirmed cases were seriously ill, including one patient with severe encephalitis.

The most common symptoms included rash, fever, chills and/or rigors, adenopathy, headache, myalgia, sweats, and cough. Rash, predominantly centrifugal involving palms and soles, follows the viral-like prodrome after one to three days.

Neurological manifestations in the form of headache and malaise are observed in more than 50% of patients, while more serious complications like encephalitis and seizures are seen in less than 3% of patients.6 Anxiety and depression are common in hospitalized patients. Two cases of encephalitis due to monkeypox, both in girls requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation, are reported in the literature during past outbreaks7.

Neurological manifestations in the form of headache and malaise are observed in more than 50% of patients, while more serious complications like encephalitis and seizures are seen in less than 3% of patients.6 Anxiety and depression are common in hospitalized patients. Two cases of encephalitis due to monkeypox, both in girls requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation, are reported in the literature during past outbreaks7.

The U.S. patient with monkeypox encephalitis was a 6-year-old girl who initially presented with fever, pharyngitis, anorexia, malaise, and headache and was noted to have adenopathy and a vesiculopapular rash. She subsequently became somnolent and unresponsive and developed presumed seizure activity. Her MRI brain, EEG, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed abnormalities. Diagnosis was confirmed by detection of monkeypox virus IgG and IgM in serum and IgM in CSF and by positive culture, immunohistochemical, and PCR results on skin lesion material. The patient gradually improved over several weeks, eventually recovering fully8,4. The other was a 3-year-old girl who died on day 2 of hospitalization but CSF diagnostics were not performed7.

Because IgM does not generally cross the blood-brain barrier, the presence of IgM in CSF indicates active central nervous system infection with intrathecal antibody production. The absence of demyelination, cytotoxic changes caused by diffuse and focal edema, and intrathecal antibodies (IgM) all point to monkeypox as a possible cause of acute encephalitis7.

Monkeypox appears to have a fatal course almost exclusively in infants and young children, specifically those who have not received vaccination against smallpox.

These are early days, and we may find more cases with neurological involvement in the coming weeks or months. Any person with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and altered sensorium should be suspected as a case of monkeypox encephalitis. •

Chandrashekhar Meshram is co-opted trustee of the WFN.

References and further reading

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/monkeypox-oubreak-2022

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html

- Tyler KL emerging viral infections of central nervous system part 2. Arch Neurol 2009:66(9):1065-1074.

- Reed KDMelski JWGraham MB et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western hemisphere. N Engl J Med 2004;350 (4) 342- 350

- James B Badenoch, Isabella Conti, Emma R Rengasamy, Cameron J Watson, Matt Butler, Zain Hussain, Alasdair G Rooney, Michael S Zandi, Glyn Lewis, Anthony S David, Catherine F Houlihan, Ava Easton, Benedict D Michael, Krutika Kuppalli, Timothy R Nicholson, Thomas A Pollak , Jonathan P Roger Neurological and psychiatric presentations associated with human monkeypox virus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.03.22277069

- Caleb RS McEntire, Kun-Wei Song, Robert P McInnis, John Y Rhee, Michael Young, Erica Williams, Leah L Wibecan, Neal Noha, Amanda M Nagy, Jeffrey Gluckstein, Shibani S Mukerji and Farrah J Matin Neurologic Manifestations of the World Health Organization’s List of Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases Front. Neurol., 22nd February 2021 Sec. Neuroinfectious Diseases https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.634827

- Sejvar JJ, Chowdary Y, Schomogyi M, et al. Human monkeypox infection: a family cluster in the Midwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(10):1833-1840.

- Shafaati M, Zandi M. Monkeypox virus neurological manifestations in comparison to other orthopoxviruses Travel Medicine and infectious diseases Volume 49, September October 2022, 102414