Partnerships could lead to new treatments and improved patient care.

Christina Briscoe Abath, MD, EdM, and Keryma Acevedo, MD

Keryma Acevedo, MD

Christina Briscoe Abath, MD, EdM

Although it has gone by many other names, infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS) has been described since 1841. It is the most common infantile-onset epilepsy syndrome, and first-line treatments are over 40 years old. Steroids (prednisolone or ACTH) have been used since the 1950s, and vigabatrin has been used since the 1980s. The newest effective treatment for some children, epilepsy surgery, has been prescribed for epileptic spasms since 1990.1 There has been consensus about the initial treatment for over a decade, as well as recognition that the lead time to standard treatment affects long-term developmental outcomes.2,3 Treatment initiation of first-line therapy is considered a priority for the clinical team.

Despite this, most children in the world continue to have long delays in diagnosis. Although present in most settings, these delays are not equally distributed. In a large series from Bangladesh, the median lead time to a standard therapy was 5 months.4 Even in Boston (U.S.), the average lead time to standard therapy was 29 days.5 In the U.S., BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) infants, and those whose caregivers speak another language, are more likely to have delays to neurology referral.6,7

Just as disturbing, not all children who are correctly diagnosed will receive appropriate treatment despite consensus about standard therapies. At quaternary care centers in the U.S. with pediatric epileptologists, Black/Non-Hispanic children and those with public insurance are less likely to receive a standard treatment course.8

In many countries, standard therapies are not always readily available. In Chile, for example — despite access to pediatric neurologists and similar delays to diagnosis as in Boston — challenges with access to standard treatments in the public system mean that between 2015-2022, only 67% of children received a standard treatment course.5 Moreover, anti-seizure medications (ASMs) for IESS are not covered by the National Epilepsy Plan, resulting in an extremely heavy economical overload for families.9,10

On top of these issues, ACTH and vigabatrin have not been consistently available, and prednisolone has not been incorporated in the country’s list of approved drugs. This means that prednisolone is not available for purchase in Chile, resulting in families needing to go to Perú or other countries to buy the medication if indicated by their clinical team.11 Efforts are underway to address these challenges with the Ministry of Health.

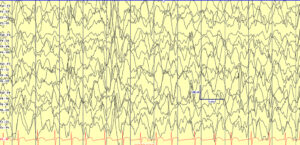

Hypsarrhythmia, initially described by Gibbs and Gibbs in 1952 (spelled as hypsarhythmia), is the classical interictal background pattern found in children with infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS). It is high voltage, chaotic, and has embedded multifocal epileptiform abnormalities. Hypsarrhythmia may be state dependent, and only present in sleep. While no longer required for IESS diagnosis, when present it can suggest a diagnosis when accompanied by history concerning for epileptic spasms in children of the appropriate age (1-24 months).

Partnering Together for Solutions

New therapies and research to understand mechanisms of disease for IESS are certainly needed, since only around half of children will respond to the first standard therapy and only around 70% will respond to early sequential or dual therapy.12,13 For this, significant increases in research for pediatric epilepsy are needed, given significant disparities in funding.14 The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) spent approximately $68 per person with epilepsy in 2023 ($232 million for 3.4 million individuals in the U.S.).15,16 In contrast, ALS receives $9,512 per person, Alzheimer’s $583 per person, and Parkinson’s disease $270 per person.16 Inadequate funding for drug research and development may be one reason why there have been no new first-line medications approved for IESS since the 1980s.

However, the percentage of children who do respond means that most children will still benefit from what we currently know and can apply appropriately.13 Given the high morbidity and mortality of IESS — with a 5-10% chance of response to a non-standard therapy — standard therapies are most likely cost-effective for public systems. Research should be done to support this supposition. We do know that epilepsy surgery is cost-effective for epilepsy, though cost-effectiveness specifically for epileptic spasm surgery has not been specifically assessed to our knowledge.17,18

Intervention is needed at every level of health systems to effectively address these gaps in diagnosis and therapy. In May 2022, the Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and Other Neurological Disorders (IGAP) was unanimously approved at the 75th World Health Assembly, providing an invaluable tool to advocate for treatment and access around the world.19,20

Joint efforts are needed to improve the standard of care for IESS, including early diagnosis, training general practitioners and pediatricians about adequate referral for suspicious clinical events, education of parents of children at high risk for IESS (Down Syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis, Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy), and access to standard treatments.

Families of children who have been affected by IESS are uniquely motivated to address these challenges. Partnering with these families to advocate for awareness and access to therapies is also needed. At a micro level, social media campaigns can promote epileptic spasm awareness. At the middle level, medical and other professional schools should incorporate pediatric epilepsy education (more common than other conditions that receive more attention). At a macro level, health systems should prioritize access to cost-effective epilepsy medication and therapies (including epilepsy surgery).

Much remains to be done around the world. In the U.S., one of the authors (CB) has been fortunate to start to work with the Infantile Spasms Action Network, parents of children with IESS, and other neurologists who are passionate about closing the equity gaps. We have created a module for primary care providers to recognize epileptic spasms and are working on a series of grassroots initiatives (a children’s book and a stuffed bear with EEG electrodes) to promote pediatric epilepsy awareness in Spanish, French, and English.

In Chile, the Chilean League Against Epilepsy (LICHE) is a non-profit organization that has several pharmacies distributed around the country that not only provide social benefits and discounts in ASMs, but also act as an intermediary to import medications to collaborate in the management of epilepsies, partnering with patients and their neurologists. As a PAHO/WHO Collaborating Centre, LICHE is committed with advocacy and education for patients, their families, caregivers and the community.

We believe collaboration, funding, and advocacy will be essential to making progress for children with IESS around the world. Please reach out to us with ideas, comments, and questions at: christina.briscoeabath@childrens.harvard.edu and kacevedo@uc.cl. •

Christina Briscoe Abath, MD, EdM, is incoming instructor of neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital. Keryma Acevedo, MD, is associate professor, Section of Neurology, Division of Pediatrics, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, and president of the Chilean League Against Epilepsy

References

1. Chugani HT, Shewmon DA, Shields WD, et al. Surgery for Intractable Infantile Spasms: Neuroimaging Perspectives. Epilepsia. 1993;34(4):764-771. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00459.

2. O’Callaghan FJK, Lux AL, Darke K, et al. The effect of lead time to treatment and of age of onset on developmental outcome at 4 years in infantile spasms: Evidence from the United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study. Epilepsia. 2011;52(7):1359-1364. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03127.

3. Pellock JM, Hrachovy R, Shinnar S, et al. Infantile spasms: A U.S. consensus report. Epilepsia. 2010;51(10):2175-2189. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02657.

4. Abath CB, Chandra Saha N, Hoque SA, et al. Clinical characteristics of children with infantile epileptic spasms syndrome from a tertiary-care hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e14323. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14323.

5. Briscoe Abath C, Vega S, Castro Villablanca F, Moya J, Garrido C, Hadjinicolaou A, Marin J, Munoz C, Soto C, Quintanilla C, Singh A, Margarit C, Andrade L, Leal L, Santana Almansa A, Gupta N, Acevedo K, Harini C. Proyecto Recaida: multi-center collaboration for infantile epileptic spasms syndrome relapse prediction and prognosis. American Epilepsy Society Conference 2023. Published December 2023. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://aesnet.org/abstractslisting/proyecto-recaida-multi-center-collaboration-for-infantile-epileptic-spasms-syndrome-relapse-prediction-and-prognosis.

6. Hussain SA, Lay J, Cheng E, Weng J, Sankar R, Baca CB. Recognition of Infantile Spasms Is Often Delayed: The ASSIST Study. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2017;190:215-221.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.009.

7. Briscoe Abath C, Gupta N, Hadjinicolaou A, et al. Delays to Care in Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome: racial and ethnic inequities. Epilepsia. n/a(n/a). doi:10.1111/epi.17827.

8. Baumer FM, Mytinger JR, Neville K, et al. Inequities in Therapy for Infantile Spasms: A Call to Action. Annals of Neurology. 2022;92(1):32-44. doi:10.1002/ana.26363.

9. Jr JE. Seizures and Epilepsy. OUP USA; 2013.

10. Engel J. What can we do for people with drug-resistant epilepsy?: The 2016 Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology. 2016;87(23):2483-2489. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003407.

11. Ramani PK, Briscoe Abath C, Donatelli S, et al. Initial combination versus early sequential standard therapies for Infantile Epileptic Spasms Syndrome-Feedback from stakeholders. Epilepsia Open. 2024;9(2):819-822. doi:10.1002/epi4.12895.

12. Knupp KG, Leister E, Coryell J, et al. Response to second treatment after initial failed treatment in a multicenter prospective infantile spasms cohort. Epilepsia. 2016;57(11):1834-1842. doi:10.1111/epi.13557.

13. Mytinger JR, Parker W, Rust SW, et al. Prioritizing Hormone Therapy Over Vigabatrin as the First Treatment for Infantile Spasms. Neurology. 2022;99(19):e2171-e2180. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201113.

14. Meador KJ, French J, Loring DW, Pennell PB. Disparities in NIH funding for epilepsy research. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1305-1307. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230a18f.

15. Epilepsy Data and Statistics | CDC. Published March 30, 2023. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/epilepsy/data/index.html.

16. RePORT. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/.

17. Widjaja E, Li B, Schinkel CD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pediatric epilepsy surgery compared to medical treatment in children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2011;94(1):61-68. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.005.

18. Ngan Kee N, Foster E, Marquina C, et al. Systematic Review of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis for Surgical and Neurostimulation Treatments for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy in Adults. Neurology. 2023;100(18):e1866-e1877. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000207137.

19. Grisold W, Freedman M, Gouider R, et al. The Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP): A unique opportunity for neurology across the globe. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2023;449. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2023.120645.

20. Wilmshurst JM. ICNA and the Global Regional Initiative Program: Aligning with IGAP towards providing child neurology services where they are most needed. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. n/a(n/a). doi:10.1111/dmcn.15836.