By Aaron Berkowitz, MD, PhD

When I first began working in Haiti with the nongovernmental organization Partners In Health (PIH) and its Haitian sister organization Zanmi Lasante (ZL) in 2012, I was asked to provide CME in neurology for internists, family physicians, and residents in several hospitals. There is only one neurologist in Haiti for 10 million citizens and no neurology training programs. Therefore, physicians training in Haiti have no opportunity to learn about neurologic disease from a neurologist – no preclinical course, no rotation, no CME. And yet, since the majority of patients in Haiti do not have access to the country’s only neurologist, they see these same general practitioners who have had no access to neurology education.

Aaron Berkowitz, MD, PHD

I began providing week-long CME courses on neurologic diagnosis and management of common neurologic conditions, and precepting local physicians in the care of their patients with neurologic disease between lectures. Our colleagues in Haiti appreciated the courses, and I enjoyed the opportunity to think through challenges in neurologic care and education in resource-limited settings (e.g., should a patient with an acute stroke and no access to CT receive aspirin?).1,2 However, the approach felt diffuse since I was giving lectures for large groups of practitioners at several hospitals, and seeing individual patients with multiple individual providers in different departments at each hospital. After several years, my colleagues in Haiti and I thought we could have a larger and more sustainable impact by focusing on a smaller group.

We decided to start a neurology rotation for the internal medicine residents at a newly opened teaching hospital in rural Haiti, Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais (HUM).3 Instead of lecturing in various hospitals and seeing patients with providers in different departments of each hospital, during each trip I worked with the same five PGY-2 internal medicine residents, and they worked only with me. The volume of consults we saw and the incredible progress in neurologic diagnosis and treatment made by the residents inspired us to start the first neurology training program in Haiti at HUM in 2015.

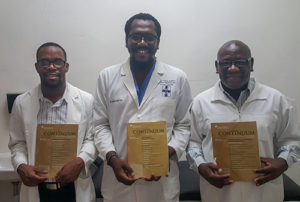

Three generations of neurology trainees at Hôpital Universitaire de Mirebalais in Haiti with issues of Continuum provided by the AAN-WFN Continuum Education Program. From left to right: Dr. Brégenet Lamour, Dr. Ronald St. Jean, and Dr. Roosevelt François.

We initiated a 2-year fellowship program that accommodates one trainee each year. Applicants must be graduates of internal medicine or family medicine residencies in Haiti. A team of about a dozen U.S.-based neurology faculty spend one to 12 weeks per year in Haiti providing bedside and classroom teaching, precepting the fellows in their care of inpatients and outpatients, and mentoring them to provide CME to their colleagues in other departments and conduct research projects.4

I have always encouraged our visiting faculty to bring a few textbooks in their suitcase for the neurology program’s growing library. One faculty member brought several issues of Continuum. Our fellows loved it:

“I was impressed with the teaching method in Continuum to create such a comprehensive resource on each topic and convey the material so clearly,” said Dr. Roosevelt François, the program’s first graduate (in 2017) and current in-country program director.

“I appreciate how each issue begins with the basics and arrives at the most up-to-date aspects of diagnosis and treatment,” said Dr. Brégenet Lamour, our current second-year fellow and soon-to-be second graduate.

I wanted to subscribe our neurology fellows in Haiti to Continuum, but I had not had good luck mailing things to Haiti; a book donation to a Haitian medical library from a U.S. publisher we had organized was held up in Customs for nearly six months. I learned about the AAN-WFN Continuum Education Program to assist in neurologic education in low-income countries (Haiti ranks 216 out of 235 countries in GDP per capita5). The coordinators of the program kindly agreed to send the journals to me in the U.S. to transport them in my suitcase to make sure they would arrive expeditiously. Five copies of each issue are provided; we keep one in our library, give one to our first graduate/faculty member, and provide one each to our two fellows. We save one for our next fellow. The fellows use Continuum not only for their own education but as a teaching tool.

Some of my U.S.-based colleagues ask if Continuum is too geared toward high-income settings to be applicable in Haiti, given that there is limited access to many neurodiagnostic tests and modern neurologic treatments in Haiti as in most low-income settings.6

“We don’t think ‘just because we don’t have this in Haiti, we don’t need to know about it.’ No!” Said Dr. Francois. “We need to know the most comprehensive up-to-date information to be prepared for the future when this technology arrives in Haiti.”

“While we await advances in technological resources, we must continue to train our human resources, said Dr. Ronald St. Jean, our current first year trainee. “Neurology existed long before technology.”

“Some of our patients want to travel abroad for diagnostic testing or treatment not available in Haiti, so we need to know how to advise them – is the test or procedure indicated? What are the risks and benefits of the intervention? Otherwise they could waste their time and money,” added Dr. Lamour.

The AAN-WFN Continuum Education Program provides an excellent resource for practitioners in low-income settings who may have limited access to internet in the field to provide up-to-date information on neurologic disorders. In the words of my colleague Dr. Francois, the first neurologist to be trained in Haiti:

“Thank you to my professors for helping me to discover Continuum, this inexhaustible resource of neurologic information, and thank you to the AAN-WFN for providing us with this resource. Continuum offers an enormous opportunity to continue my neurologic education with the most up-to-date information, and make sure my practice is current. Continuum is a crucial part of the continuity of my neurologic education.” – Dr. Francois •

References

- Berkowitz AL, Westover MB, Bianchi MT, Chou SH. Aspirin for acute stroke of unknown etiology in resource-limited settings: a decision analysis. Neurology. 2014 Aug 26; 83(9):787-93

- Berkowitz AL. Managing acute stroke in low-resource settings. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Jul 01; 94(7):554-6.

- Berkowitz AL, Martineau L, Morse ME, Israel K. Development of a neurology rotation for internal medicine residents in Haiti. J Neurol Sci. 2016 Jan 15; 360:158-60

- Israel K, Strander S, Martineau L, Pierre S, Morse ME, Berkowitz AL. Development of a neurology training program in Haiti. Submitted

- The World Bank. GDP per capita 2017 (US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?year_high_desc=true Accessed July 5, 2018

- McLane HC, Berkowitz AL, Patenaude BN, McKenzie ED, Wolper E, Wahlster S, Fink G, Mateen FJ. Availability, accessibility, and affordability of neurodiagnostic tests in 37 countries. Neurology. 2015 Nov 03; 85(18):1614-2

Aaron Berkowitz, MD, PhD, is the director of the global neurology program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School.