By Bo Norrving, MD, Didier Leys, Michael Brainin and Steve Davis

By Bo Norrving, MD, Didier Leys, Michael Brainin and Steve Davis

Health classifications are a core responsibility of the World Health Organization (WHO), assigned by international treaty with 193 member countries. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is the oldest and historically most important. Member countries are required to report health statistics to WHO according to ICD, and ICD categories also are used as the basis for eligibility and payment for health care, social and disability benefits and services. ICD should have broad global utility, not only for specialists or neurologists, but for all physicians and health workers. All global regions are represented on WHO advisory groups, with a good representation of low- and middle-income countries.

ICD-10 was completed in 1990; the interval to ICD-11 is the longest time without revision in history of the ICD. The period has seen major advances in our understanding of cerebrovascular diseases and their treatment. The ICD-11 is mandated by the World Health Assembly and is expected to be officially approved by the 2015 World Health Assembly. A novel feature of ICD-11 is the inclusion of definitions. At WHO, the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Department is responsible for the revision of Diseases of the Nervous System. The Neurology Topic Advisory Group is chaired by Raad Shakir, and has seven individual members and more than 10 representatives from neurology associations and federations.

The World Stroke Organization (WSO) has been involved in the ICD-11 revision at WHO since 2010 and has been invited in this function as the NGO in official relations with WHO regarding stroke. The Cerebrovascular Disease ICD-11 advisory group is chaired by Bo Norrving, Sweden, with members Valery Feigin, New Zealand; Padma Gunarathne, Sri Lanka; Vladimir Hachinski, Canada; Michael Hennerici, Germany; Ming Liu, China; Peter Rothwell, UK; and Jeffrey Saver, US.

In the ICD-11, all cerebrovascular diagnoses will for the first time form one single block within Diseases of the Nervous System, which represents a major change in the classification. The work of the ICD-11 cerebrovascular working group has been reviewed by the board of the WSO and has been openly available to public comments. The document has been submitted to WHO, and the next steps include international scientific peer review of the whole ICD-11 and field trials. The aim is that the ICD-11 in its complete form is submitted to the 2015 World Health Assembly, for subsequent implementation in member countries.

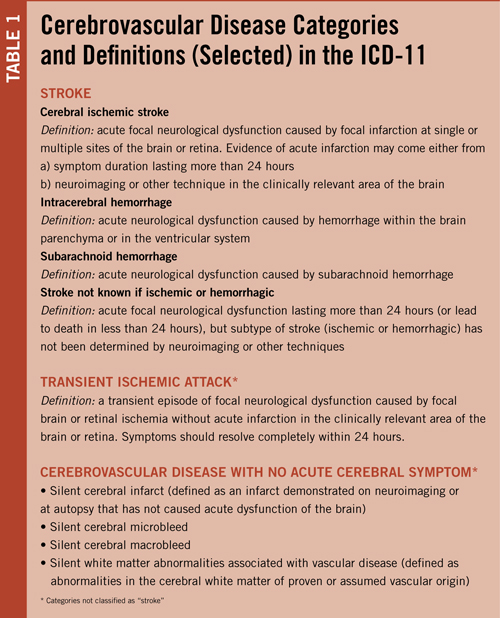

Selected key categories of the ICD-11 and their definitions are summarized in Table 1. The term “stroke” requires the presence of acute neurological dysfunction, which is in line with the definitions generally used in previous epidemiological studies, official statistics and the Global Burden of Disease project. This requirement was felt to be of particular importance in low- and middle-income countries in which a large proportion of cases will be diagnosed based only on clinical features without the addition of neuroimaging. Keeping the requirement of acute neurological dysfunction for stroke will allow comparison of data between regions and between time periods for the study of trends, which are extremely important for monitoring of global burden of diseases.

The ICD-11 cerebrovascular section includes a new cause category: “Cerebrovascular disease with no acute cerebral symptoms” which includes silent cerebral infarcts, silent cerebral microbleeds and silent white matter abnormalities associated with vascular disease.

“Silent cerebral infarct” is defined as an infarct demonstrated on neuroimaging or at autopsy that has not caused acute dysfunction of the brain. There is substantial scientific support that silent cerebral infarcts carry important consequences on brain function (cognition, gait, balance function) and prognosis. Whereas effects of specific therapies have not been demonstrated yet, risk factor assessment and control should usually be applied for preventive purposes. However, the risk of disease stigmatization also was carefully considered, and it is specifically stated that these entities do not represent a “stroke,” a distinction that may have unwanted consequences from legal or insurance perspectives.

More than 90 percent of all cerebrovascular lesions in the brain are not associated with acute neurological dysfunction; in the general elderly population the prevalence of silent cerebral infarcts and microbleeds range from one-fifth to one-half with increasing age. Use of different stroke definitions that do, or do not, include silent cerebral infarcts and microbleeds, carry a potential risk of miscoding that may seriously distort official statistics and of causing confusion within the health sector and to the general public.

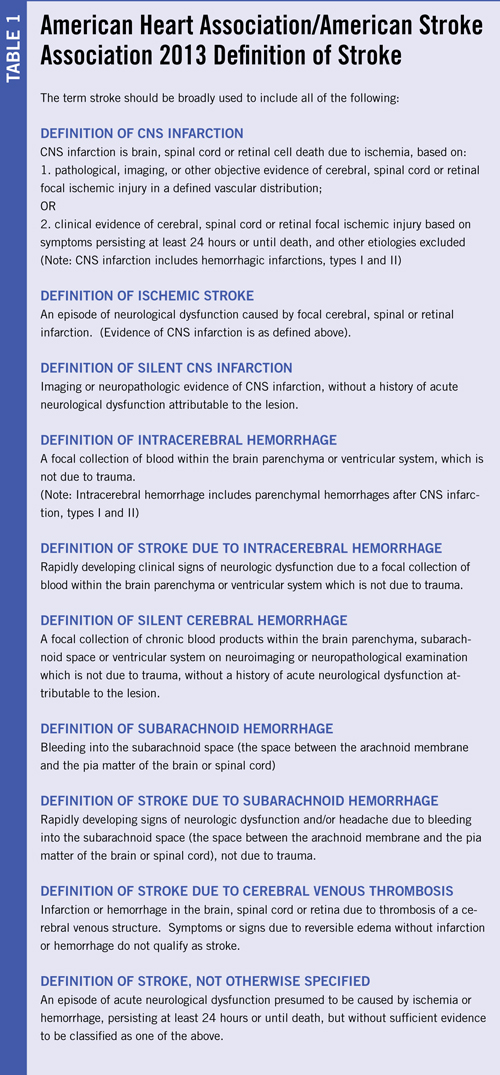

As the current WSO president, Norrving was invited to the AHA/ASA working group, but when it became apparent that the group would arrive at a definition of stroke that was importantly different from the one in ICD-11 (basically the inclusion of silent cerebral infarction and silent cerebral hemorrhage within the lexicon of stroke), the issue was discussed within the organization and the decision was taken that WSO needed to withdraw.

WSO cannot officially approve another definition of stroke than the one developed within the governmental framework of the ICD-11 at WHO. Similarly, Didier Leys, as the current ESO president, was also invited to the AHA/ASA working group; ESO took the decision also to withdraw as the organization supported the definition of stroke as defined in the ICD-11, and also argued that definitions on cerebrovascular disease should be taken on a world, rather than a regional, level.

For the future, it is essential that transparent definitions are used that facilitate reporting and comparisons on a global scale. Stroke is one of the prioritized non-communicable diseases within the WHO Global Action Plan for NCDs 2013 to 2020, and the prevention and management of stroke requires the full support of all actors involved, including the stroke and neurological societies.

Norrving is immediate past president WSO and chair of the ICD-11 Cerebrovascular Advisory Group. Leys is immediate past president ESO. Brainin is ESO president. Davis is WSO president.

Prof. Raad Shakir has been a prominent figure in neurology in the United Kingdom for more than 20 years and was one of the key persons in the organization of the successful London 2001 World Congress of Neurology. His contributions to both neurology in the U.K. and to the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) have been witnessed by many.

Prof. Raad Shakir has been a prominent figure in neurology in the United Kingdom for more than 20 years and was one of the key persons in the organization of the successful London 2001 World Congress of Neurology. His contributions to both neurology in the U.K. and to the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) have been witnessed by many.