By Vladislav Voitenkov, MD, PhD

Dr. Voitenkov during EMG symposium

The large scientific meeting, Clinical Neurophysiology and Neurophysiology, was held by the Scientific Research Institute of Children’s Infections in St. Petersburg, Russia, November 26-27, 2015. Held at the Mosckovskye Vorota Congress Center in St. Petersburg, the event attracted 395 participants.

The scientific program was dedicated to general problems of neurophysiology in Russia, Commonwealth of Independent States countries and the European Union, and to certain methods in neurophysiology and neurorehabilitation. The congress hosted plenary lectures and 10 symposiums in all. Plenary lectures included such themes as modern aspects of meningitis and encephalitis treatment and diagnosis in pediatrics, presented by Professor N. Skripchenko of the Scientific Research Institute of Children’s Infections, recent discoveries in the field of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), including TMS-MRI fusion techniques, presented by Dr. B. Neggers, University Medical Center Utrecht Brain Center, the Netherlands, and the role and place of electrophysiology in modern medicine, presented by Professor L. Sumsky, Neurology Center, Moscow.

Dr. Neggers during TMS-MRI fusion workshop

Symposia themes were vast and issues included scientific and clinical aspects of electromyography, electroencephalography, neurorehabilitation, ultrasonography of the brain, muscles and peripheral nerves, neuro-orthopedics, electrophysiology and audiology, neurorehabilitation and nurses’ education. Special interest was dedicated to the TMS symposium, which gathered more than 100 participants and 12 speakers, including Professor J. Mally of the Institute for Neurorehabilitation in Sopron, Hungary. He presented material on TMS as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. Professor N. Nazarenko of the Diagnostic Center for Altay Region, Barnaul, Russia presented data on TMS investigation in tick-borne encephalitis and many others.

The previous congress, which took place in 2015 was dedicated to more general topics and had a more classic design. This year’s event was more inclusive of the newest techniques, approaches and more advanced methods.

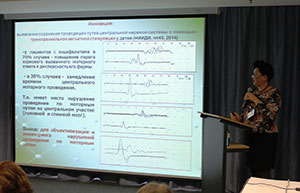

Professor Skripchenko on TMS findings in encephalitis in children

At the meeting, 126 speakers presented their data on the topics. Symposia included talks from leading Russian and international speakers, as well as presentations from early career researchers whose material has had a significant impact in their fields. Delegates for the congress gathered from Russia, Ukraine, Belorussia, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and Hungary. Russian delegates came from more than 90 locations, including the Far East and Arctic Northern provinces of the country.

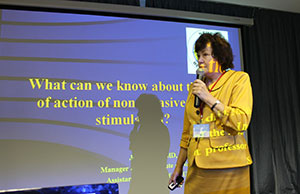

Professor Mally on non-invasive brain stimulation.

The meeting garnered positive and warm feedback from the delegates and speakers. The organizing committee is now deep into the planning of the next event, which will take place in St. Petersburg at the end of November 2016.

The validity of the examination needs the input of the scientific experts at the European Academy of Neurology. The reliability of the outcome depends on the number and quality of the participating candidates. A statistical evaluation to eliminate “bad questions” only can be realized in a group of sufficient size. Establishing a passing score can be determined by specialists prior to the test. However, modification of such a score may be necessary after getting data from a sufficient number of adequate participants.

The validity of the examination needs the input of the scientific experts at the European Academy of Neurology. The reliability of the outcome depends on the number and quality of the participating candidates. A statistical evaluation to eliminate “bad questions” only can be realized in a group of sufficient size. Establishing a passing score can be determined by specialists prior to the test. However, modification of such a score may be necessary after getting data from a sufficient number of adequate participants.