By Dr. Rabwa Fadol

Many thanks to Dr. Lawrence Tucker and his team for organizing the online 2022 EEG course and to the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) for sponsoring me as a junior neurologist for such an outstanding course. It is so valuable, informative, and well organized.

I joined this course while I was in the last year of my MD neurology training in Sudan. My target in the course was to expand my knowledge about the basics of the EEG, its implications in diagnosing different neurological disorders as well as sleep disorders, as I worked in a sleep lab for a couple of years.

The course was well structured from the basic concepts up to the reporting of the EEG.

The display of information by different ways, such as lectures, videos, audios, interactive discussions (epochs) with nice comments from the EEG experts, and frequent assessments by end-of-module quizzes made the subject easier to understand and interesting. The time management for the different modules was excellent (suitable and flexible) enabling us to follow smoothly.

Thanks to God that I passed both the EEG exam as well as my MD neurology exam at the same time. And I hope to implement this knowledge in my practice and to teach the junior colleagues in order to improve our health care system.

I hope the WFN will offer more opportunities to more candidates in our country and other sub-Saharan countries to attend this course and other neurological studies to help us improve our care to the patients. •

Dr. Rabwa Fadol is a Sudanese neurologist.

The London office is keeping busy with our agendas. In addition to Laura, Jade, and Carlos, we have help from Yannik and, increasingly Chiu, with our expanding activities and website as well as social media. Kimberly Karlshoej, who served as the strategic and program director and has added much vigor and great ideas for the WFN, had to resign for personal reasons. We thank her for all of her work. We will implement a new structure of a voluntary project-based assistant, called an “internship,” which will help with our communication with the global societies such as the WHO and UN ECOSOC under the supervision of Alla Guekht and the London office.

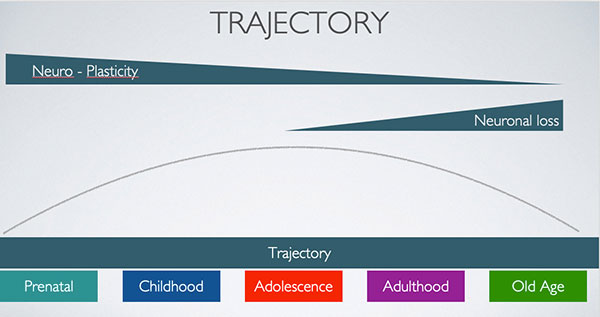

The London office is keeping busy with our agendas. In addition to Laura, Jade, and Carlos, we have help from Yannik and, increasingly Chiu, with our expanding activities and website as well as social media. Kimberly Karlshoej, who served as the strategic and program director and has added much vigor and great ideas for the WFN, had to resign for personal reasons. We thank her for all of her work. We will implement a new structure of a voluntary project-based assistant, called an “internship,” which will help with our communication with the global societies such as the WHO and UN ECOSOC under the supervision of Alla Guekht and the London office. One important aspect of our activities is brain health. Despite several definitions, interests, and a number of stakeholders, the concept of brain health is important, and also closely connected with the IGAP. I want to remind readers that the next WFN World Brain Day (WBD) bears the title “Brain Health and Disability,” and thus indicates that the WFN is following the route to support the brain health concept, which was initiated in 2020. Although brain health is a universal concept, it needs to be targeted from many perspectives. The function of a healthy brain in all developmental stages from the prenatal period into old age, as well as the close connection of brain function with mental disorders, are pragmatic directions for neurologists. These need to be supported by many initiatives as delineated in the IGAP and by the WHO paper on brain health.

One important aspect of our activities is brain health. Despite several definitions, interests, and a number of stakeholders, the concept of brain health is important, and also closely connected with the IGAP. I want to remind readers that the next WFN World Brain Day (WBD) bears the title “Brain Health and Disability,” and thus indicates that the WFN is following the route to support the brain health concept, which was initiated in 2020. Although brain health is a universal concept, it needs to be targeted from many perspectives. The function of a healthy brain in all developmental stages from the prenatal period into old age, as well as the close connection of brain function with mental disorders, are pragmatic directions for neurologists. These need to be supported by many initiatives as delineated in the IGAP and by the WHO paper on brain health. The 2023 topic of “Brain Health and Disability” also aligns with initiatives of the WHO. We are developing the WBD program jointly with the six WFN regions and have also invited the World Federation of Neurorehabilitation as a partner. This worldwide society has its focus on neurorehabilitation and promotes development and research.

The 2023 topic of “Brain Health and Disability” also aligns with initiatives of the WHO. We are developing the WBD program jointly with the six WFN regions and have also invited the World Federation of Neurorehabilitation as a partner. This worldwide society has its focus on neurorehabilitation and promotes development and research.