J. Eadie, Brisbane, Australia

M. J. Eadie

Over several centuries, those born in Scotland have often left their homeland because of the perceived lack of opportunity, and then made successful lives in other countries. This behavior was particularly frequent during the so-called Highland clearances of the 18th and 19th centuries. Scottish landowners dispossessed their tenant farmers who had been engaged in small-scale agriculture for generations, to make land available for more profitable sheep rearing. As one consequence, more people of Scottish ancestry now live elsewhere in the world than in Scotland itself. In 1956, there was a Highland clearance on a micro scale, when lack of available consultant positions in the British National Health Service resulted in a trained neurologist of Highlander origin emigrating to Australia.

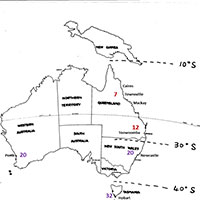

An outline map of Australia found among John Sutherland’s papers, with dotted latitude lines added to it in his hand. The map includes names of the cities where he studied multiple sclerosis prevalence, and the local prevalence figures per 100,000 of population he obtained, have subsequently been inserted; the figures from his earlier survey in red, and from the later one in purple.

John Sutherland (Fig 1) was born in Caithness, in the extreme northeast of mainland Scotland, in 1919. He was educated in Glasgow, and graduated in medicine from the University of Glasgow in 1943. After service in the wartime Royal Navy, he returned to the Western Infirmary, Glasgow, in 1946 as medical registrar to Douglas Adams, a consultant physician with neurological interests, particularly concerning multiple sclerosis. Adams launched Sutherland into clinical and laboratory research related to the disease, resulting in the addition of a research medical degree (Glasgow) to Sutherland’s existing basic medical qualifications. After his appointment in Glasgow ended, Sutherland went to Inverness, the so-called “capital” of the Scottish highlands, in 1950, as senior medical registrar. He remained there for five years, followed by some months in a similar level position in Aberdeen, a little further south on the east coast of Scotland. In Inverness, though without the formal title, he in effect functioned as neurological consultant for the Scottish Highlands, the Hebridean Islands off the northwest coast of the country, and the Orkney and Shetland Islands north of the mainland. From Inverness he investigated a suspicion that arose out of his multiple sclerosis clinical studies in Glasgow, namely that there might be an uneven distribution in the occurrence of multiple sclerosis between parts of Scotland.

Because of his close professional relationships with medical practitioners in the areas he serviced, he achieved a high multiple sclerosis case ascertainment rate and, after various field expeditions, found that the prevalence of the disease in the shaded areas of the map (Fig 2) covered over in red was approximately twice that in the remaining shaded parts. He realized that the red areas were those where the population was predominantly of Nordic origin, a later-day result of Viking invasions and settlement centuries earlier. The remaining shaded areas had populations largely of Gaelic lineage and who still could understand and employ the Gaelic language. Thus, he obtained persuasive evidence, perhaps the earliest, that genetic and racial factors might play a role in the etiology of multiple sclerosis.

John Sutherland’s map of Scotland. The shaded areas show where he investigated the prevalence of multiple sclerosis, with the original version modified by coloring over in red in the higher prevalence areas.

In the year that this study was published,1 Sutherland arrived in Australia to take up an academic position in Brisbane, the capital of the state of Queensland that occupies most of the northeast quarter of the continent (Fig 3). After a few years, he commenced consultant neurological practice in that city. In the 1950s, it was generally believed locally that multiple sclerosis rarely occurred in the northern half of Australia, and that native-born Queenslanders never suffered from it. Sutherland soon showed that these ideas resulted from a local medical unfamiliarity with the spectrum of clinical manifestations of the disorder, so that it simply was not being recognized.

Knowing that multiple sclerosis prevalence increased with increasing distance from the equator in the northern hemisphere, and because of his earlier investigation being alert to the possible relationship between geographical and racial factors and disease distribution, Sutherland proceeded to investigate whether a similar disease prevalence distribution in relation to latitude existed in the southern hemisphere. No adequate data were then available. Australia was a peculiarly suitable site for investigating the matter. It possessed a 3000 km -long north-to-south dimension, a uniform and high standard of medical practice throughout, main population centers spaced reasonably evenly along its eastern seaboard, and was populated almost exclusively by those of British and other European stock who spoke English (though some of them may have initially wondered if Sutherland also did, until his broad Scotch accent gradually became somewhat attenuated).

John Sutherland in his 60’s

Sutherland initially carried out a field study of multiple sclerosis prevalence in three tropical Queensland coastal cities (Cairns, Townsville, and Mackay) and in sub-tropical Toowoomba (about 100 km west of Brisbane).2 Recognized cases of the disease were found to have a lower prevalence in the tropical than in the sub-tropical population, though the disease prevalence was low relative to that in Northern hemisphere populations.

Spurred on by this finding, he then collaborated with local neurologists and epidemiologists in selected southern cities (Newcastle, Perth and Hobart) to show a higher multiple sclerosis prevalence the further south the matter was studied.3 Later still, in another collaborative study that took in New Zealand, overall closer to the South Pole than the southernmost parts of Australia, further evidence was obtained.4 Thus Sutherland’s name became associated with a series of investigations that demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt that multiple sclerosis prevalence increased with greater distance from the equator in the southern as well as in the northern hemisphere.

He also initiated other multiple sclerosis epidemiological investigations in Australia. One study showed that the prevalence of the disease correlated with the notifications of paralytic poliomyelitis in epidemics of that disease at different latitudes in Australia. This finding led to speculation that exposure to some unidentified organism, occurring earlier in childhood in hotter climates, while some residual immunity of maternal origin persisted, might have prevented later clinical disease. However, in cooler climates, exposure to the cause occurred later and resulted in overt disease.5 He also drew attention to a correlation between decreasing average annual sunlight exposure in regions of Australia and increasing multiple sclerosis prevalence,4 a finding largely forgotten until resurrected by recent interest in the relation between vitamin D and the disease. Additionally, he proposed a speculative hypothesis regarding multiple sclerosis prevalence and the capacity of regional soils to bind molybdenum in preference to copper.6

In Australia, Sutherland became a very successful consultant who developed an additional major interest in medico-legal neurology. With the years, his active investigative work into multiple sclerosis diminished, though he retained a watch on the relevant literature until the end, which came in 1995.

Scotland’s inability to provide appropriate professional opportunity for another of its many sons thus provided Australia with one of that country’s pioneer neuroepidemiologists, a man whose investigative endeavors helped awaken ongoing broader interest into multiple sclerosis far from his homeland.

References

- Sutherland JM (1956) Observations on the prevalence of multiple sclerosis in northern Scotland. Brain 79: 635-654.

- Sutherland JM, Tyrer JH, Eadie MJ, Casey JH, Kurland LT (1966) The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Queensland, Australia. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 42 (Suppl 19): 57-67.

- McCall MFG, Brereton TLG, Dawson A, Millingen K, Sutherland JM, Acheson ED (1968) Frequency of multiple sclerosis in three Australian cities – Perth, Newcastle and Hobart. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 31:1-9.

- Sutherland JM, Tyrer JH, Eadie MJ (1962) The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Australia. Brain; 85:149-164.

- Eadie MJ, Sutherland JM, Tyrer JH (1965) Multiple sclerosis and poliomyelitis in Australasia. British Medical Journal 1: 1471-1473.

- Layton W, Sutherland JM (1975) Geochemistry and multiple sclerosis: a hypothesis. Medical Journal of Australia. 1:73-77