By Peter J. Koehler

Nearly every neurologist will have experienced the satisfaction of diagnosing hypoglycemia with more or less severe neurological signs and curing the patient “on the needle” by the administration of glucose. However, few will have done so to treat hypoglycemia that was induced on purpose.

Somatic Treatments in Psychiatry

To understand this, we have to go back to the 1920s and 1930s when severe (neuro) psychiatric diseases were treated with extraordinary therapies. We already read about malaria fever therapy by Nobel laureate Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857-1940) in the 1920s to treat dementia paralytica (general paralysis of the insane or GPI; see Volume 35, Issue no. 4 of October/November 2020, pp. 5 and 10).

Up to that period, the somatic treatments of psychosis had mainly consisted of morphine, hyoscine, bedrest, and hydrotherapy. Sleep therapy became one of the first specific treatments.

At first, it was induced by bromides that had been used for the treatment of epilepsy since 18571, and after the turn of the century by barbiturates, as for instance applied by the Swiss psychiatrist Jakob Klaesi (1883-1980) at the Burghölzli asylum in Zurich in the early 1920s.

Manfred Sakel

Manfred Sakel (courtesy nlm_nlmuid-101427953-img)

As happens so often in medicine, a new drug was investigated for alternative indications. Insulin had been discovered in 1922, and soon after the Austrian-Jewish Manfred Sakel (1900-1957), who was working with Kurt Mendel (1874-1946; eponomist of the Mendel-Bekhterev reflex) at the Lichterfelde Sanatorium in Berlin, used low dosages in patients suffering from symptoms of morphine withdrawal (cold-turkey). In some patients, he had induced disorders of consciousness unintentionally—“entweder durch Überdosierung von Insulin oder unzureichende Nahrungsaufname seitens der Patienten”2 [either from overdosing of insulin or from inadequate food intake by the patient]—and found the desire for morphine and restlessness disappeared.

He published the findings in 1933, and the idea occurred that insulin coma might be effective for severe psychiatric disorders. Moving back to Vienna in that year, he worked at the university psychiatric clinic and presented a lecture at a meeting of the Medical Society of Vienna, “A new type of treatment for schizophrenics and patients with confused excitation.”3

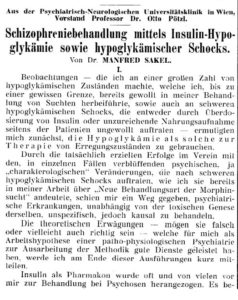

After persuading his chief, Wagner-Jauregg’s successor Otto Pötzl (1877-1962), Sakel started experimenting with the method in schizophrenic patients. The effects seemed to be quite impressive—“die Erfolge meiner Methodik [waren] geradezu erstaunlich und eindeutig” [the successes of my methodology (were) downright astonishing and clear]—and he now wished to publish on a larger number of patients in a series of 13 articles in 1934-1935. As occurs from the title “Schizophreniebehandlung mittels Insulin-Hypoglykämie sowie hypoglykämischer Shocks,” he distinguished “insulin-hypoglycemia” from “hypoglycemic shock.” The latter had been carefully prevented initially, but in his method for the treatment of schizophrenia this was “die wirksame Kardinalpunkte” [the effective cardinal point].

Four Phases

Sakel’s 1934 publication.

He started with increasing dosages of insulin intramuscularly every 4-4.5 hours. The patient’s symptoms and signs or the level of glucose and blood pressure / pulse determined the moment to provide glucose to end the hypoglycemic period. In phase two, the purpose was to achieve a severe hypoglycemic shock, which could be recognized either by profuse sweating or gradual increasing somnolence. The latter condition could be interrupted by psychotic excitement and would finally result in coma.

“In dieser Phase treten bereits pathologischen Reflexe auf. Pyramidenzeichen: Babinski, Oppenheim, Mendel-Bechterew. Bei längerem Zuwarten kann das Koma eine solche Tiefe erreichen, dass sämtliche Reflexe, erlöschen. Also völlige Areflexie mit völliger Atonie der gesamten Muskulatur“

[At this stage, pathological reflexes already appear. Pyramid signs: Babinski, Oppenheim, Mendel-Bechterew. If you wait a long time, the coma can reach such a depth that all reflexes are extinguished. So complete areflexia with complete atony of the entire musculature]. (For the Oppenheim and Mendel-Bechterew signs, I refer to the World Neurology issue of October 2010 “Foot eponyms leave their mark.)

If no complications occurred, bradycardia down to 34 / minute could be observed. More rarely, an epileptic seizure was seen, including tonic-clonic cramps, tongue bite, and “bad pulse.” “Sehr bedrohlich, cave!” [Very threatening, beware!]

The problem was that it was difficult to predict the patients’ reaction from the dosage of insulin. Phase three lasted one or several days, during which no or very little insulin was administered. Recovery and registration of the effect were the purposes of this phase.

Extensor plantar (Babinski) sign during ICT (still from the film).

Sometimes it was sufficient only to induce phase one, which did not always mean that the hypoglycemia had been less severe, as sometimes lower glucose levels were found than in patients, who had become deeply comatose.

If it was not necessary to return to phase two, the patient would enter phase four, “Stabilisierung und Ordnung des Zustandsbild.” Even in this phase, the patient received low doses of insulin three times a day. During the treatment, the patient would be checked regularly and several medications should be standby, including adrenaline, glucose solution with gastric tube, as well as lockjaw, “cardiaca und analeptica.” Therefore, the treatment took up much time of the nursing staff. Intravenous glucose was only used in acutely dangerous situations.

Following the series of papers in the Viennese journal, Sakel published a book in 1935: Neue Behandlungsmethode der Schizophrenie [A New Method of Treating Schizophrenia]. The reactions to Sakel’s new therapy were very positive. Although Sakel moved to New York in 1936, ICT had already been introduced in the United States by Joseph Wortis (1906-1995), who had graduated from the University of Vienna and trained in psychiatry at the Bellevue Hospital in New York, after he had seen Sakel at work in Vienna in 1934. He translated Sakel’s monograph into English4.

Early Trials

As for the mechanism of action, Sakel compared hypoglycemia to hypoxia and believed that certain nerve cells, responsible for the psychotic phenomena, would be damaged selectively. Although he claimed improvement in 88% and recovery in 70%, it was much debated afterward.

Kurt Kolle (1898-1975), neuropsychiatrist in Frankfurt and later professor of psychiatry in Munich, mentioned the figure of 45% of lasting full remissions, in comparison to only 10% of spontaneous improvement. The convulsions were believed to be the essential element and not the insulin or hypoglycemia.

Later comparisons with Electroconvulsive Treatment (ECT), developed by professor of neuropsychiatry in Rome Ugo Cerletti (1877-1963) in 1938, and leucotomy (a limited form of psychosurgery), were believed to show an advantage over insulin coma therapy (ICT), but opposite opinions were also seen. A randomly controlled trial of ICT and chlorpromazine, that became available for trials in 1952, demonstrated improved safety as well as effectiveness of the latter (1958)5. However, this did not stop the practice of ICT.

New Methods to Induce Convulsions

Preparing for sucrose solution administration by gastric tube to end the ICT (still taken from the film).

Around the first publications of ICT for schizophrenia, the Hungarian-Jewish neuropathologist and neuropsychiatrist Ladislas Meduna (1896-1964), working at Károly Schaffer’s (1864-1939) Brain Research Institute in Budapest, introduced a new chemically induced shock therapy that produced convulsions without coma. A report of the first 26 patients treated with camphor or metrazol was published in 1936. Meduna emigrated to the United States (Chicago) in 1939. In fact, this was the first convulsive therapy, as in ICT convulsions were not the purpose.

The safer ECT was applied for the first time in 1938 and would later take over the chemical methods. Severe depressions may still be an indication of ECT.

Filmlink: Insuline coma therapy demonstrating several patients. The film is accessible from the MedFilm teaching and research database at Metrazol, electric and insulin treatment of functional psychoses (1934) – Medfilm (unistra.fr). On the film, the various phases of ICT can be observed. Restlessness, coma, Babinski signs, myoclonus, and seizures are all shown. The hypoglycemia is stopped by sucrose solution via gastric tube. If this did not result in improvement soon enough or in case of a seizure intravenous glucose was applied. After the treatment the patients received a carbohydrate-rich meal.

MedFilm: is a collaborative initiative accommodated by the University of Strasbourg, France. They archive and thus preserve medical and other health-related films, TV programs, commercials, and internet videos ranging from the very late 19th century to the early 21st century. They do not just store them online. Describing the films, putting them in context, and analyzing them fuels their and others’ research in the fields of history of medicine, science, and media history.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Elisabeth Fuchs and Prof. Christian Bonah of the department of the history of life and health sciences of the University of Strasbourg, France. •

Literature

- Eadie MJ. Sir Charles Locock and potassium bromide. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:274-9.

- Sakel M. Schizophreniebehandlung mittels Insulin-Hypoglykämie sowie hypoglykämischer Schocks. Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift 1934; 84: 1211-4.

- Shorter E. Sakel versus Meduna: different strokes, different styles of scientific discovery. J ECT. 2009 25:12-4.

- Shorter E. A history of psychiatry. New York, Wiley, 1997, pp.207-214.

- Shorter E. A historical dictionary of psychiatry. Oxford, University Press, 2005, pp. 142-4.