By Rohit Bhatia, MD, DM, DNB

The stroke epidemic has arrived in India. While we were busy combating the scourge of infections and deficiency diseases, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including stroke stealthily crept up on us.

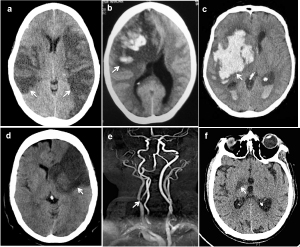

With a population of 1.2 billion today and growing, India finds itself staring at a stroke epidemic (See “The Stroke Fact Sheet in India.” on page 8.) 1,2. In addition to strokes due to conventional risk factors, cardio-embolic stroke due to rheumatic valvular heart disease, cerebral venous thrombosis, and strokes related to tuberculous meningitis still remain important causes of stroke, especially in the young Indian population. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Types of strokes (arrows): (a) bilateral arterial infarcts in a patient with rheumatic heart disease and atrial fibrillation (b) venous infarct in a post-partum patient with superior sagittal sinus thrombosis (c) intracerebral hemorrhage in a hypertensive patient, (d) arterial embolic infarction due to large artery athersoclerosis and carotid stenosis (e) and (f) perforator artery infarction in patient with tubercular meningitis.

The recently published Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study from 18 low-, middle- and high-income countries showed that incidence of major cardiovascular disease was highest in low-income countries, despite the fact that these countries had the lowest risk-factor burden3.

Challenges in stroke care include a limited number of trained neurologists who are mostly urban, a large number of patients who are mostly rural, a lack of knowledge and awareness both about stroke risk factors and treatment in the general public and prohibitive cost of stroke care. There is a lack of uniformity and standardization of secondary and tertiary stroke care while availability of primary care in stroke is extremely unreliable. The stroke epidemic did catch us by surprise and in an unprepared state, but the situation is gradually beginning to improve and we are optimistic about the future. (See Figure 2.)

Acute stroke care has barriers, including recognition, pre-hospital delays, physician expertise, lack of ambulance services, cost of tPA and lack of critical care facilities. Although thrombolysis (using tPA) continues to be available only in urban private or academic hospitals, there has been a recent rise in the number of stroke patients getting the benefit of this treatment.

Figure 2. Recovering stroke patients at the Stroke Clinic, Neurosciences Center, AIIMS.

In the year 2009, 1,648 patients were thrombolysed, while in 2011, the number rose to 2,975 and a center in northwest India reported a four-fold increase in rates of thrombolysis2. About 100 centers in India currently have facilities to provide intravenous thrombolysis, and the numbers are likely to rise with awareness and experience.

In the national capital region, the cost barrier is gradually being offset for eligible patients by the provision of free tPA by the government in state-run academic hospitals, including All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. The National Program on Prevention and Control of Cardiovascular Diseases, Diabetes and Stroke4 (NPCDCS) launched in 2008 by the ministry of health and family welfare (See “Major Components of NPCDCS.”) addresses NCD prevention by risk reduction, early diagnosis and appropriate management through health promotion programs for the general population and high-risk groups.

Figure 3. Map of India showing the National Program on Prevention and Control of Cardiovascular Diseases, Diabetes and Stroke (NPCDCS Program), Government of India. Red dots indicate places where it is currently implemented. Stars indicate the Indian states4.

At present, the NPCDCS program is implemented in 100 districts across 21 Indian states, and it is expected to be rolled out in 640 districts by 2017 under the 12th five-year plan. (See Figure 3.) Developing and running dedicated stroke units in the face of the extremely limited health resources is a challenge; 35-40 stroke units currently exist, mainly in bigger cities and more often in private hospitals.

Improving Access to Stroke Care

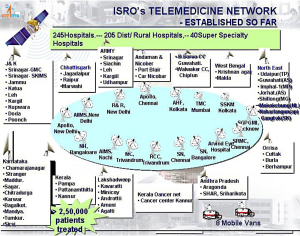

Reaching out to remotely located patients remains difficult, and telestroke is recognized as a potential solution5. Telemedicine has been successfully used by the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) to meet the needs of remote Indian hospitals6.

The telemedicine network implemented by ISRO in 2001 presently stretches to around 100 hospital countrywide, with 78 remote rural/district health centers connected to 22 speciality hospitals in major cities, thus providing treatment to more than 25,000 patients, including stroke patients. (See Figure 4.) A major telestroke initiative has been taken up by the state of Himachal Pradesh (HP). Telestroke Management Program has been piloted for the first time in HP in collaboration with AIIMS. Under this program, 18 primary stroke centers are being set up in HP state hospitals, which have CT scan facilities. One hundred and twenty state doctors have been trained and six patients already have been successfully treated under this program. Success of this program will pave the path for comprehensive treatment of stroke patients in more parts of the country.

Research in stroke medicine is another area that has seen improvement with increasing national and international collaborative efforts and improved funding opportunities. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Department of Biotechnology (DBT) and Department of Science and Technology (DST) of the Government of India have increased support for basic and clinical stroke research.

The WHO stroke STEPS I version 7 was tested in the Indian Collaborative Acute Stroke Study (ICASS). During 2002-2004, 2,162 acute stroke cases were identified in the study. Analysis of results confirmed that the incidence of stroke was rising with the advance in age. Presently, there are eight stroke registries based in various states of India. Each registry has independently set up a stroke surveillance system based on the WHO STEPS guidelines7.

Figure 4. Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) telemedicine network6.

The National Stroke registry of the ICMR is being run by the National Center for Disease Informatics and Research, Bangalore, where staff members have started the process of collating data on stroke patients from institutions and individual specialists who have registered with the program. The Indian Stroke Prospective Registry (INSPIRE) is a large, multicenteric prospective pilot registry run by the division of clinical trials, St. John’s Research Institute, Bangalore, with the objective of determining etiologies, clinical practice patterns and outcomes of stroke in India.

By April 2012, the study had enrolled 5,301 patients from 49 cities in 19 states. Data from these registries will provide evidence on mortality and morbidity indicators in India, which could help plan an effective stroke management program. In collaboration with Erasmus University Netherlands, AIIMS has jointly launched a large cOHORT study comprising 15,000 people above the age of 50 in rural and urban populations to prospectively examine the causes of stroke and dementia in the Indian population. The Department of Biotechnology has generously funded this endeavor with INR 340 million.

Increasing Stroke Awareness

Education programs are being carried out by hospitals and stroke support groups especially around the World Stroke Day to educate and disseminate information on stroke8. Initiatives include patient awareness programs with lectures and interactions focused on stroke symptoms, the concept of “time is brain,” the need to reach a hospital early and preventive strategies to reduce stroke occurrence; banners, advertisements and write-ups in newspapers along with talk shows on TV and radio channels are also used.

Figure 5. Educational workshop on stroke conducted by Department of Neurology AIIMS.

Studies have shown that lack of physician awareness delayed arrival of stroke patients to a specialized center. CMEs, physician training programs and conferences are regularly held across the country emphasizing the need for recognition and timely therapy and to appraise doctors regarding the newer developments on cerebrovascular disorders. (See Figure 5.) The Indian Stroke Association (ISA) has been organizing a stroke summer school since two years ago to train junior neurologists and physicians.

The annual meetings of ISA are well attended with invited national and international faculty and deliberations on various aspects of stroke. The national guidelines for the management of stroke in India were developed with an aim to close the gap between best and pragmatic practice. A recent study from an academic hospital in North India observed that education to the emergency staff led to an increased rate of thrombolysis and shortened door to needle time. It is encouraging to see that students trained at academic centers are now promoting stroke awareness and timely treatment in smaller cities.

The Future of Stroke Care in India

We will never be able to treat every stroke in the country for a long time to come. So where should our emphasis lie? Preventing as many strokes as possible will probably be the best stroke care that we can provide. At present, many, if not most, strokes are a consequence of modifiable risk factors such as obesity, hypertension and smoking.

Spreading awareness on a war footing and reducing preventable strokes immediately is required. Implementation of mass screening has been recommended to reduce the burden of stroke through identification of people at high risk. Simple, practical and cost-effective measures such as identification and treatment of hypertension in the community will go a long way. Focus also should be on effective implementation, monitoring and evaluation of present stroke programs. A stroke prevented is a much happier situation than a stroke treated.

References:

1. http://www.sancd.org/Updated%20Stroke%20Fact%20sheet%202012.pdf. Stroke in India Factsheet (Updated 2012). Accessed September 6, 2014.

2. Pandian JD, Sudhan P. Stroke epidemiology and stroke care services in India. Journal of Stroke. 2013;15:128-34.

3. Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Islam S, Li W, Liu L, Bo J, Lou Q, Lu F, Liu T, Yu L, Zhang S, Mony P, Swaminathan S, Mohan V, Gupta R, Kumar R, Vijayakumar K, Lear S, Anand S, Wielgosz A, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, Yusoff K, Ismail N, Iqbal R, Rahman O, Rosengren A, Yusufali A, Kelishadi R, Kruger A, Puoane T, Szuba A, Chifamba J, Oguz A, McQueen M, McKee M, Dagenais G; PURE Investigators. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2014;28:818-27.

4. http://health.bih.nic.in/Docs/Guidelines/Guidelines-NPCDCS.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2014.

5. Srivastava PV, Sudhan P, Khurana D, Bhatia R, Kaul S, Sylaja PN, Moonis M, Pandian JD. Telestroke a viable option to improve stroke care in India. Int J Stroke. 2014 Jul 18. [Epub ahead of print].

6. http://www.telemedindia.org/isro.html. Accesssed October 4, 2014.

7. Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Stroke prevention in poor countries. Time for action. Stroke 2007;38:2871-2872.

8. World Stroke Day celebrations: report from India. International Journal of Stroke. 2009;4:231–232.

Additional professor: Pranjal Sisodia, MSc, PhD Scholar, Department of Neurology, Neurosciences Center, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

To correspond with the author, write to him at rohitbhatia71@yahoo.com.