By Axel Karenberg

Axel Karenberg

There are few other neurological disorders with such a constant presence in literary works as apoplexy. As early as 1600, the notions “apoplexy” and “apoplejàa” appear in dramas written by Shakespeare and Lope de Vega. More detailed descriptions of the disease enrich popular novels of the 19th century. Authors such as Balzac, Dumas, Flaubert and Zola must be mentioned here as well as the epical sagas of Dostojewski and Tolstoi 1,2. The American author John Steinbeck used a “stroke” in his work East of Eden as did Philip Roth in his morbid narratives. In the German-speaking world, stroke is dealt with in more than 100 fictional works.

Naturally, literary productions treating this subject resort to contemporary medical knowledge 3. Until the middle of the 20th century, literature focused mainly on two aspects of apoplexy: its typical symptoms and explanations of its origin. The presentation of symptoms abide by a strict code: sudden onset, motor deficiency and unfavorable outcome. The majority of authors was deeply impressed by the loss of the ability to produce speech — above all after Goethe’s early depiction of motor aphasia in Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (VII,6; 1795/96): “Altogether unexpectedly my father had a shock of palsy; it lamed his right side, and deprived him of the proper use of speech. We had to guess at everything that he required; for he never could pronounce the word that he intended … His impatience mounted to the highest pitch: his situation touched me to the inmost heart.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), author of “Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship.”

The diverse causes of the disease taken up in the “belles lettres” reflect its multifactorial origin conceived in premodern medicine. Melancholic “gloominess” or “thick blood” was grounded on the ancient idea of an abnormal blending of the bodily humors. In this perspective, the disease could be provoked by the “cold and moist evening air” or by “taking a bath at 9° C.” (e.g. in E.T.A. Hoffmann, 1825 and in Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest, 1894/95). Only approaching present times, the thematic focus and the narrative perspective shifted slowly but constantly. Along with a more detailed description of the symptoms, the story is now set in hospitals and rehab centers and supplemented by technical diagnosis and therapeutic options. To exemplify this shift, there are George Simenon with his Non-Maigret book The Bells of Bicetre (1962) and Kathrin Schmidt’s novel You Won’t Die (2009).

In literary works, apoplexy serves different goals. The sudden outbreak of the disease can set the plot going, let take it the defining turn or end a story line. Above all, in recent prose texts, the symptoms bring the fictional patients to get to the bottom of their former life. But the illness also can assume a metaphoric function. The recurrent cerebral insults of the protagonist Oblomow in Iwan A. Gontscharows’ homonymous epic (1859) were meant to illustrate the agonizing czaristic feudal system. In a similar way, the American author John Griesemer in his New York novel Heart Attack (2009) fixed the acute symptoms of his protagonist on 9-11 in order to link individual and collective fate, facts and fiction to a meaningful picture.

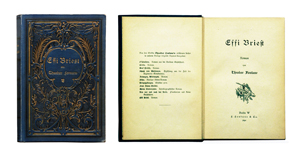

Effi Briest by Theodor Fontane. Original cover of the first edition (1896).

Fictional texts are never bare clinical case histories, they never render exclusively neurological textbook knowledge. It is the components that lie beyond the medical horizon that arouse the interest of physicians and a broader public. The anthropological dimension, the look at human despair and hope can further the understanding of a patient’s fate and help to support present-day stroke medicine.

References

- Perkin JD. The neurology of literature. In: Bogousslavsky J et al. (eds.): Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists, Part 3. Basel: Karger 2010, pp. 227-37.

- van den Doel EM. Balzac’s serous apoplexies. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:1303-5.

- von Engelhardt D. Neurologische Erkrankungen im Medium der Literatur. In: Kömpf D (ed.). 100 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Berlin: DGN 2007, pp. 346-53.

Karenberg is from the Institute for the History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, at the University of Cologne, Germany.