The 32nd ICCN 2022 in Geneva, Switzerland, encompasses 38 education courses and 66 scientific sessions, with 286 speakers. The “Eighth International Conference on Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation” will take place as part of ICCN, consisting of 38 Brain Stim talks (both courses and sessions as a continuous track).

The 32nd ICCN 2022 in Geneva, Switzerland, encompasses 38 education courses and 66 scientific sessions, with 286 speakers. The “Eighth International Conference on Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation” will take place as part of ICCN, consisting of 38 Brain Stim talks (both courses and sessions as a continuous track).

Course and symposium tracks are organized into these topics:

- EEG and MEG

- Brain Stimulation

- Peripheral Neurophysiology

- Brainstem Neurophysiology

- Pediatric Neurophysiology

- Intraoperative Neuromonitoring

- Intensive Care Neurophysiology

Plus, ICCN will host over 300 posters, plus an exhibit hall of related products and services.

Late-breaking poster abstracts can be submitted until June 30.

Here is the link to the preliminary program: https://ifcn.site-ym.com/mpage/ProgrammeOverview.

For more information, visit: http://www.iccn-congress.org. See you in Geneva! •

In this month’s neurology and

In this month’s neurology and  The Indian Academy of Neurology is highly committed to public education and awareness activities regarding neurological disorders. It carries these events throughout the year. The idea is to educate general public about the disorders in order to help them for early diagnosis and better patient care. In view of the COVID pandemic, these activities were organized as virtual meetings and were well attended. The audience also got the opportunity to interact with the experts.

The Indian Academy of Neurology is highly committed to public education and awareness activities regarding neurological disorders. It carries these events throughout the year. The idea is to educate general public about the disorders in order to help them for early diagnosis and better patient care. In view of the COVID pandemic, these activities were organized as virtual meetings and were well attended. The audience also got the opportunity to interact with the experts.

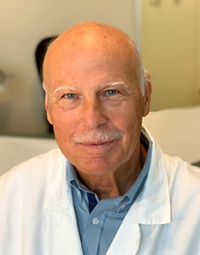

Dr. Jun Kimura was born on Feb. 25, 1935, in Kyoto, Japan, and was brought up in Takayama, a scenic rural place near Kyoto. He once graduated from School of Technology in 1957, but re-entered Medical School of Kyoto University, and obtained MD (1961). He was granted a Fulbright Scholarship (1962-1967), and began his career at the University of Iowa School of Medicine as a medical resident and fellow (1962-1968), associate professor (1972-1977), and professor (1977-1988).

Dr. Jun Kimura was born on Feb. 25, 1935, in Kyoto, Japan, and was brought up in Takayama, a scenic rural place near Kyoto. He once graduated from School of Technology in 1957, but re-entered Medical School of Kyoto University, and obtained MD (1961). He was granted a Fulbright Scholarship (1962-1967), and began his career at the University of Iowa School of Medicine as a medical resident and fellow (1962-1968), associate professor (1972-1977), and professor (1977-1988).

World Brain Day (WBD) 2022 is dedicated to the theme “Brain Health for All” as our brains continue to be challenged by pandemics, wars, climate change, massive disparities in health equity and myriad preventable diseases.

World Brain Day (WBD) 2022 is dedicated to the theme “Brain Health for All” as our brains continue to be challenged by pandemics, wars, climate change, massive disparities in health equity and myriad preventable diseases.