A forgotten paradigm involving the pineal gland.

By Peter J. Koehler

Figure 1. Drawing of René Descartes by Jan Lievens, 1644-1649. Collection Groninger Museum, on loan from Municipality of Groningen, donated by Hofstede de Groot, Photo © Marten de Leeuw.

Some time ago, I wrote about brain stones, intracranial calcifications that have been found at autopsies for many centuries. (See World Neurology, January 2017) In this context, the pineal gland was in the spotlight after the French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650, see Figure 1) wrote down his ideas about the physical part of the soul supposedly localized in this structure.1

In the subsequent 150 years, there were lively discussions between physicians, who were proponents and opponents of this idea. The finding of stones in this organ played an important role. It was only around 1800 — when critical observers began to apply the numerical method, as Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis (1787-1872) did for bleeding2— that physicians began to realize that discovering a stone in the pineal gland was a normal finding above a certain age. More than 100 years later, there was renewed interest in the pineal gland at a time when extracts from all kinds of organs were used to treat diseases, in particular mental deficiency. The term organotherapy was introduced for this purpose.

Figure 2. Portrait of Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard (© Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire Santé).

Organotherapy

French physician and physiologist Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard (1817-1894; see Figure 2) came up with the idea of extracting therapeutic fluid from glands.

He and his predecessor at the Collège de France in Paris, physiologist Claude Bernard (1813-1878), who described glucose as an internal secretion of the liver, are considered founders of endocrinology. Brown-Séquard formulated early ideas of glands with internal secretion and experimented with extracts of all kinds of organs.3,4 He had first suggested administering seminal fluid intravenously to old men in order to rejuvenate them in 1869.5 Following years of experimentation with gland extracts, including the application of testicular gland extracts on himself — claiming that it had led to improvements in his bodily functions and intellectual faculties — he published a kind of review paper in the British Medical Journal (1893). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. Brown-Séquard’s publication in the British Medical Journal of 1893

Brain Extracts

Brown-Séquard provided the methods to produce the extracts and presented the work that he had conducted on several organ extracts, including the pancreas, liver, thyroid, and sexual organs. Interestingly, he also wrote that “the cerebral or medullary liquid, extracted either from the grey or white matter of the cerebrospinal centers, has been most extensively used.” It had been used for the treatment of neurasthenia, locomotor ataxia [tabes dorsalis], and epilepsy.6 The treatment of neurasthenia — a popular diagnosis at the end of the 19th century7— was reported successful in 50% to 60% of patients. Brown-Séquard attributed this effect to the invigoration of the nervous system and the enhancement of cell regeneration.

In the same year, the New York Therapeutic Review published “Injections of Organic Fluids According to Professor Brown-Séquard’s Method.” It praised the use of organ extracts for the treatment of a range of illnesses — in particular of the nervous system — including chorea, epilepsy, locomotor ataxia, and neurasthenia. It claimed that extract of pancreas could be used to treat diabetes, extract of grey matter could treat neurasthenia, and testicular extracts could be used to treat a range of diseases.4 However, as definitions of diseases were not always clear, scientific criticism was not long in coming. Solomon Solis-Cohen (1857-1948), professor of clinical medicine and applied therapeutics at the Philadelphia Polyclinic, criticized the use of brain extracts. Unlike the thyroid gland, he wrote that “the brain, so far as we know, secretes nothing physical. So far as we know, there is no symptom or symptom-complexus which can be attributed to defect in any supposed secretory function of the brain.”8

Chastity Gland

In his informative article on the history of ideas on the pineal gland, neurologist and medical historian Francis Schiller (1909-2003) pointed to another connection with endocrinology.9 In 1898, Otto Heubner (1843-1926, eponymist of Heubner’s recurrent artery) described a 4-year-old child suffering from pubertas praecox — the premature development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics — caused by a pineal gland tumor. Ideas arose as to whether the pineal gland might have an inhibiting effect on sexual development.

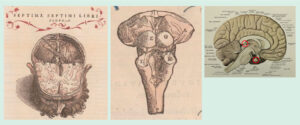

In the early 20th century, the Viennese neurologist Otto Marburg (1874-1948) suggested the pineal gland functions in normal conditions as a Keuschheitsdrüse [chastity gland], suppressing the premature development of sexual characteristics.8 The American neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing (1869-1939) pointed out an antagonism with respect to human sexual development between the pineal gland (epiphysis) and the pituitary gland (hypophysis), not only with respect to their position above and below the brain, but also in function when it comes to tumors. (See Figure 4.)

Tumors of the pineal gland would cause premature development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics, whereas those in the pituitary gland would destroy hormonal regulation and lead to the contrary. In 1912, Cushing wrote: “[The pineal gland] is undoubtedly of physiological importance … it would appear that there is a measure of antagonism, insofar as sexual development is concerned, between hypophysis and epiphysis. However, it must be confessed that the syndrome of supposed pinealism has been observed only in connection with tumors of the gland which have led to an obstructive hydrocephalus and thus of necessity to secondary hypophysial disturbances.”8

Figure 4. Pineal gland (at L on the left and at D on the middle figure) from Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica of 1543.10 The figure on the right is a modified sagittal view from the early 20th century, showing both glands.11

Pineal Gland Extract for Mental Disability

In his book The Origins of Organ Transplantation, medical historian Thomas Schlich wrote that “organotherapy was generally rejected around 1900, since neither the clinical data nor the experimental results were considered adequate evidence for its effectiveness.”5 However, in neurology as well as psychiatry, organ extracts continued to be applied. The term endocrine psychiatry has been applied to the latter.

In the 1910s, researchers H.H. Goddard and Walter S. Cornell in Vineland, New Jersey, working under Charles Loomis Dana (1852-1935), professor of nervous diseases at Cornell Medical College, New York, and physician William Nathaniel Berkeley (1868-1928), author of The Principles and Practice of Endocrine Medicine (1926), studied the function of the pineal gland. They were interested in feeding experiments.12 Pineal gland abstract was given orally to 25 children. Each child was paired with a control who was not given treatment. After two months, the effect was not clear, and the experiment was extended for another two months. They concluded that “one cannot but feel that there is a distinct influence in the extract toward mental power.” They compared it with the influence of thyroid extracts on children suffering from congenital iodine deficiency syndrome.13

Meanwhile, Berkeley published on improvements he had achieved with “the use of pineal gland in the treatment of certain classes of defective children” and in 12 patients with pre-senile dementia.14,15 The Austrian philosopher and esotericist, founder of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) prescribed pineal gland extracts for children with mental disabilities.9

Pineal Gland Extract for Psychosis

It was also administered to psychotic patients as was recently reviewed in “Organ Extracts and the Development of Psychiatry: Hormonal Treatments at the Maudsley Hospital 1923-1938.”16 No less than 17 studies on pineal gland extracts for schizophrenia were found before 1950.8

In 1921, the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde reviewed a study on the pineal gland, reporting its influence on psychic functions. In some types of insanity — in particular schizophrenia — extracts of the gland were believed to inhibit signs of sexual overstimulation. Apparently, the drug was available under the name Epiglandol.17 The interest in a possible relationship between schizophrenia and the pineal gland did not terminate after the discovery of the secretion of melatonin in 1958.18,19 •

References

1. Descartes R. (1649) Passions de l’âme. Le Gras, Paris.

2. Morabia A. Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis and the evaluation of bloodletting. J R Soc Med. 2006 Mar;99(3):158-60.

3. Aminoff MJ (2011). Brown-Séquard: An Improbable Genius Who Transformed Medicine. Oxford, University Press: 235-260.

4. Borell, M. (1976) Brown-Séquard’s organotherapy and its appearance in America at the end of the nineteenth century. Bull Hist Med 50: 309–320.

5. Schlich, T. (2010). The Origins of Organ Transplantation. Rochester: University of Rochester.

6. Brown-Séquard CE (1893) New therapeutic method consisting in the use of organic liquids extracted from glands and other organs. Brit Med J 1:1145-1147;1212-1214.

7. Gijswijt-Hofstra M. Introduction: Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War. Clio Med. 2001; 63:1-30.

8. Solis-Cohen S (1893). The therapeutic properties of animal extracts. Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine, vol. II, no. 11, pp.309-18. Available via The therapeutic properties of animal extracts – Digital Collections – National Library of Medicine (nih.gov) ; accessed August 11th, 2024.

9. Schiller F (1995) Pineal gland, perennial puzzle. J Hist Neurosci 4:155-165.

10. Vesalius (1543). De humani corporis fabrica, Libri septem, Basel, Ioannis Oporini, pp. 611 and 615. Available via https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/content/titleinfo/6299027 ; accessed August 11th, 2024.

11. Sobotta J (1920) Atlas der deskriptiven Anatomie des Menschen. 3rd part. Lehmanns, München, p. 606.

12. Dana CL, Berkeley WN. The functions of the pineal gland. With report of feeding experiments by Goddard, H.H., Walter S Cornell. Medical Record 1913; 83:835.

13. Goddard HH. The Vineland experience with pineal gland extract. JAMA 1917; 18:1340-1.

14. Berkeley W (1914) The use of pineal gland in the treatment of certain classes of defective children. Medical Record 85:513–515.

15. López-Muñoz F, Molina JD, Rubio G et al (2011) An historical view of the pineal gland and mental disorders. J Clin Neurosci 18:1028-1037.

16. Evans B, Jones E (2012) Organ extracts and the development of psychiatry: hormonal treatments at the Maudsley Hospital 1923-1938. J Hist Behav Sci 48:251-276.

17. Koopman. Nieuwe onderzoekingen over de pijnappelklier. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1921; 65:1449-50.

18. Kappers JA. The mammalian pineal gland, a survey. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1976;34

(1-4):109-49.

19. Wurtman RJ. Melatonin as a hormone in humans: a history. Yale J Biol Med. 1985 Nov-Dec;58(6):547-52.