By Peter Koehler

“Cutting the stone” is the title of a well known painting (1494) by Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450-1516), who died 400 years ago. The painting is displayed at the Prado Museum in Madrid. Another name by which the painting is known reads, “The extraction of the stone of madness or the cure of folly.” An inscription on the painting says (in old-Dutch), “Meester snijt die keie ras, Mijne name is Lubbert Das,” which in English would read, “Master, cut away the stone soon, my name is Lubbert Das.” In Dutch literature of the day, the name was given to a comical character. The theme was well known at the time, and the scene depicted by several other painters, including Pieter Brueghel (senior), Peter Huys, and Jan Steen. The idea of a stone in the brain made me think of a discussion taking place in medical literature over a century later.

The Seat of the Soul and the Pineal Gland

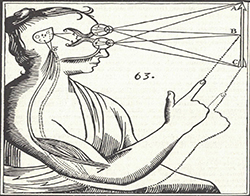

Figure 1. From Gregor Reisch (Margarita Philosophica cum Additionibus Novis, 1517) depicting the localization of the functions of the soul: sensorium commune and imaginatio in the first cell (lateral ventricles), cogitatio (reasoning) in the middle, and memory in the posterior cell (our fourth ventricle).

Looking at medical literature of the 17th century (and at CT scans nowadays), we know that calcifications within the skull really exist. An issue from this period that is of particular interest with this respect deals with the seat of the soul. Through the ages, the seat of the soul has been localized in various structures. In the ancient Greek period, mental functions, including memory, imagination, and thinking, were discerned. The concept of sensorium commune referred to the part of the mind that brings together the impressions from all five senses. It goes back to Aristotle, who localized the sensorium commune (the seat of the soul) in the heart, whereas Hippocrates and Galen localized it in the brain. For many ages, the soul, the immaterial part of human being, was localized in the cerebral ventricles or cells (Figure 1), in which model the lateral ventricles were considered one cell. In the first cell, imagination was localized; in the second, thinking or reasoning was localized; and in the third cell (our fourth ventricle), memory was localized.

The localization of the soul changed in the 17th century, among others by René Descartes (1596-1650), who, as is well known, made a clear distinction between body and mind, and localized the soul in the pineal gland. In a rational way, he became convinced that sensory information from the body should convene in one place, an unpaired organ that he usually called “la petite glande,” the small gland. This is the place where he localized the sensorium commune, imagination, as well as thinking. It was the seat of the soul, he believed, situated between the beginning of the aquaduct of Sylvius that connects the (present) third and fourth ventricles. An important argument for Descartes, who stayed in the Netherlands for a large part of his life (1628-1649), was that this would be the place where the two images from each eye come together and form one image. The pineal gland is the only unpaired organ where this could take place and, moreover, it lies in the extension of the optic tracts. (Figure 2.)

A Stone in the Pineal Gland

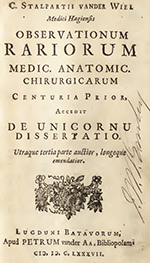

Not everyone was convinced of this localization. One of the physicians, who opined differently, was the Dutch Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel (1620-1702). He had studied at the University of Franeker (no longer existent), where he also wrote his thesis and practiced in the city of The Hague, where his father had been mayor. In 1682, he published his experiences of 40 years of medical practice in the book Hondert seldzame aanmerkingen, so in de Genees- als Heel- en Snijkonst [Hundred rare comments, in medicine as well as surgery and dissection; also published in Latin, Figure 3, and French]. He wished to pass on his experiences to his son Pieter, who would succeed him six years later. The 12th chapter is titled “Steen in de Pijn-appel-klier en Saadtvaten gevonden” [Stone found in the pineapple gland and seed vessels]. The text reads “When the body of a certain woman was opened by my brother the physician Johan Stalpart van der Wiel, here at the dissecting room some years ago, I have seen that a small stone, the size of a hempseed, was found in the pineapple gland…” Being aware of Descartes’ opinion, he concluded “that aforementioned gland cannot be the seat of the soul, nor that the most important faculties or acting powers (as has been made up by some) have their origin here.” Moreover, Stalpart van der Wiel argued that the gland “in animals, who seem to have no imagination, no memory, nor any remarkable powers of the soul” was found to be fairly large.

Indeed, it had been a well-known fact that the pineal gland could easily be missed at autopsies of human beings. Galen was aware of the gland, but most probably did his research in cattle. At a public anatomy lesson in Leiden (1637), Professor Adriaen van Valkenburg (Falcoburgius, 1581-1650) admitted, if requested, to René Descartes, who attended the lesson, that he had never found the gland in human beings.

Brain Stones

Stalpart van der Wiel’s case description is followed by an extensive discussion of contemporary literature, referring to his Dutch compatriots Reinier de Graaf, Job van Meekeren, Justus Schraderus, and the Danish Thomas Bartholinus. Stones had been found in several body parts as had been noted by many physicians. Several of them had written that these could be found in various places within the head. Stalpart referred, for example, to the German physician Johannes Schenckius (in Lithogenesia) and the French Isaac Cattierius (Cattier, physician to the king), who, in his Observationes medicinalis (1653), published a case of a stone growing attached to and under the dura mater. The list of references provided by Stalpart van der Wiel is quite large. A certain Kentmannus (lib. de Lapid in corpori inventis or book on stones found in the body) relates of a stone found in the brain with the form and size of a mulberry. Furthermore, the Dutch Theodor Kerckring (observ. 35) is referred to, who had found a stone the size of a hazelnut in the right ventricle.

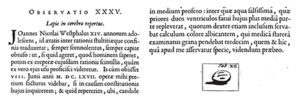

Although I was unable to check all references by Stalpart van der Wiel, the latter book by Kerckring could easily be found. Theodor Kerckring (1638-1693; Figure 5), often working with a microscope made by his former schoolmate (at Van den Enden’s Amsterdam Latin school) Baruch Spinoza, became well known because of his description of the circular folds of the intestine. In his Spicilegium Anatomicum (Figure 6) of 1670 there is indeed a chapter named “Lapis in cerebro repertus” [Stone found in the brain]. It is about the 14-year old boy Johannes Nicolai Westphalus, who died June 8, 1667. At autopsy, hydrocephalus was found, probably caused by a white calcification of the right ventricle (Figure 7a and 7b).

Another interesting case referred to by Stalpart van der Wiel is that of a stone the size of a Turkish bean, which was found at the origin of the optic nerves and that had caused headache and blindness (referring to Zodiaco Med. Gall. anni 1, fol. 81).

Concluding Remarks

Although the scene on Bosch’s painting — in fact, not a stone but a flower appears from the skull — obviously is a critical depiction of credulity of common people on one side and quackery on the other. Several other interpretations have been given, but brain stones, as we know today, are not only a fantasy, and a touch of truth is present. In a recent paper, Celzo et al. (Insights Imaging 2013;4: 625–635) provide a pictorial review of brain stones with modern illustrations. They distinguish intra- and extra-axial stones. The first comprise stones of various origin, including neoplastic (oligodendroglioma), vascular (arteriovenous malformations), infectious (toxoplasmosis, rubella, etc.), congenital (Sturge-Weber syndrome) and endocrine/metabolic (Fahr’s syndrome) origin. The extra-axial stones find their origin in tumors (meningiomas) and exaggerated physiological calcifications. The authors conclude that “brain stones are more common than previously thought.” Although Stalpart van der Wiel was already aware of this, he would have been interested to read this paper and to realize that it is even more frequent than he thought.