By Girish Modi

Girish Modi

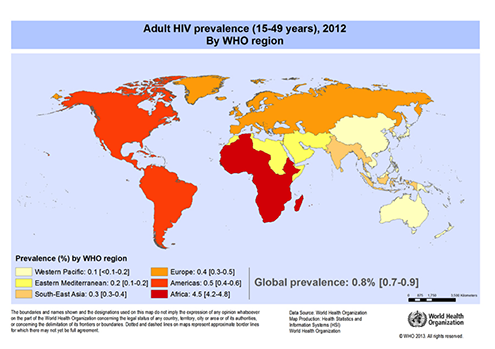

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 75 million people worldwide have been infected by the HIV virus. About 36 million people are estimated to have died as a result of being infected. At the end of 2012, globally 35.3 million [32.2–38.8 million] people were living with HIV. In the young, economically active adult population (15 – 49 years) 0.8 percent are living with HIV.

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the brunt of this burden and remains the most severely affected. In Sub-Saharan Africa, one in every 20 adults are HIV infected accounting for 71 percent of the people living with HIV worldwide.

In South Africa, the total number of persons living with HIV increased from an estimated 4 million in 2002 to 5.26 million by 2013. For 2013, an estimated 10 percent of the total population is HIV positive. Also, 17 percent of South African women in their reproductive ages are HIV positive.

These statistics are important to help understand the impact they have had on the practice of clinical medicine in Sub-Saharan Africa and for us here in South Africa. In the teaching public hospitals in South Africa, 40-60 percent of medical admissions are in some way linked to HIV infection. In the non-teaching rural hospitals, these figures are much higher.

Naturally, neurology has been affected and to a large extent has borne the brunt of this epidemic. Neurological involvement in HIV is described to affect 40-75 percent of HIV infected patients admitted to the medical wards in a tertiary care setting1. In a prospective study of 506 in-patients at the Helen Joseph Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, 75 percent of patients had some clinical neurological involvement, and in 11 percent neurological disease was the sole presenting feature. The neurological presentation of the patient is dependent and to an extent determined by the immunological state of the patient.

Seizures and Epilepsy in HIV

Seizures in HIV can occur at any stage of the infection and have been described in patients with presumed acute HIV induced seroconversion illnesses through to advanced disease or AIDS.

Incidence data on seizures in HIV infection has mostly been focused on new onset seizures (NOS). All the studies have been hospital-based and most are retrospective. The incidence ranges from 2-20 percent. The differences in incidence can be explained by the different inclusion and exclusion criteria in the studies and the specific groups surveyed. The relatively low incidence of two percent was from a study in New York where patients with provoked seizures were excluded. The high incidence of 20 percent came from Bangalore in India where the study population group was pre-selected in that all their patients had a pre-existing neurological disorder.

Incidence data on seizures in HIV infection has mostly been focused on new onset seizures (NOS). All the studies have been hospital-based and most are retrospective. The incidence ranges from 2-20 percent. The differences in incidence can be explained by the different inclusion and exclusion criteria in the studies and the specific groups surveyed. The relatively low incidence of two percent was from a study in New York where patients with provoked seizures were excluded. The high incidence of 20 percent came from Bangalore in India where the study population group was pre-selected in that all their patients had a pre-existing neurological disorder.

In terms of seizure types, in these study populations, generalized seizures were by far the commonest occurring in 58-100 percent of patients. This high proportion may be due to the under-reporting of focal origin seizures that cause immediate secondary generalization or inaccurate details from eyewitnesses. Focal seizures may in some patients indicate the presence of an underlying focal brain lesion but they have also been described in patients with diffuse disease. Status epilepticus also occurs in this population group and has been described in 8-18 percent of patients.

In terms of causes, NOS in HIV positive persons can be categorized or grouped into:

- Focal brain lesions (FBL)

- Meningitis

- Metabolic causes

- No identifiable cause (NIC)

The majority of patients with NOS have a specific underlying cause for their seizure.

The most commonly identified causes are focal brain lesions (FBLs) and meningitis. FBLs occur in 30-50 percent of patients. FBLs can be infectious; neoplastic; demyelinating or due to cerebrovascular disease. Toxoplasmosis has been identified as the commonest infectious cause of FBLs in patients with HIV and occurs in up to 88 percent of patients presenting with NOS in most of the studies that have been published. However, in populations where tuberculosis is endemic, this has been found to be the commonest cause of FBL in HIV patients with NOS. CNS lymphoma is recognized as the second most common cause of FBL and has been reported in up to 11 percent of patients. Other reported causes of FBL include Progressive Multi-focal Leukoencephalopathy (PML); neurocysticercosis and strokes.

Meningitis has been described in 10-22 percent of patients presenting with NOS. Cryptococcal meningitis is the most frequent cause of meningitis except again in regions where tuberculosis is endemic.

The other aetiologies that need to be considered include metabolic abnormalities; medication side-effects and HIV-Associated Dementia (HAD).

In 6-46 percent of patients, NIC can be found for the seizure presentation and it is presumed that primary cerebral HIV infection is responsible. In keeping with this, SPECT scan studies have shown focal temporal lobe abnormalities.

Numerous abnormal electroencephalographic (EEG) findings have been reported in HIV-infected individuals presenting with seizures. The abnormalities have been both focal and generalized and are most commonly non-specific e.g. generalized slowing. Non-specific abnormalities have been well described in asymptomatic HIV-positive individuals and their significance in this setting is uncertain. Focal abnormalities on EEG do not necessarily signify an underlying focal lesion.

Seizures recurrence risk as expected from the potential causes listed above is high and therefore treatment even with a new onset first seizure requires medical intervention. Valproate has been described to increase viral replication but it has also been shown to be beneficial in HIV infected seizure patients and is therefore widely used. Phenytoin and carbamazepine induce the hepatic p450 system and interact with anti-retrovirals adversely and are therefore not recommended. Gabapentin, Levetiracetam and Lamotrigine do not have such interactions are preferred in the setting of HIV and seizures. Availability in resource limited regions is an issue with these anti-epileptics.

In an acute setting, standard epilepsy protocols should be adhered to. Long-term anti-epileptic therapy needs to be initiated in the majority of patients but this can be a difficult decision. Evidence-based guidelines (American Academy of Neurology) have been formulated for patients that require both HAART and anti-epileptics. The guidelines do not however specify when anti-epileptics should be initiated or how long they should be continued for.

Epilepsy and HIV remains a daunting neurological challenge.