National drug regulatory authorities should prioritize essential medicines to ensure availability.

By Brhlikova, P., Walker, R., Fothergill–Misbah, N., Pollock, AM.

The Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and other Neurological Disorders (IGAP) 2022-2031 recognizes the gap in availability of essential medicines to treat neurological disorders1 and the need for health system strengthening to ensure access to them. Access to essential medicines is fundamental to the human right to health and is enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

On July 26, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the 23rd edition of its Model List of essential medicines. This important concept deserves wider attention from policymakers and physicians worldwide. First launched by WHO in 1977 in response to concerns raised by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) about the need to prioritize medicines for use in their underresourced health systems in the face of an avalanche of new drugs being brought to market, it is now used to guide the development of national Essential Medicine Lists (EMLs) in 137 countries to promote access to appropriate medicines. It is also used as the basis for government procurement, pricing, and underpins standard treatment guidelines and rational prescribing.

Although essential medicines are intended to address the priority health care needs of populations and should be available at all times, many LMICs struggle to make them available, and affordable, and many millions of people must go without the medicines they need. Some therapeutic classes are affected more than others. The main reasons for this are perceived demand, restricted budgets for government procurement, lack of health professionals, and/or because the medicine is not licensed for use in the country.

Table 1. Number and proportion of all, anti-epileptics and antiparkinsonism essential medicines without a registered product based on National Drug Registers (February 2018) and Essential Medicines List (EML) 2016 for Kenya, 2017 for Tanzania, and 2016 for Uganda.

(Source: Green et al. 2023)

Even when medicines are listed on national EMLs, a fundamental problem is the disconnect between EMLs and drug registers. National drug registers (NDRs), or national registers of authorised medicines, are government lists containing information on medicinal products authorised for use in the relevant country. A medicine cannot be marketed and made generally available in a country unless it is authorised for use in the country by the national medicines regulatory authority. However, the registration process does not prioritize registration of essential medicines for public health need. Rather, the applications for marketing authorizations are made by the manufacturers on the basis of market potential and profit. As essential medicines are usually generic, low-cost medicines, they may not be available because the manufacturers have not applied for a licence.

Curiously, there has been little research to date on how registration in relation to the availability of essential medicines contributes to the treatment gap: most work has focused downstream on availability of medicines in pharmacies, hospitals, and health centers.

In a recent study linking data from drug registers to national EMLs in three countries in East Africa, between over a quarter to a half of essential medicines were not registered: Kenya 28% (175/632), Tanzania 50% (400/797) and Uganda 40% (266/663) 2.

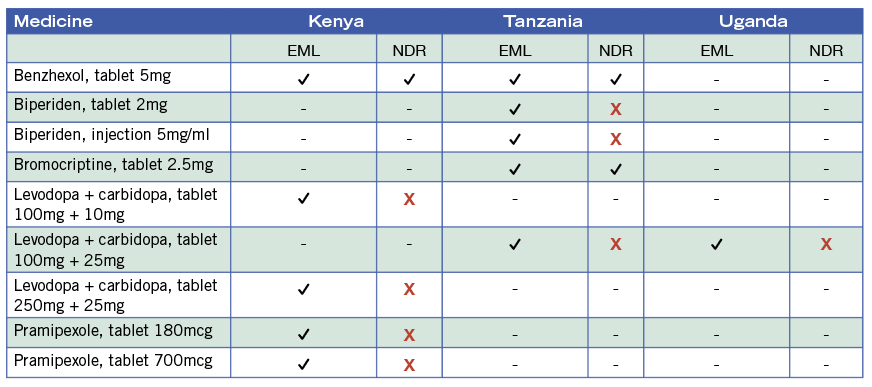

In the anti-epileptics/anticonvulsants class, Kenya lists 18 essential medicines, Tanzania lists 17, and Uganda has 15. However, only up to two-fifths of these were registered at country level (5 in Kenya, 7 in Tanzania, 5 in Uganda). Levodopa/carbidopa remains the gold-standard treatment for Parkinson’s and is on the national EMLs of all three countries: Tanzania’s also includes biperiden as an alternative and Kenya’s includes pramipexole. However, at the time of the study, no EM products were registered in any of the three countries.

In contrast, over-registration of non-essential medicines was found. Of the thousands of registered products on the NDRs, more than half are not essential; in Kenya 71% (4350/6151), Tanzania 64% (2278/3590) and Uganda 58% (2268/3896). High numbers of registered products for specific medicines suggests high market potential and sales for these medicines. This is of concern for several reasons. First, over-registration of non-essential medicines diverts regulatory resources away from public health need toward registering non-priority and, often clinically sub-optimal medicines. Second, the risk of mis-prescribing and inappropriate use and harms is also greatly increased as these medicines will not have standard treatment guidelines (STGs). Third, most medicines are paid for out-of-pocket in these countries and costs of non-priority and sub-optimal medicines overburdens households.

Table 2. Antiparkinsonism medicines listed as essential Kenya (2016), Tanzania (2017), and Uganda (2016) and their registration status (NDR, 2018).

For instance, diclofenac is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used as an analgesic. It has been removed from the WHO Model List due to significant cardiovascular risks and because safer alternatives are available. Despite this, diclofenac remains on the national EML of almost 90% of countries globally and forms one-third of the market for NSAID use in low-, middle- and high-income countries. Of the 219 diclofenac products registered for use across Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda 127 (58%) do not meet strength and dosage form specified in the national EMLs. Pregabalin, an analgesic, is on none of the national EMLs but has 77 registered products across the region.

The essential medicines concept, predominantly used in LMICs, is increasingly being considered by high income countries including Canada. It is crucial to note that the United States, once a consistent opponent of the essential medicines concept, has recently acknowledged its importance3,4.

LMICs could once again lead the way in bridging the treatment gap with essential medicines if they were to prioritize their registration, restrict registration of non-essential medicines and review the registration of the top selling non-essential medicines to ensure rational and appropriate use. •

The authors are from the Population Health Sciences Institute at Newcastle University, United Kingdom.

References

1. World Health Organization. Intersectoral global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022-2031. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076624, accessed 02/10/2023).

2. Green A, Lyus R, Ocan M, Pollock A, Brhlikova P. Registration of essential medicines in kenya, tanzania and uganda: A retrospective analysis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2023:01410768231181263. doi: 10.1177/01410768231181263.

3. Taglione MS, Persaud N. Assessing variation among the national essential medicines lists of 21 high-income countries: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045262. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045262.

4. Brhlikova P, Persaud N, Osorio-de-Castro CGS, Pollock AM. Essential medicines lists are for high income countries too. BMJ. 2023;382:e076783. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076783.