By Anne Hege Aamodt, Espen Dietrichs and Hanne Flinstad Harbo

Anne Hege Aamodt (left) and Hanne F. Harbo introducing the program at the closing ceremony for the Norwegian YotB2015

After an invitation from the European Brain Council, we arranged the Norwegian Year of the Brain in 2015 (YotB2015) – 20 years after the first Year of the Brain in Norway. The Norwegian Neurological Association, the Norwegian Brain Council and Nansen Neuroscience Network coordinated YotB2015 and took the initiative to organize different events and activities. The main goals of YotB2015 were to increase the focus on knowledge and research on brain diseases that would lead to improved prevention, treatment and patient care.

Professor Espen Dietrichs, Norwegian delegate to the WFN presenting one of many lectures during the Norwegian YotB2015.

Upon establishing a national committee in 2014, we exchanged ideas and distributed tasks to stimulate the arrangement of events, media reach and interest-based political work. Many neurological departments, patient organizations, professional organizations and research networks announced the Norwegian Year of the Brain, scheduling activities and events around the country.

The formal opening ceremony was held in February 2015 in the Assembly Hall at the University of Oslo. State Secretary Anne Grethe Erlandsen from the Ministry of Health and Care Service opened the meeting before President Raad Shakir of the WFN, Mary Baker, past president of the European Brain Council, and several Norwegian health leaders, neuroscientists and patients held their lectures and talks.

YotB2015 meeting about treatment of neurological disorders, Oslo University Hospital.

Through the year, more than 60 meetings open to the public were held around the country, including lectures and discussions on different perspectives on neuroscience at hospitals, cultural centres and libraries. In Molde, Norway, YotB2015 meetings were part of an international literature festival. And in Oslo, several large meetings on various neuro-related topics were held, including “Literature and the Brain,” “Music and the Brain” and “Food and the Brain.” In addition, there were multiple professional meetings to market the YotB2015 logo, including the 27th National Neurological Congress, the Spring Meeting in the Norwegian Neurological Association, meetings within the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters and the 1st National Meeting on Endovascular Intervention in Acute Stroke. YotB2015 was also marketed in a stroke campaign. A popular science book about the brain was published by the Norwegian delegate to the WFN, Espen Dietrichs, one of the initiators of both YotB1995 and YotB2015.

From left to right: Brain musicians Kristoffer Lo, John Pà¥l Inderberg and Henning Sommerro; Director of the National Health Directorate Bjørn Guldvog; State Secretary Anne Grethe Erlandsen from the Ministry of Health and Care Service and the Nobel Laureate Edvard Moser together with Hanne Harbo from the Norwegian Brain Council. (Photo courtesy: Norwegian Brain Council.)

During the YotB2015, many neurological topics and challenges were presented in mass media with numerous interviews on TV, radio and newspapers. Information on coming events was continuously updated on the website of the Norwegian Neurological Association and the Norwegian Brain Council. Information was also conveyed through social media platforms, Twitter and Facebook. During the fall, the Norwegian Brain Council also arranged a Facebook campaign called “With a Heart for the Brain,” which generated more than 1 million likes.

Ragnar Stien, one of the initiators of the Norwegian YotB in both 1995 and 2015, and the audience in Domus Academica at the University of Oslo at the meeting “The Literature and the Brain.”

Erlandsen led December’s closing ceremony. The Director of the National Health Directorate and Nobel laureate Edvard Moser held inspiring lectures on the impact of neuroscience and brain disorders. In addition, so-called “brain music” that was specially composed for the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in 2014 by two music professors at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, was presented live for the first time during the closing ceremony.

From left to right: Anne Hege Aamodt, president of Norwegian Neurological Association; Olga Bobrovnikova, renowned pianist battling MS and European Brain Council ambassador; Raad Shakir, WFN president; and Hanne F. Harbo, head of the Norwegian Brain Council. (Photo courtesy: Lise Johannessen Norwegian Medical Society.)

We have been working continuously to strengthen the priority area of brain diseases and neuroscience. The Year of the Brain and the neuro field were discussed in the Norwegian Parliament during 2015. We have also had an audience at the health minister and discussed the focus on brain disorders. The Norwegian Brain Council also received a separate post in the fiscal budget for 2016. During the closing ceremony, the state secretary declared that the Ministry of Health and Care Service will make a status report for brain disorders. A few days later, the Health Committee in the Norwegian Parliament underscored the need for a national plan on brain health in Norway.

The Norwegian YotB2015 has resulted in increased interest and knowledge on neurological disorders. Our message that one in three will experience brain disorders and that the neuro field needs to be prioritized stronger has sparked interest. We have achieved political understanding for brain disorders as a focus area and will work further with this issue. We will follow up the announced status report, which should result in a National Brain Plan.

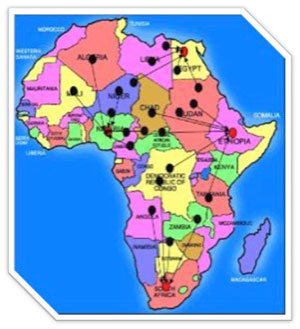

Although ancient Egyptians were the first to describe the brain, the services that are provided to patients with disorders of the brain and the number of trained neurologists in Arab and African countries is at best centralized in large cities and at worst nonexistent.

Although ancient Egyptians were the first to describe the brain, the services that are provided to patients with disorders of the brain and the number of trained neurologists in Arab and African countries is at best centralized in large cities and at worst nonexistent.

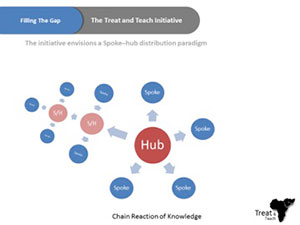

For the aforementioned reasons, Ain Shams University has been endorsing an initiative called Treat and Teach, which is designed to develop short- and intermediate-term strategies to reduce the gap in the number of trained neurologists and the deficiency of neurology education programs in Africa. We are trying to complement the current efforts to improve neurology education in Africa with an initiative that has a mix of online education and on-site clinical training, while working on establishing medical services that may include a stroke unit, memory clinic, neurorehabilitation units, or a neurology department. Master degrees will be given from Ain Shams University, Cairo, and work will be done to establish local master degrees in rural centers. This could lead to national neuroscience services run by local providers.

For the aforementioned reasons, Ain Shams University has been endorsing an initiative called Treat and Teach, which is designed to develop short- and intermediate-term strategies to reduce the gap in the number of trained neurologists and the deficiency of neurology education programs in Africa. We are trying to complement the current efforts to improve neurology education in Africa with an initiative that has a mix of online education and on-site clinical training, while working on establishing medical services that may include a stroke unit, memory clinic, neurorehabilitation units, or a neurology department. Master degrees will be given from Ain Shams University, Cairo, and work will be done to establish local master degrees in rural centers. This could lead to national neuroscience services run by local providers.