Philippe Fermin’s Observations in 18th-Century Surinam

BY Peter J. Koehler, MD, PhD

Fig. 1. Title page of Fermin’s Traité des Maladies (1764)

The stay of Europeans in tropical countries offered opportunities for the observation not only of unknown (manifestations of) diseases, but also of the flora and fauna of these areas. Extensive descriptions were published in books, and specimens were brought to Europe, where cabinets of curiosities were filled with objects from natural history, archeology, geology, and ethnology.

Fermin

One of the adventurers who visited a Dutch colony was Philippe Fermin (1729-1813). The son of French Huguenots was born in Berlin and went to the local French gymnasium. Then he moved to London, where he apprenticed with an elderly physician. Not wishing to have to train for several years, he obtained a certificate for the practice of surgery in Rotterdam and, at the age of 25, he moved to Surinam (a former Dutch colony, now the Republic of Suriname) in 1754 to serve for the government. He was offered 20 florins a month for providing medication. Although he realized that his training had been insufficient, he started to practice. Much of the information that is known about him was provided by his correspondence (116 letters between 1753 and 1789) with the Berlin theologist, philosopher, and historian Jean H.S. Formey (1711-1797), contributor to Encyclopédie (Diderot, d’Alembert) and member of the Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften. Fermin dedicated his first book to him, adding, “Depuis ma plus tendre jeunesse vous m’avez honoré d’une protection aussi constante qu’efficace; je n’ai cessé d’en ressentir les salutaires effets …,” which translates to, “Since my tender loving youth, you have honored me with a continuous, as well as efficacious protection; I have experienced the salutary effects continuously” (Traité, 1764; fig. 1). He often asked him for letters of recommendation or merchandise that was lacking in Surinam. He married the widow of a well-to-do apothecary, Maria Magdalena Morin, and became a person of good report. Although it is unknown how he managed to do so, he obtained a degree, probably a doctorate honoris causae, from the University of Aberdeen in 1758. Meanwhile, he observed and described flora and fauna and sent specimens of the local flora and rare insects to the Akademie in Berlin. After an eight-year stay in Paramaribo, he had made a good deal of money, more than 20,000 florins, which is more than his fellows would have at the end of their lives. He estimated the sum to carry interest rates to live decently. He and his wife departed for the Netherlands on May 5, 1762. Upon arrival in the Netherlands, he settled in Maastricht and published a number of books. He was considered a specialist in natural history of equatorial America.

Treatise on the Most Frequent Diseases in Surinam

His first book, Traité des Maladies les Plus Fréquentes à Surinam et des Remè des les Propres à les Guérir, which translates to The Most Frequent Diseases in Surinam and the Appropriate Remedies to Treat Them, was published two years after returning from Surinam (1764). In the introduction, he wrote: “Un Médecin nouvellement débarqué dans ce Païs, a deux choses principales à faire. La première, c’est d’observer avec la derniè

re exactitude la Nature du Climat & les variations qui influent si considérablement sur l’état des corps & sur l’effet des remèdes …” or “A physician recently arrived in that country, has two principle things to do. The first is to observe the nature of the climate with the greatest accuracy and the changes that influence the state of the body in a considerable way and the effects of the remedies …” He opined that many diseases of the people living in Suriname, Creols, as well as Europeans, resulted from excesses of debauchery.

Neurological Disorders

Fig. 2. Title page of his Description Générale (1769)

Several neurological disorders were described in his Traité, although the author sometimes had problems making a diagnosis. In a chapter named “De la Fiè

vre Ardente” (“Burning Fever,” possibly American typhus or yellow fever), he described an often mortal disease accompanied by heat, thirst, nausea, anxiety, insomnia, vomiting, delirium, coma, and convulsions. Pain was felt in the region of the stomach. Fermin prescribed bloodletting, as well as all kinds of drugs, including cort. Peruvian (Peruvian bark, cinchona) and Sem. Papaver (semillas de papaver, or seed of papaver for insomnia). Another disease, known as “klem” (grip), Fermin believed, resembled apoplexy, as well as catalepsy, but more probably he thought it was “tetanos.”

In a chapter named “Du Boisi,” he described leprosy as, “Quand cette Maladie qui peut durer dix, vint, jusqu’à trente ans, est une fois parvenue à son plus haut degré, les doigts et les orteils se détachent insensiblement d’eux-màªmes, sans que le Malade en soie douloureusement affecté,” meaning “When that malady that may last 10, 20, up to 30 years, has reached its highest degree, the fingers and toes come off insensibly, without the patient being painfully affected. It has a poor prognosis, he writes. “Cette horrible Maladie est absolument incurable. Elle n’est pas fréquente parmi les blancs, mais elle attaque souvent les Esclaves.” It translates to “That horrible disease is absolutely incurable. It is not frequent among the whites, but it often attacks the slaves.” The disease was considered contagious and could become epidemic. A patient would be indicated a place in the woods, where he had to end his days without any communication with the others. Fermin himself had learned to distinguish the spots of leprosy from those of other skin diseases, like “ringworm” (tinea), through a lesson from “une vieille Négresse” — stick a needle into the spot while pinching it; if it is insensible, then it’s leprosy.

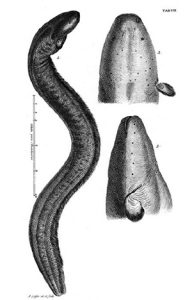

Fig. 3. Trembling eel from Gronov’s Zoophylacium (1758)

Another chapter (no. 9 “Du beillac”) is of neurological interest. The name derives from the Creol or original inhabitants, Fermin believed. It was associated with the work of the devil because of the severe colic pain. He believed it was nothing else than the well-known “colica pictonum” (an affliction known since the Roman Empire, of which it was assumed later that it was due to chronic lead intoxication; the lead was used to sweeten the wine). However, the Surinam beillac was more severe, Fermin opined, and was caused by immoderateness (drink, lack of sleep). He thought it should not be confused with other types of colic and believed it was often treated in the wrong way, leading to paralysis or death. He presented a long list of drugs and regimens to apply. The combination of colic pain and paralysis could indeed fit a chronic lead intoxication, particularly when the term colica pictonum was used. Today we could also think of Guillain-Barré syndrome preceded by an infectious bowel disease and porphyria, although intermittent disease would be expected in the latter. However, we have to be careful with making retrospective diagnoses. Furthermore, it is important to realize that, at the time, differences in diseases across the world were believed to be of degree, not of kind. Humidity, fluctuating and high temperatures, and the sun were considered the most important factors to weaken the Europeans, increasing their vulnerability to disease. The pathophysiology was still humoral and mentioned conditions were thought to cause unbalance of the humors.

One year after his Traité, Fermin published Histoire Naturelle de la Hollande Equinoxale ou Description des Animaux, Plantes, Fruits et Autres Curiosités Naturelles, que se Trouvent Dans la Colonie de Surinam Avec Leurs Noms Différents Tant François que Latins, Hollandois, Indien et Nègre-Anglois, which translates to Natural History of Equatorial Holland or Description of Animals, Plants, Fruits and Other Natural Curiosities, that are Present in the Colony of Surinam With Their Different Names be it French, or Latin, Dutch, Indian and Negro-Anglian (Amsterdam, Magérus, 1765).

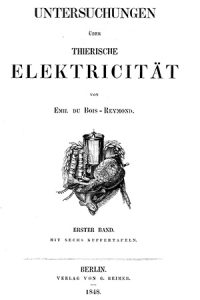

Fig. 4a: Frontispices from Du Bois-Reymond’s volumes depicting a torpedo

In 1768, he published “Instructions Importantes au Peuple sur les Maladies Chroniques. Pour Servir de Suite à l’Avis au Peuple de M. Tissot, sur les Maladies Aiguës.” That translates to, “Important Instructions for the People on Chronic Diseases. To Serve as a Continuation of Advice to the People by Mr. Tissot, on the Acute Diseases.” Indeed, the well-known Swiss physician Samuel Auguste Tissot (1728-1797), author of Traité des Nerfs, had published his “Avis au Peuple sur sa Santé, ou Traité des Maladies les Plus Fréquentes,” which translates to “Advice to the People on its Health, or Treatise on the Most Frequent Maladies” in 1761, with several new editions to follow. Tissot’s original purpose had been to publish it as an “ouvrage composé en faveur des Habitans de la Campagne, du Peuple des Villes, et tous ceux que ne peuvent avoir facilement les conseils des Médecins” — “text put together in favor of the inhabitants of the countryside, the people of the cities and those who are not able easily to consult physicians.” Fermin’s first volume contains 20 chapters on anatomical subjects; the second volume contains 58 chapters on diseases and surgical subjects. About 14 of these deal with neuropsychiatric subjects, including tremor, spasm, catalepsy, melancholia, mania, headache, speechlessness, and memory loss.

In 1770, Fermin pleaded for better treatment of the slaves in his “Dissertation sur la Question: S’il est Permis d’Avoir en sa Possession des Esclaves et de s’en Servir Comme tels dans les Colonies de l’ Amérique,” which translates to “Dissertation on the Question: Is it Allowed to Keep Slaves in One’s Possession and Make Use of Them in the Colonies of America.”

Trembling Eel

Fermin’s “Histoire Naturelle” of 1765, mentioned earlier, was later augmented and published in two volumes Description Générale (Amsterdam, Van Harrevelt, 1769; fig. 2), which were translated into German and Dutch. At least one part of this book is of neurological interest, notably where he described the trembling eel (fig.3). This animal had been of interest, in particular during the 18th and 19th centuries, and was studied by colonists as well as scientists in Europe. “If one touches it with the hand or a stick, it causes an involuntary or forced trembling, resembling the vibration.” Fermin was able to keep the fish alive in a tub for six weeks and showed a keen interest on electric transmission of potentials from one person to another.

Fig. 4b: A horse brought down by the discharge of an electric eel

He described the numbness being felt in the arms up to the shoulders and in the legs when the fish touched his hand or foot. He intended to further investigate the fish, but the heat of the country prevented him to completely dissect the animal. However, he observed two muscles that were distinct from the other muscles. He supposed that these were the principal instruments of the trembling. Indeed, it was in 1776 that the electric nature of the fish was proved at the Royal Society (London) by drawing sparks. At the time, the ability to produce a spark was considered a fundamental criterion for something to be electrical in 18th century science. These and other observations influenced Luigi Galvani, when he described animal electricity (finding Alessandro Volta as his opponent). About half a century later, the Berlin physiologist Emile du Bois-Reymond proved the electric nature of nerves by discovering the action potential (figures 4a and b).

Fermin kept on writing about his observations and published another extension of his 1769 Description Générale in 1776, “Tableau Historique et Politique de l’état Ancien et Actuel de la Colonie de Surinam et des Causes de sa Décadence,” (Maastricht, Dufour and Roux), which translates to, “Historical and Political Depiction of the Ancient and Actual State of the Colony of Surinam and the Causes of its Decline.” It was translated into German in 1778 and English in 1788.

During the last decades of his life, Fermin served as juror and alderman in the city of Maastricht, and, when the Netherlands were under French rule (1795-1813), he became judge of the civil court of justice, and from 1803 a substitute judge at the Cour Criminelle.

This is a comprehensive, extremely well-written, single-author textbook on emergency and critical care neurology by one of the most renowned, experienced, published, and respected neurointensivists. In his preface to this second edition, the author outlines his intention for this book to serve as a practical and data-driven guide to management of the critically ill neurological patient, rather than a textbook detailing theory. This is exactly how I perceived this book. It is organized into 12 chapters that include a symptoms-based approach, organizational aspects, general critical care aspects, and management of specific disorders, complications, or consultation situations. Some of the chapters are geared more toward the neurologist assessing emergent consultation, some to the neurologist or neurointensivist managing the specific neurocritical disorders, and some to the neurointensivist or critical care physician staffing an intensive care unit. Complex topics and concepts are presented in a clear and concise manner, and enhanced by plenty of original illustrations and imaging examples. The text is supported by available, up-to-date data, as well as the vast clinical experience of the author himself. Sensitive topics, such as end-of-life discussions or ethical dilemmas, are addressed with vision and care. The statements are clear with virtually no redundancy or ambiguity. Flow is excellent, and style and organization allow for both rapid, continuous reading, as well as rapid look-up.

This is a comprehensive, extremely well-written, single-author textbook on emergency and critical care neurology by one of the most renowned, experienced, published, and respected neurointensivists. In his preface to this second edition, the author outlines his intention for this book to serve as a practical and data-driven guide to management of the critically ill neurological patient, rather than a textbook detailing theory. This is exactly how I perceived this book. It is organized into 12 chapters that include a symptoms-based approach, organizational aspects, general critical care aspects, and management of specific disorders, complications, or consultation situations. Some of the chapters are geared more toward the neurologist assessing emergent consultation, some to the neurologist or neurointensivist managing the specific neurocritical disorders, and some to the neurointensivist or critical care physician staffing an intensive care unit. Complex topics and concepts are presented in a clear and concise manner, and enhanced by plenty of original illustrations and imaging examples. The text is supported by available, up-to-date data, as well as the vast clinical experience of the author himself. Sensitive topics, such as end-of-life discussions or ethical dilemmas, are addressed with vision and care. The statements are clear with virtually no redundancy or ambiguity. Flow is excellent, and style and organization allow for both rapid, continuous reading, as well as rapid look-up.

Neurological disease has increased its burden over the world population. Naturally, the Pan American community is no exception. There are some particular situations in different areas— infectious and parasitic disease are still everyday events in some areas, malnutrition and metabolic in others, children with sequelae of difficult pregnancies and deliveries are prevalent in some communities, but the frequent pathologies of the nervous system are similar in all of our countries. Cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, developmental difficulties, headaches, and behavioral syndromes have a very similar prevalence. Increases in communication and migration have also contributed to provide a more universal panorama of illness. And, of course the appearance of new threats like Zika virus has swiftly become a multinational preoccupation.

Neurological disease has increased its burden over the world population. Naturally, the Pan American community is no exception. There are some particular situations in different areas— infectious and parasitic disease are still everyday events in some areas, malnutrition and metabolic in others, children with sequelae of difficult pregnancies and deliveries are prevalent in some communities, but the frequent pathologies of the nervous system are similar in all of our countries. Cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, developmental difficulties, headaches, and behavioral syndromes have a very similar prevalence. Increases in communication and migration have also contributed to provide a more universal panorama of illness. And, of course the appearance of new threats like Zika virus has swiftly become a multinational preoccupation.

There were very few aspects of the book that disappointed me as a reader who specializes in care of pediatric neuromuscular disorders, and none were overly striking. While all figures are interpretable regarding what they are meant to illustrate, many of the pathology figures in particular would be much better appreciated in color rather than the black and white version in the text. A color section of the text or an online color supplement would greatly augment the reader’s appreciation of the beautiful examples selected for presentation regarding the pathology of DMD. The recommendation to perform muscle biopsy in every patient for direct dystrophin studies, in addition to molecular genetics, is somewhat strongly worded for the current practice of most of today’s neuromuscular clinics. However, the authors do temper this by emphasizing in other sections of the text the particular populations where this can be especially useful, such as a young patient with an identified dystrophin gene mutation which has previously been reported as having variable phenotypic expressions. It is also easily appreciated that the multi-systemic management issues in older Duchenne patients are complex: in the text, topics such as spinal surgery and cardiopulmonary management are dealt with rather briefly, in contrast to the more extensive discussion of musculoskeletal management of the ambulant child with DMD, for example. These are all minor points, and none was jarring enough to detract from the book’s many admirable qualities.

There were very few aspects of the book that disappointed me as a reader who specializes in care of pediatric neuromuscular disorders, and none were overly striking. While all figures are interpretable regarding what they are meant to illustrate, many of the pathology figures in particular would be much better appreciated in color rather than the black and white version in the text. A color section of the text or an online color supplement would greatly augment the reader’s appreciation of the beautiful examples selected for presentation regarding the pathology of DMD. The recommendation to perform muscle biopsy in every patient for direct dystrophin studies, in addition to molecular genetics, is somewhat strongly worded for the current practice of most of today’s neuromuscular clinics. However, the authors do temper this by emphasizing in other sections of the text the particular populations where this can be especially useful, such as a young patient with an identified dystrophin gene mutation which has previously been reported as having variable phenotypic expressions. It is also easily appreciated that the multi-systemic management issues in older Duchenne patients are complex: in the text, topics such as spinal surgery and cardiopulmonary management are dealt with rather briefly, in contrast to the more extensive discussion of musculoskeletal management of the ambulant child with DMD, for example. These are all minor points, and none was jarring enough to detract from the book’s many admirable qualities.