Delegates and staff of the Dakar Conference on the formation of CAA. Paul Kioy, Anthony Zimba, Gallo Diop, Lionel Carmant, Calixte Kuate, Sokhna Ba, Mansour Ndiaye, Mareme Sene, Nico Moshe, Late Bryan Kies, Birinius Adikaibe, Emilio Perruca, Pierre-Marie Preux, Baba Koumare, Sammy Ohene, Amara Cisse, Michel Baulac, Sam Wiebe.

By Dr. Ezeala-Adikaibe Birinus

The enormous challenges facing epilepsy care in Africa, especially in poor and rural areas, cannot be overemphasized. All human development indicators, despite some improvement, remain low and unacceptable. Faced with other pressing issues and social conflicts, bringing epilepsy to the forefront has been an uphill task. In recent years, the number of training institutions for doctors and nurses has increased and more qualified personnel in the area of neurological disorders have been trained. The number of diagnostic equipment and specialist centers for neurological diagnosis has grown. However, for a reasonable impact to be made, efforts geared toward increasing awareness, advocacy, reducing the price of medications and improving access to care and research to a more coordinated approach are required.

To achieve these aims, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) set up the Commission on African Affairs in 2010 in Dakar, Senegal.

The official inaugural meeting of the African commission of ILAE took place in November 2010. The parent body, ILAE, convened, and Prof. Amadou Gallo Diop of Senegal and Senegalese League Against Epilepsy served as a facilitator.

Representatives from the following countries were present: Dr. Calixte Kuate-Tegueu (Cameroon), Dr. Sammy Ohene (Ghana), Prof. Amara Cisse (Guinea), Prof. Paul Kioy (Kenya), Prof. Baba Koumare (Mali), Dr. Birinus Ezeala-Adikaibe (Nigeria), Prof. Amadou Gallo Diop (Senegal), Dr. Brian Kies (South Africa) and Dr. Angelina M Kakooza (Uganda).

ILAE delegation was led by Prof. Solomon Nico Moshe (President, U.S.), Prof. Emilio Perucca (Treasurer, Italy), Prof. Sam Wiebe (SecretaryGeneral, Canada), Prof. Michel Baulac (Second Vice President, France) and Prof. Lionel Carment (Canada). Invited observers were Prof. Alfred Njamnshi (President of Pan African Association of Neurological Sciences, Cameroon), Prof. Pierre-Marie Preux (Tropical Neurological Institute of Limoges, France) and Dr. Anthony Zimba (IBE Africa Commission, Zambia).

Prof. Mansour Ndiaye, head of the Department of Neurology of the University of Senegal, read a welcome address. Prof. Solomon Moshe followed and talked about the history of African Commission, including failures and challenges. The present and past efforts of the country’s Leagues Against Epilepsy were discussed in presentations.

Carmant, Wiebe and Preux made presentations, showing the great opportunities and prospects of working as a team to develop the African Commission. It was noted that a lot of work has been done or is presently going on in various parts of the continent, but there is a need for proper coordination and collaboration.

The second day of the meeting was dedicated to the formation of the commission (ILAE-CAA). The executive members of ILAE emphasized the benefits of working as a team and the successes achieved in other regions of the world and the scope of the future CAA based on ILAE bylaws.

Moshe encouraged the African Commission to move forward and work as a team despite the envisaged challenges. He urged them to call on the parent body for help when the need arises. He said the North American Commission is looking forward to building a partnership in Africa to promote the treatment of epilepsy and research into newer epilepsy syndromes.

Later in the day, the potential members of CAA discussed and elected the officers that will run the commission until 2015. The officers were selected (see below) and were later endorsed by the international executive. Further work was done in setting out the commission’s Action Plan for 2011-2015.

Delegates and staff of the Dakar Conference on the formation of CAA are Paul Kioy, Anthony Zimba, Gallo Diop, Lionel Carmant, Calixte Kuate, Sokhna Ba, Mansour Ndiaye, Mareme Sene, Nico Moshe, Late Bryan Kies, Birinius Adikaibe, Emilio Perruca, Pierre-Marie Preux, Baba Koumare, Sammy Ohene, Amara Cisse, Michel Baulac, Sam Wiebe.

The commission’s task was to consolidate gains and create awareness of epilepsy and related disorders. Every avenue should be used, including newspapers, radios, television and community-based programs.

Goals of the Commission

- To set up the organization of the newly formed Commission on African Affairs (CAA)

- To strengthen the communication and ILAE global outreach campaign of the CAA

- To establish and strengthen the education activities of the CAA

- To improve the access to care for patients with epilepsy

- To establish and coordinate epilepsy-related research activities in the African continent

- Work with pharmaceutical companies on programs that at term will help to lower the cost of main drugs and provide better access to care for people with epilepsy in Africa

- Provide the list of epilepsy training centers in Africa and organize the visiting professorship in these centers

- Set up biannual training courses in the two main foreign languages used in Africa: French and English

Achievement of the Commission 2010-2014

- 2011: participation in the meeting of the task force on distance education (Brussels, Belgium)

- Commission meeting. Since its inception, the commission has had three meetings: Rome (2011), Nairobi (2012) and Montreal (2013). All meetings were held either during the International Epilepsy Congresses or African Epilepsy Congress

- Organization of the first African Epilepsy Congress (June 21-23, 2012, in Nairobi, Kenya)

- Organization of the second African Epilepsy Congress (May 22-24, 2014, in Cape Town, South Africa).

- Organization of regional training courses. (June 20, 2012, during the first African Epilepsy Congress in Nairobi)

- Enhancement and promotion of the use of online training courses for health workers in the continent (VIREPA courses)

- Increase in the number of chapters from 12 to 16. Burkina Faso, Cote D’Ivoire and Congo Democratic Republic were re-activated

- Publication of the regional newsletter

Work in Progress

- Epilepsy training courses will be organized in French, English and Portuguese.

- Provide the list of epilepsy training centers in Africa and organize the visiting professorship in these centers.

Consistency and feasibility of ideas remain the goal of commission.

(ILAE/IBE member countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Congo Democratic Republic, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe)

Birinus is the communication officer for the Commission on African Affairs, International League Against Epilepsy.

Due to differences in their philosophies, the two societies were effectively in competition, resulting in what many European neurologists concluded was an unnecessary duplication of effort. The initial event of their coming together was the creation of the European Board Examination in Neurology, where the examination’s creator, the UEMS – European Board of Neurology (

Due to differences in their philosophies, the two societies were effectively in competition, resulting in what many European neurologists concluded was an unnecessary duplication of effort. The initial event of their coming together was the creation of the European Board Examination in Neurology, where the examination’s creator, the UEMS – European Board of Neurology (

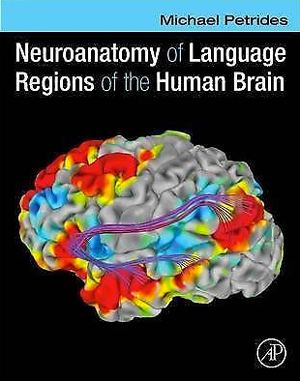

The human brain contains billions of neurons, and these neurons interact in a variety of ways that are only beginning to be understood. One of the great challenges that humans confront is determining the way in which the human brain can support complex behaviors such as reading and understanding this text. We can begin to confront this challenge by improving our understanding of human neuroanatomy.

The human brain contains billions of neurons, and these neurons interact in a variety of ways that are only beginning to be understood. One of the great challenges that humans confront is determining the way in which the human brain can support complex behaviors such as reading and understanding this text. We can begin to confront this challenge by improving our understanding of human neuroanatomy.