By Donald Silberberg, MD

Donald H. Silberberg

Two remarkable meetings took place in March in Durban, South Africa. On March 25, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U.S.) convened a workshop on implementation science, that is, how to use research findings, whether epidemiologic, basic science, clinical or economic studies, to influence public policy. In a previous editorial, I referred to this as “translational research,” the concept of moving from research data to utilization.

Investigators supported by the Fogarty International Center (FIC), NIH, presented the results of studies that are beginning to achieve this, in Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia. Discussion centered on both impediments in achieving implementation, and on what has worked in some locales. All of the presenters and discussants agreed that further efforts are needed to develop approaches that will use research findings to improve neurologic and psychiatric health in every country, and the need to provide this information to all investigators in low- and middle- income countries. Interested investigators should watch for future notices from the FIC.

The NIH workshop was followed by the 12th International Conference of the Society of Neuroscientists of Africa (SONA). In addition to basic and clinical neuroscience presentations by invited speakers from Italy, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, the U.K. and the U.S., investigators from all regions of Africa presented 157 posters and platform talks. At least half of these dealt with clinically relevant topics, ranging from studies of trypanosomiasis in the DRC, to pain following traumatic spinal cord injury in Zimbabwe. The abstracts can be viewed at www.sona2015.com. The next meeting, in 2017, will be held in Uganda. This meeting is clearly designed to include clinical neurologists as well as neuroscientists.

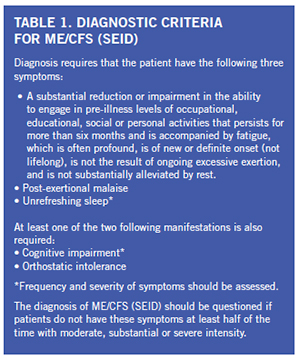

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.

We recognize that English is not the native language of many of our authors, and we will allow re-submission of manuscripts that require editing. My suggestion for authors is to have their manuscripts edited by someone who has excellent command of the English language. If you do not have ready access to such a person, please utilize one of the many excellent “English editing” services. In fact, Elsevier will provide this online service to authors for a modest fee.

We recognize that English is not the native language of many of our authors, and we will allow re-submission of manuscripts that require editing. My suggestion for authors is to have their manuscripts edited by someone who has excellent command of the English language. If you do not have ready access to such a person, please utilize one of the many excellent “English editing” services. In fact, Elsevier will provide this online service to authors for a modest fee.

The European Board Examination in Neurology is a joint development of the UEMS Section of Neurology and the European Academy of Neurology. It is considered to be a tool for the assessment of European neurological education and to boost its European standards.

The European Board Examination in Neurology is a joint development of the UEMS Section of Neurology and the European Academy of Neurology. It is considered to be a tool for the assessment of European neurological education and to boost its European standards. The European Board Examination in Neurology is a substantial step forward in the further harmonization and in the raising of the standards in European neurology. The cooperation with the scientific neurological societies is an important scientific input and a guarantee of continuous updates of the current knowledge of a European neurologist.

The European Board Examination in Neurology is a substantial step forward in the further harmonization and in the raising of the standards in European neurology. The cooperation with the scientific neurological societies is an important scientific input and a guarantee of continuous updates of the current knowledge of a European neurologist.