Figure 1. Rembrandts Anatomical Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632); © Mauritshuis, The Hague.

A centuries-old mystery shrouds a renowned painter and his imagination.

By Peter J. Koehler

The Dutch physician and mayor of Amsterdam Nicolaes Tulp (1593-1674) is known for being depicted in the 1632 painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). (See Figure 1.) The criminal Aris’t Kint, the person on whom an autopsy is performed in the painting, was sentenced to “punishment with the cord,” which was carried out on Jan. 31 of that year. His corpse was made available to the Amsterdam surgeons’ guild, of which Tulp was praelector anatomiae, a term the guild used for anatomy instructors. Tulp had already been in contact several times with the 26-year-old Rembrandt to discuss a painting of an anatomy lesson. In his composition, Rembrandt broke with the traditions of the group portrait for the time.1

Figure 2. Tulp’s Observationes Medicae (second edition 1652).

Observationes Medicae (1641)

Tulp studied medicine at Leiden University and settled in Amsterdam. He chose his surname from the tulips that graced the facade of his house. He was the first Amsterdam physician to visit his patients by coach. One of his contemporaries described him as an intelligent and capable man, with a practice large enough “so that it was necessary to drive a coach … having prepared a place in the cellar under his house …”

His Observationes Medicae was published in 1641 and contained three books. The second edition, published in 1651, contained four books and 233 cases. (See Figure 2.) Many editions followed as the work was popular and praised by many, including the Swiss physician Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777). Some of the neurological cases in Observationes Medicae have been discussed in recent medical literature. These include spina bifida,2 cluster headache,3 head injury4 including a case with a depressed fracture for which the trepan was applied, cerebral hemorrhage, beri-beri (polyneuropathy that is now known to be caused by thiamine deficiency), hydrocephalus, diastematomyelia, posttraumatic amnesia,5 and several types of tremors.6

Figure 3. Thijssen’s second dissertation dedicated to Charcot (1888).

Traumatic Hysteria

There is an interesting case from Tulp’s book that was referred to by the Dutch physician Eduard Hendrik Marie Thijssen (1856-1932), but it has not been discussed in more recent history.

Thijssen was the son of Amsterdam professor of medicine Henricus Franciscus (1820-1915). After studying medicine, young Thijssen defended his dissertation on Nicolaes Tulp in 1881.7 He settled in Paris, where he was taught by Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) at the Salpêtrière.

Like his grandfather Henricus Franciscus Thijssen (1787-1830), who also published on hysteria, Eduard Thijssen had a special interest in this condition. He wrote a second dissertation, Contribution à l’étude de l’hystérie traumatique (1888), which he dedicated to “Mon cher et vénéré maitre M. le Professeur Charcot” (My dear and revered master Professor Charcot). (See Figure 3.) In this dissertation, he mentioned an interesting case, which he had read in Tulp’s Observationes, of “a famous painter of Rembrandt’s time (perhaps even Rembrandt himself), who was bedridden for an entire winter with mental paralysis of the legs.”8

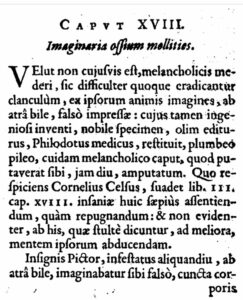

Figure 4. Chapter 18 of Tulp’s Observationes on Imaginaria ossium mollities (Imagined softness of the bones).

Melancholy

In Chapter 18 of the first book of Tulp’s Observationes Medicae, we indeed find the case with the title “Imaginaria ossium mollities” or “Imagined softness of the bones.” (See Figure 4.) Tulp introduced his case with information on diseases caused by “atra bile” (literally “black bile” which at the time was thought to cause melancholy) and imagined symptoms.

Tulp referred to “the ingenious invention of Philodotus Medicus” for treating a melancholic king, who imagined his head had been cut off. Philodotus put a leaden hat on the king’s head. The weight of the hat made the king think that he had recovered his head, so that he was free from his delusion.

The case has been referred to by many scholars, including English author Robert Burton (1577-1640) in his famous Anatomy of Melancholy of 1621.9 (See Figure 5.) Not much has been discovered about Philodotus since the anecdote was first published by Alexander of Tralles (c. 525- c. 605).10

With respect to the treatment of such patients, Tulp also referred to the Roman encyclopedist Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BCE – c. 50 CE), who wrote in his famous De Medicinae “… in others, melancholy thoughts are to be dissipated, for which purpose music, cymbals, and noises are of use. More often, however, the patient is to be agreed with rather than opposed, and his mind slowly and imperceptibly is to be turned from the irrational talk to something better.”11

Figure 5. Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, in which he referred to Philodotus’ case.

Softness of the Bones

Tulp described his own patient as “Insignis Pictor infestatus aliquandiu, ab atrâ bile” or “a renowned painter, plagued for some time with the black bile.” The patient imagined that the bones of his body were so soft and pliable that they would easily fold if he put the slightest pressure on them.

“Which imagination being deeply engraved in his soul, kept himself in bed a whole winter; fearing, when he arose from it, of some calamity, which was more certain than certain to befall him, which he had hitherto dreaded, a deformity of his legs, or rather of his whole body,” Tulp wrote.

Understanding the patient’s fear, Tulp did not want to oppose him. He visited him secretly to slowly ease his imagination, assuring him that this softness was not unknown to physicians. Here he referred to De abditis rerum causis (Of the hidden causes of things; 1548) by the French physician Jean François Fernel (1497-1558), who introduced the term “physiology.”

Tulp told the painter that as wax can be made soft and hard, medicine could do the same in his legs. Tulp said that within three days the painter’s legs would be restored to their former firmness, and by the sixth day, he would have the ability to go anywhere, but only if he listened to Tulp’s advice.

“One can hardly say, how great hopes these promises raised to regain health, and how obedient they made him, to use the remedies prescribed for the black bile. Which being duly driven from the body, we were easily able to keep our word, ordering him to rise from the bed in which he had lain a whole winter,” Tulp wrote.

At first, the painter was told to stand on his feet and not allowed to walk. He would not have permission to go where he wished until the sixth day. “But the sixth day now approaching, we showed openly the truth of our promise: giving him not only freedom to walk about the room, but also to appear in public, and to perform all the activities of a healthy man at once.” Tulp concluded by wondering how this painter had not been able to see that the inability to walk, which had kept him in bed all winter, had only been in his imagination, although he was otherwise a great craftsman, “having scarcely anyone equal to him.”12

Figure 6. Portrait of Nicolaes Tulp by Frans Hals (1633); © Collection Six, Amsterdam.

Who Was This Painter?

The question now is, which “renowned painter” had Tulp been secretly treating? In other cases he described in his book, he often provided the full name of his patients, as in the case of cluster headache in the 13th chapter of the first book: Isaak van Halmaal.3 He must have seen the patient between 1614, the year in which he obtained his MD, and 1641, the year in which Observationes Medicae was published.

Could it have been one of the painters who did a portrait of Tulp? There were at least six painters who did, including Frans Hals (1580-1666; see Figure 6), Cornelis van der Voort (1576-1624), Adriaen Cornelisz Beeldemaker (1620-1709), Jurgen Ovens (1623-1678), Nicolaes Eliasz Pickenoy (1588-1650/6), and the aforementioned Rembrandt van Rijn. If it was one of these six painters, which one was famous in the 1630s and suffered from melancholy or depression?

Figure 7. The expensive house Rembrandt bought in 1639, presently Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam.

Retrospective diagnoses are always hazardous. Several physicians have written about depression that would have been recognizable in Rembrandt. One author wrote that he was depressed, as seen in several of his many self-portraits,13 but he was contradicted by a critic.14 Yet another wrote about “Rembrandt’s metaphoric portrayal of the depressed mind” in reference to his etching of Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber in 1642, the year in which his wife Saskia van Uylenburgh died.15 This was a year after Tulp published his Observationes.

In 1640, Rembrandt’s mother died and prior to that his first three children died.15,16 In 1639, he bought the expensive three-story house on St. Anthony Breestraat (today’s Rembrandt House Museum) and received the commission for The Night Watch (1642), on which he would work for three years. (See Figure 7.) One of his biographers, art historian Jakob Rosenberg (1893-1980), used the term “crisis” in reference to this period of his life.17

As Tulp visited his patient secretly and did not mention him by name in his case description, we will probably never be sure about the identity of the painter, but it could have been Rembrandt van Rijn. •

References

1. Keeman JN. Nicolaes Tulp en het Amsterdame chirurgijnsgilde. In: Beijer T et al. Nicolaes Tulp. Leven en -werk van een Amsterdams geneesheer en magistraat. Amsterdam, Six Art Promotion bv, 1991, pp. 157-83.

2. Koehler PJ. Chiari’s description of cerebellar ectopy (1891). With a summary of Cleland’s and Arnold’s contributions and some early observations on neural-tube defects.

J Neurosurg. 1991 Nov;75(5):823.

3. Koehler PJ. Prevalence of headache in Tulp’s Observationes Medicae (1641) with a description of cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 1993 Oct;13(5):318-20.

4. Kompanje EJ, Maas AI. ‘De dreuning der daverende hersenen’; behandeling van traumatisch schedel-hersenletsel in Nederland in de 17e eeuw: 7 ziektegeschiedenissen uit Observationes medicae van Nicolaes Tulp [‘The rumbling of shaking brains’; the treatment of traumatic skull and brain injury in the Netherlands in the 17th century: 7 case reports from Observationes medicae by Nicolaes Tulp]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2004 Apr 3;148(14):677-82.

5. Koehler PJ. Neurology in Tulp’s Observationes Medicae. J Hist Neurosci. 1996 Aug;5(2):143-51.

6. Koehler PJ, Keyser A. Tremor in Latin texts of Dutch physicians: 16th-18th centuries. Mov Disord. 1997 Sep;12(5):798-806.

7. Thijssen EHM. Nicolaas Tulp als geneeskundige geschetst: eene bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der geneeskunde in de XVIIde eeuw. Amsterdam, Schröder, 1881.

8. Thijssen EHM. Contribution à l’étude de l’hystérie traumatique. Paris: Imprimerie de la Faculté de Médicine, Davy, 1888.

9. Burton R. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Part 2, Section 2. Philadelphia, Wardle, p. 448.

10. Smith W. Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. III. Boston, Little & Brown, 1849, 304.

11. Celsus. De Medicinae. New York, The Classics of Medicine Library. 1989, p.295.

12. Tulp N. Observationes Medicae second edition. Amsterdam, Elsevirium, 1652.

13. Espinel CH. Depression, physical illness, and the faces of Rembrandt. Lancet. 1999 Jul 17;354(9174):262-3.

14. Rothenberg A. Depression, physical illness, and the faces of Rembrandt. Lancet. 1999 Oct 16; 354(9187):1392.

15. Schildkraut JJ. Saint Jerome in a dark chamber: Rembrandt’s metaphoric portrayal of the depressed mind. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;161(1):26-7.

16. Schildkraut JJ, Cohn MB, Hawkins H. Then melancholy, now depression: a modern interpretation of Rembrandt’s mental state in midlife. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007 Jan;195(1):3-9.

17. Rosenberg J. Rembrandt. His life and work. Rev. Edition. Ithaca (NY), Phaidon, 1964, p. 23.