By Douglas J. Lanska

Douglas J. Lanska

In the late 1860s, on the basis of his clinical and anatomical studies, Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) concluded preliminarily that leprosy was a distinct disease with a specific cause, and not simply a degenerative condition with multiple potential etiologies. (See Figures 1 and 2.) His subsequent epidemiological studies in Norway found no association between the occurrence of leprosy in various districts and general mortality rates, provided evidence that leprosy was contagious rather than hereditary, and demonstrated that isolation of cases produced a decline in incidence.

In 1873, Hansen discovered rod-shaped bodies — Mycobacterium Leprae, sometimes called Hansen’s bacillus — in leprous nodules, although he did not clearly identify them as bacteria. He described these in a report to the Medical Society of Christiania (now Oslo) and in his main treatise in 1874, with a shorter English version in 1875:

Figure 1. Gerhard Armaner Hansen. Photograph by J.F. Lehman, Munich, 1912. Public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

“While leprosy may be … indirectly proved to be a specific disease by demonstrating its contagiousness, it would, of course, be the best if a direct proof could be given. I will briefly mention what seems to indicate, that such proof is, perhaps, attainable. There are to be found in every leprous tubercle extirpated from a living individual — and I have examined a great number of them — small staff-like bodies, much resembling bacteria, lying within the cells; not in all, but in many of them. Though unable to discover any difference between these bodies and true bacteria, I will not venture to declare them to be actually identical. Further, while it seems evident that these low forms of organic life [i.e., bacteria] engender some of the most acute infectious diseases, the attributing of the origin of such a chronic disease as leprosy to the apparently same matter must, of course, be attended with still greater doubts. It is worthy of notice, however, that the large brown elements found in all leprous proliferations in advanced stages … bear a striking likeness to bacteria in certain stages of development … .”

Figure 2. A 24-year-old Norwegian man with lepromatous leprosy. From Leloir H. Traité pratique et théorique de la lè

pre. Paris: A. Delahaye et Lecrosnier. 1886. This figure was later reprinted by Hansen in his monograph (1895). Public domain. Courtesy of the Bibliothè

que nationale de France.

Hansen tried unsuccessfully to stain his preparations. In 1879, when Hansen was visited by Albert Neisser (1855-1916), a young colleague from the laboratory of German physician and pioneering microbiologist Robert Koch (1843-1910) in Breslau, Hansen, encouraged him to try to stain the bacteria. (See Figure 3.) Shortly after Neisser returned to Breslau, he succeeded in staining the bacteria, and then promptly announced his findings, suggested that these bacteria were indeed the infectious agent of leprosy, and claimed priority for the discovery.

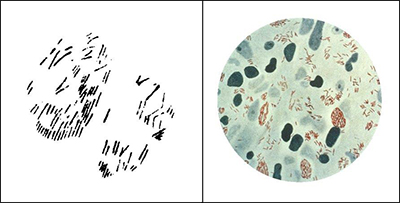

Hansen replied quickly and tried to assert his own priority, and by 1880 he had also succeeded in staining the bacteria. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 3. Albert Neisser. Public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

“It was not my intention to make any of my investigations on this subject public at present, but as not only Dr. Edlund to whom in the preceding year I showed preparations, and mentioned that I considered leprosy a parasitic disease, in his little work on ‘Leprosy’ speaks of its precise origin as something that he has discovered in the form of “micrococci,” by also Dr. Neisser, of Breslau, who passed some portion of this summer in Bergen has just published the result of his investigations of those preparations that he made while here, and as these results also point out that in general, the preparations are filled with ‘bacilli’ which he supposes to be peculiar to leprosy, and as its ‘contagium’— I feel myself called upon to announce what I have attained to, up to the present time, in my researches after the same ‘contagium,’ and, this, partly to assert my priority with reference to this discovery, and partly in order to advance those details in research which I omitted to announce on account of the still uncertain result in my report to the Medical Society of Christiania [Oslo], 1874, concerning my investigations into the etiology of leprosy.”

Figure 4. Left: Hansen’s drawing (1880) of “brown elements colored with methyl violet, from a tubercle treated with osmic acid.” From Hansen (1880). Right: A photomicrograph of Mycobacterium Leprae (small red rods), taken from a leprosy skin lesion. Public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL) #2123.

Although an international consensus generally favored Hansen in this priority dispute as the discoverer of Mycobacterium Leprae, neither Hansen nor Neisser succeeded in fulfilling Henle’s postulates — the criteria to establish a causative relationship between a microbe and a disease propounded in 1840 by German physician, pathologist and anatomist Jakob Henle (1809-1885):

- The microbe occurs in every case of the disease under circumstances that account for the pathological changes and clinical course of the disease;

- The microbe occurs in no other disease as a nonpathogenic parasite; and

- After being isolated and grown in pure culture in an artificial medium, it can induce the disease in an experimental host. These criteria were later augmented by Koch and subsequently known as the Henle-Koch postulates.

Neither Hansen nor Neisser demonstrated that the bacteria observed in cases of leprosy were specific to that disease, nor was Hansen able to transmit the disease to animals or humans using leprous material from patients. Hence, at the time of the Hansen-Neisser controversy, it remained unproven that leprosy is infectious, despite even an unethical attempt by Hansen to transmit leprosy to a patient without informed consent. Furthermore, to this day Mycobacterium Leprae has not been grown in pure culture in an artificial medium.

References:

- Evans AS. Causation and Disease: The Henle-Koch Postulates Revisited. Yale J.

- Biol Med. 1976;49(2):175-195.

- Fite GL, Wade HW. The Contribution of Neisser to the Establishment of the Hansen Bacillus as the Etiologic Agent of Leprosy and the So-called Hansen-Neisser Controversy. Int J Lepr. 1955;23:418-428.

- Hansen GA. Spedalskhedens Arsager (causes of leprosy). Translation by Pierre Pallamary. Intl J Leprosy 1955;23:307-309.

- Hansen GA. On the Etiology of Leprosy. Br Foreign Medico-chirurgical Rev 1875;55:459-489.

- Hansen A. The Bacillus of Leprosy. Q J Microscopical Sci 1880;20:92-102.

- Hansen GA, Looft C. Leprosy: In Its Clinical & Pathological Aspects. Translated by Norman Walker. Bristol: John Wright & Co., 1895.

- Irgens LM. The Discovery of Mycobacteriom Leprae: A Medical Achievement in the Light of Evolving Scientific Meathods. Am J Dermatopathol 1984;6(4):337-343.

- Vogelsang TM. The Hansen-Neisser Controversy, 1879-1880. Int J Lepr. 1963;31:74-80.

- Vogelsang TM. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen: 1841-1912: The Discoverer of the Leprosy Bacillus. His Life and his Work. Int J Lepr 1978;46:257-332.

- Peter J Koehler is the editor of this history column. He is neurologist at Atrium Medical Centre, Heerlen, The Netherlands. Visit his website at www.neurohistory.nl.