Growing knowledge despite a lack of international cooperation.

Peter Koehler

This column on historical aspects of international relationships in the neurosciences usually deals with forms of international cooperation. Exactly 100 years ago, not only political relations collapsed; scientific relationships followed, even though some scientists hoped that their relations would remain above the cataclysm.

Living in neutral countries (Netherlands and Switzerland), at least two neuroscientists, Cornelis Winkler and Constantin von Monakow, hoped that “we neutral countries are … now in the first place obliged to continue to take care of values of humanity and culture and keep upright the international scientific relationships with all energy” (from their correspondence in November 1914). Only shortly after the beginning of World War I, however, they observed that artists and writers declared support to the German military actions, including Paul Ehrlich, Ernst Häckel, and neurologists Wilhelm Heinrich Erb and Hermann Oppenheim, who had sent back their scientific decorations they had once received from England. Monakow opined that this was an injudicious, unfortunate step, estranging them to international science “that has nothing to do with politics.”

Neurological knowledge, however, kept on growing, simultaneously, but now separately. A striking example was the knowledge of peripheral nerve injuries which had only gradually increased in times of peace, but now, sadly, much faster. During World War I, books on peripheral nerve injuries were published in England, France, Germany and the U.S. Probably the best known book on the subject was written by the French Jules Tinel (1879-1952), who published his Blessures des nerfs in 1916. His book became influential, and within a year, it was translated into English and published in New York.

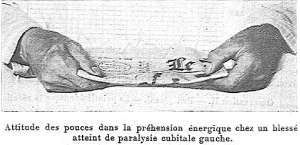

Froment sign (from Presse Médical, Thursday, Oct. 21, 1915)

On the French side, women published on the subject, as is witnessed in Chiriachitza Athanassio-Bénisty, a pupil of Pierre Marie (Paris). She wrote two books with the aim not only to publish the results of clinical experience, but also to improve the quality of examination of peripheral nerve lesions by less experienced physicians. It was translated by Edward Farquhar Buzzard, the English physician, working a.o. at the NationalHospital. From the English ranks, Arthur Henry Evans and James Purves-Stewart published their experiences, largely observations of injured soldiers, many of whom had fought at the various battles near Ypres, Belgium.

From the German side, neurologist/neurosurgeon Otfrid Foerster (1873-1941), who served as an advisory physician to the health office of the VI German Army on the western front in France, gathered abundant information on injuries to the peripheral nervous system and spinal cord. He published his findings in a multivolume handbook of medical experiences from World War I, but also in the supplement to Lewandowsky’s Handbuch der Neurologie, which was entirely devoted to war injuries of the peripheral nerves and spinal cord (single-authored altogether 1,152 pages). In the chapter on surgical therapy of peripheral nerve injuries, he mentioned 4,117 peripheral nerve injuries. Nearly 25 percent underwent surgical procedures, including nerve sutures, nerve transplantations and arm and leg plexus surgeries.

Froment sign (from Presse Médical, Thursday, Oct. 21, 1915).

The U.S. entered World War I in 1917. After submarines sank seven U.S. merchant ships, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson went to Congress calling for a declaration of war on Germany. The U.S. Congress voted on April 6 to do so. Figures with respect to American peripheral nerve injury casualties during World War I were provided by several sources, including neurosurgeon Charles Harrison Frazier (1870-1936). Returning casualties with peripheral nerve injuries were treated in 12 peripheral nerve centers, usually located in general hospitals, where medical officers with experience in neurosurgery as well as consultant neurologists were working. Frazier provided the anatomic location of almost 2,400 peripheral nerve injuries. Byron Stookey (1887-1966) served with the British Royal Army Medical Corps (1915-1916) and the U.S. Army Medical Corps. In his Surgical and Mechanical Treatment of Peripheral Nerves (1922), he published relative frequencies of peripheral nerve injuries of 1,210 war casualties.

Of all nerve injuries described in the four countries (more than 10,000 in the various publications), radial nerve lesions were generally the most frequent. Partial lesions of the radial nerve were rare, in contrast to the frequency of partial injuries of the ulnar and median nerves. At least two eponyms are remembered from this dark period in the history of neurology. Working on different sides of the front, a French (Tinel) and a German (Paul Hoffmann:1884-1962) neurologist are remembered in one eponym, notably the Tinel-Hoffmann sign. It indicates radiating tingling sensations in the otherwise anesthetic skin area innervated by an injured nerve, upon light percussion of the area. The sign was considered to indicate the presence of new sensitive regenerating nerve fibers. Another French neurologist, Jules Froment (1878-1946), once a co-worker of Joseph Babinski, is remembered by his “signe de journal,” based on the fact that in ulnar nerve neuropathy, the action of the paralyzed adductor pollicis muscle is compensated for by the flexor pollicis longus muscle, innervated by the median nerve, resulting in flexion of the distal phalanx of the thumb.

Further reading

- Koehler PJ. Lessons from peripheral nerve injuries; causalgia in particular. In: Fine E (ed). History course syllabus. Lessons from war. AmericanAcademy of Neurology, San Diego, 2013.

- Koehler PJ, Lanska DJ. Mitchell’s influence on European studies of peripheral nerve injuries during WorldWarI. J Hist Neurosci 2004;13:326-35