Scenic Santiago, Chile, is host city for the Congress

By Renato Verdugo, MD

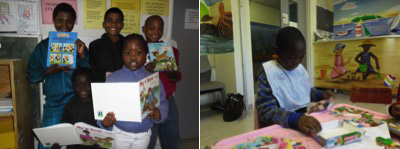

We are certain that the World Congress of Neurology will produce an impact. Chile and many countries in South America are at the edge of development. We are leaving behind health problems typical of underdevelopment although now we are facing the diseases related to aging. We are currently developing genetics, neuroradiology, rehabilitation and other techniques with the result being an in increase in the number of young neurologists and an expansion in their geographical distribution. Therefore, this is the right time to host the World Congress of Neurology in Chile, which will produce an impact within the country and in the entire Latin American region. It will not be just another congress, but it will really contribute to changing neurology worldwide, as the slogan of the Congress states.

We are certain that the World Congress of Neurology will produce an impact. Chile and many countries in South America are at the edge of development. We are leaving behind health problems typical of underdevelopment although now we are facing the diseases related to aging. We are currently developing genetics, neuroradiology, rehabilitation and other techniques with the result being an in increase in the number of young neurologists and an expansion in their geographical distribution. Therefore, this is the right time to host the World Congress of Neurology in Chile, which will produce an impact within the country and in the entire Latin American region. It will not be just another congress, but it will really contribute to changing neurology worldwide, as the slogan of the Congress states.

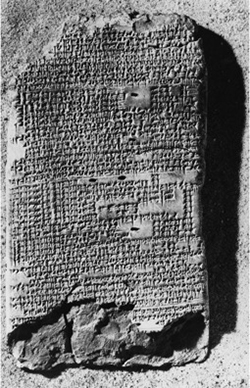

As usual, the World Congress of Neurology will include the most recent advances in neurological sciences, with the participation of renowned neurologists from around the world. It will also include different social activities to enjoy the traditions of the host country, including its famous wine. It will be an opportunity to get to know an attractive country with a varied geography, which is also easy to reach. Santiago is in the Maipo Valley, with the Andes towards the east and the Pacific Ocean on the west, each just about an hour away. It is a city that embeds the essence of the country’s history with several interesting art, historical and cultural museums, full of restaurants and different neighborhoods with different styles according to the historical period in which they developed.

Santiago is one of the safest cities in Latin America and the main cultural and economic center of the country.

Close by is the port of Valparaiso, a UNESCO world heritage city with its narrow streets climbing up the hills of the coast where one of Pablo Neruda’s houses, “La Sebastiana,” is located. Adjacent to Valparaiso is Viña del Mar, a modern and dynamic touristic city. Flying just an hour north from Santiago you will find the driest desert in the world, and flying one hour south and you will reach a dense rain forest.

The country has developed a safe democratic environment and enjoys one of the most growing economies in the region. Chile is without a doubt one of the most interesting countries in Latin America. Come to the World Congress of Neurology. We will be pleased to show you around.

A neurology fellowship is offered by the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Neurology Department at Yale University (position can be filled at either location) through the NeuroHIV Cure Consortium, which operates numerous neurological research studies in acute HIV infection and cure strategies in Thailand and Africa. The Consortium is a research collaboration directed by Victor Valcour, MD, PhD (UCSF), Serena Spudich, MD (Yale University), and Jintanat Ananworanich, MD, PhD (U.S. Military HIV Research Program).

A neurology fellowship is offered by the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Neurology Department at Yale University (position can be filled at either location) through the NeuroHIV Cure Consortium, which operates numerous neurological research studies in acute HIV infection and cure strategies in Thailand and Africa. The Consortium is a research collaboration directed by Victor Valcour, MD, PhD (UCSF), Serena Spudich, MD (Yale University), and Jintanat Ananworanich, MD, PhD (U.S. Military HIV Research Program).