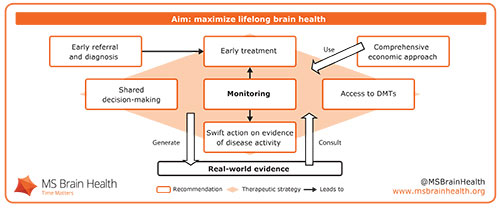

Figure 1. We recommend a therapeutic strategy based on regular monitoring that aims to maximize lifelong brain health while generating robust real-world evidence.

By Gavin Giovannoni, MD, on behalf of the MS Brain Health Steering Committee.

The goal of treating patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) should be to maximize lifelong brain health. This is the central theme of a new international consensus report from a multidisciplinary author group. Brain Health: Time Matters in Multiple Sclerosis calls for greater urgency at every stage of diagnosing, treating and managing MS. Its recommendations aim to facilitate a therapeutic strategy that minimizes disease activity (Figure 1), involving:

- Shared decision-making

- Early intervention

- Improved treatment access

- Proactive monitoring

The report was launched during a symposium, “Is the MS Community Ready to Promote Brain Health?” on the eve of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis Congress Oct. 6, 2015.

Professor Tim Vollmer outlined the brain health perspective on MS, presenting recent data underpinning its scientific basis. People with relapsing–remitting MS can lose brain volume up to seven times faster on average than age-matched controls, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of clinical trials.1 Up to a point, this damage can be compensated for by neurological reserve — the brain’s finite capacity to reroute signals or adapt undamaged areas to take on new functions.2,3 Preserving neurological reserve protects against cognitive decline4 and physical disability progression5 in people with MS. Once neurological reserve is exhausted, however, the long-term progressive phase of the disease will be unmasked, Vollmer argued. Adopting a therapeutic strategy that preserves neurological reserve by minimizing disease activity therefore should be of primary concern when people with MS and their clinicians make treatment decisions.

Professor Tim Vollmer outlined the brain health perspective on MS, presenting recent data underpinning its scientific basis. People with relapsing–remitting MS can lose brain volume up to seven times faster on average than age-matched controls, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of clinical trials.1 Up to a point, this damage can be compensated for by neurological reserve — the brain’s finite capacity to reroute signals or adapt undamaged areas to take on new functions.2,3 Preserving neurological reserve protects against cognitive decline4 and physical disability progression5 in people with MS. Once neurological reserve is exhausted, however, the long-term progressive phase of the disease will be unmasked, Vollmer argued. Adopting a therapeutic strategy that preserves neurological reserve by minimizing disease activity therefore should be of primary concern when people with MS and their clinicians make treatment decisions.

Shared decision-making relies on education. People with MS need to understand the potential long-term effects of the disease as early as possible after diagnosis, stressed George Pepper. As co-founder of the patient forum Shift.ms, Pepper stated that engaging people with MS in their own health care could be “the blockbuster drug of the 21st century.”6 He concluded by encouraging health care professionals to help people with MS to take active roles in treatment decisions and disease management, starting at the time of diagnosis.

Early intervention is vital, in order to preserve cognitive function. This was emphasized in a joint presentation by Dr. Gisela Kobelt and Professor Helmut Butzkueven, who examined MS from economic and real-world perspectives. Dr Kobelt presented some of her own economic data demonstrating that the greatest effects of the disease on employment occur at relatively low levels of physical disability.7 Professor Butzkueven concurred, and referred to results from a recent study showing that people with cognitive impairment at diagnosis were three times more likely to reach a Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale score of 4.0 and twice as likely to develop secondary progressive MS 10 years after diagnosis.8 This underscores the importance of the report’s recommendation of aiming to alter the disease course through lifestyle measures and early treatment with a disease-modifying therapy.

Improved treatment access will ultimately come from demonstrations of cost-effectiveness. Assessing the difference that treatment makes to long-term health and economic burden is of vital importance in a chronic progressive disease. To date, however, long-term economic evaluations largely have been based on models owing to a lack of data, explained Dr. Kobelt.

By monitoring disease activity and recording data in registries, health care professionals can generate robust real-world evidence that can be used to inform individual treatment decisions. Butzkueven demonstrated the power of registry data to compare the effectiveness of different disease-modifying therapies in propensity-matched people with MS.9 The overall conclusion was that the biggest change in long-term health and economic outcomes could come from targeted intervention to maximize lifelong brain health — and that real-world registry data should be generated and used to test whether this is the case. (See Figure 1)

Summing up, Symposium Chair Giovannoni stated: “I’d like every clinician, every health care professional, to think that someone with MS is giving us their brain to protect. It’s our responsibility to make sure that they get to old age with a healthy brain, so that they can withstand the ravages of aging. As a treatment philosophy, it’s as simple as that.”

Health care professionals who believe in this treatment philosophy are invited to pledge their commitment to embrace the recommendations of the report. Download the full report.

References

- Vollmer T et al. J Neurol Sci, 357 (2015):8-18.

- Rocca MA et al. Neuroimage, 18 (2003):847-55.

- Rocca MA, Filippi M. J Neuroimagin;17 Suppl 1 (2007):s36–41.

- Sumowski JF et al. Neurolog, 80 (2013):2186-93.

- Schwartz CE et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 94 (2013):1971-81.

- Rieckmann P et al. Mult Scler Relat Disor, 4 (2015):202-18.

- Kobelt G et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr, 77 (2006):918-26.

- Moccia M et al. Mult Scler (2015): doi:10.1177/1352458515599075.

- Spelman T et al. Ann Clin Transl Neuro, 2 (2015):373-87.

Acknowledgement

Independent writing and editing assistance for the preparation of this article was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, funded by grants from AbbVie and Genzyme and by educational grants from Biogen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis, all of whom had no influence on the content.

The national neurology societies of Bulgaria, China, Germany, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Mexico, Pakistan, Rumania, Saudi Arabian, Slovenia, the United States and Vietnam have honored me by nominating me for the trustee position.

The national neurology societies of Bulgaria, China, Germany, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Mexico, Pakistan, Rumania, Saudi Arabian, Slovenia, the United States and Vietnam have honored me by nominating me for the trustee position.

Neuroimaging is an important adjunct to clinical neurology. We cannot easily examine the brain directly. The neurologic exam is designed to allow us to make reasonable inferences about abnormalities of neurologic functioning, and neuroimaging helps us visualize the brain. This significantly enhances our ability as clinicians to diagnose the cause of a neurological abnormality and monitor response to an intervention. This is particularly true in neurodegenerative diseases, where the neurologic exam has been immensely assisted by neuroimaging. Indeed, with advances in neuroscientific knowledge, novel imaging techniques have been developed to provide additional insights into neurological functioning in health and disease.

Neuroimaging is an important adjunct to clinical neurology. We cannot easily examine the brain directly. The neurologic exam is designed to allow us to make reasonable inferences about abnormalities of neurologic functioning, and neuroimaging helps us visualize the brain. This significantly enhances our ability as clinicians to diagnose the cause of a neurological abnormality and monitor response to an intervention. This is particularly true in neurodegenerative diseases, where the neurologic exam has been immensely assisted by neuroimaging. Indeed, with advances in neuroscientific knowledge, novel imaging techniques have been developed to provide additional insights into neurological functioning in health and disease.