Professor Jun Kimura, MD, gives one of his legendary EMG workshops to the meeting of the Lebanese Society of Neurology on Oct 21, 2016, in Beirut.

The Official Newsletter of the World Federation of Neurology

Professor Jun Kimura, MD, gives one of his legendary EMG workshops to the meeting of the Lebanese Society of Neurology on Oct 21, 2016, in Beirut.

Yuri Takeuchi, MD

By Yuri Takeuchi, MD

A mentor is a preceptor who imparts wisdom and shares knowledge with less experienced colleagues. During medical training, it is customary to have a teacher who guides the future physician in approaching patients with the right clinical tools, bedside manner, and generosity that characterizes a good physician.

In the first chapters of his autobiographical book, Mentored by a Madman: The William Burroughs Experiment, Professor Andrew J. Lees, MD, a neurologist known worldwide for his contributions to the understanding and treatment of Parkinson´s disease and other movement disorders, describes his early beginnings as a brilliant medical student at London’s Hospital Medical College in Whitechapel. The memories of those first years in medical school will be shared by all of those who have had the illusion of becoming a physician. Regardless of the person who serves as role model for young medical students, it was evident to young Lees that the doctor-patient relationship is always unbalanced, given that the God-like physician always knows what is best for the “unschooled” patient.

As a sixth-grade child, the future Dr. Lees was introduced to the work of Richard Spruce, an American biologist who may be considered the father of modern ethnobotany. They shared a “passion for grasses and trees” and Spruce’s descriptions “left me with an indelible impression of the convulsive beauty of the forest … he also hinted in this logbooks that the plants of the rainforest held most of the secrets to understanding and manipulating the chemical systems of the human brain.”

As a sixth-grade child, the future Dr. Lees was introduced to the work of Richard Spruce, an American biologist who may be considered the father of modern ethnobotany. They shared a “passion for grasses and trees” and Spruce’s descriptions “left me with an indelible impression of the convulsive beauty of the forest … he also hinted in this logbooks that the plants of the rainforest held most of the secrets to understanding and manipulating the chemical systems of the human brain.”

Dr. Lees tells us about Spruce’s narrative of his experience during the “Feast of Gifts” of the native tribes, a ceremonial event that included the ritual drinking of the “caapi” brew. Spruce collected some fresh specimens of the liana Banisteriopisis caapi, the source of yagé, that were sent to the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew for classification and analysis in 1853.

In 1952, William Burroughs read about yagé, also known as ayahuasca, “the vine of the soul,” used by the natives for its prophetic and clairvoyance properties. In 1953, in Bogotá, Colombia, Burroughs met the charismatic Dr. Richard Schultes. Schultes introduced Burroughs to the yagé ceremonies. Dr. Lees describes that Burroughs “had glimpsed a supernatural state of being that provided him with a gateway into a proximate closed-off past.” He began a series of scientific investigations and published in the British Journal of Addiction a paper informing that the mixture of Banisteriopsis caapi with the leaves of Psychotria viridis or chacrona is responsible for the psychedelic effect of yagé.

As a confession in the book, Dr. Lees tells us of his experiences with L-Dopa and selegiline, two medications used in the treatment of Parkinson´s disease and, at his mid-60s, his journey to the Colombian Amazon forest to meet the native Indians and to experience the visions induced by the yagé ceremonies. The vivid descriptions of those self-experimental experiences by “a man of many quests,” as described by Raymond Tallis in the recent review of the book in Brain, are the most personal and intimate part of this autobiographical book.

Ethnopharmacology’s aim, as described by its international society, is the discovery of a wealth of useful therapeutic agents in the plant and animal kingdoms; the empirical knowledge of these medicinal substances, and of their toxic potential passed on by oral tradition, sometimes recorded. Many valuable drugs (e.g., morphine, taxols, physostigmine, quinidine, emetine) were found as prototypes in the attempts to develop more effective and less toxic medicines.

Dr. Lees’ message is to open our minds and show respect for nontraditional medicines and, with a strong scientific basis, to listen to our patients because those who suffer the terrible burden of neurological diseases have a sixth sense. We, as understanding physicians, should pay more attention to the voice of rainforest medicine. Perhaps, if we drink “the vine of the soul,” we might find promising alternative medicines to relieve the suffering of our fellow human beings.

By Christopher Gardner-Thorpe, MD

It would be trite to say that at no time have good international relations been more necessary than now. We live largely in communities, and, ultimately, everything we do is dependent upon the consent of others. We can achieve our human aims peacefully or by the alternative approach. Hence relations between all of us as individuals, as communities, and as nations, need to be nurtured — and this involves compromise.

Neurology affects all persons too, because we are all at risk of neurological disorders, and the specialty affects us professionally as well in our everyday jobs. Good relations between professionals are essential, as are relationships between professionals and their patients.

The neurological community worldwide is well served by local groups and societies in each country and further afield. For example, the formation of the European Academy of Neurology by the coming together of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the European Neurological Society demonstrates how on one continent, Europe, like-minded persons can come together to exchange ideas and promote good practice and good research. Communication between individuals is vital in professional life (as it is in personal life), whether face-to-face or by means of messages on paper or increasingly by electronic means. How can we facilitate the interactions between all of us who desire increased cooperation and friendship too?

International relations are enhanced by the work of organizations, including the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) with its network of contacts throughout the globe and its conferences. The publication of World Neurology offers a site for the sharing not only of information but of ideas too. The WFN is not an overtly political organization and does not engage to any significant extent in polemics. The organization made great strides during each presidency and perhaps especially during that of the late Lord John Walton, MD, who made many radical contributions to much of neurology and its science. The memorial service for Dr. Walton in early November brought many messages of support for the promotion of international relations.

Many others have promoted good international relations extending over the 20th century. The International Society for the History of the Neurosciences and the International Society for the History of Medicine, whose new president is Carlos Viesca, MD, of Mexico City, bring to communication a slightly different focus than the strictly scientific study of neurology. There is no real doubt that to study the history of our subject is to increase understanding of where we have come from and more important, why, and to help us understand how to advance further. It is not only instructive in this manner but also a good academic discipline, and enjoyable in the process — the three principles of the study of medical history. We might ask, to what extent can we learn from each other’s heritage? Surely a great deal. Failed eponymists, those whose names should have been given to the first discovery or description of something, abound. An example is the description of Duchenne muscular dystrophy to which perhaps prior description should be attributed to Edward Meryon, buried in Brompton Cemetery in London. The Dax/Broca puzzle, the Bell/Magendie controversy, and the Darwin/Wallace debate are all examples of who should have prior acknowledgement; many others examples stretch across the world. Inappropriate arguments about this and that can either sour international relations or lead to harmonious resolution, a sort of dialectic where thesis is followed by antithesis and then by synthesis. We should make the most of these opportunities to debate and inform each other.

What part do physicians play in the promotion of national and international peace? A great deal is possible — the Nuremberg Code, and discussions about physicians’ part in capital punishment and in war are examples. Recent strike action by physicians in the United Kingdom has been unprecedented, never before seen, and followed by the understanding that similar follow-up action would lead to more harm to patients, and, of course, to the profession, and the policy abandoned. The government also needs to learn that compromise is important and not to exploit a near-monopoly position within a government-controlled service for ill-founded statistical reasons, despite the many advantages that such a service holds for the population, since each of us is at one time either sick, potentially sick, and always in need of proper health care.

The planned exodus of the United Kingdom from the European Union (but not from Europe since that is a geographical matter) will change many aspects of health care. On the one hand, there will be greater frfeedom to control the ways in which governments act. On the other hand, the controls that come from being part of a larger community (the European Union) will be relinquished. The law of unintended consequences will have free reign with lots of heart-searching afterward.

There are many facets to our need to promulgate relations between nations and the manner in which we can promote these bonds. Within medicine, we see many possibilities for shaping the health and happiness of human beings, and shifting forces should make us wary and constantly vigilant to new opportunities. Our Strengths and Weaknesses bring Opportunities and Threats – the SWOT analysis. As medics and others who take part in health care, we must make the most of our strengths and opportunities by fostering our international relations, since these are precious and could so easily be lost by inaction, as well as by inappropriate actions.

Edward J. Fine, MD

By Edward J. Fine, MD

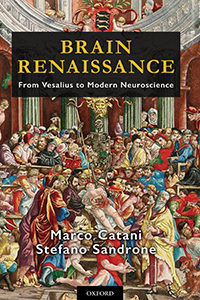

In Brain Renaissance From Vesalius to Modern Neuroscience, authors Marco Catani and Stefano Sandrone have written chapters based on translations from Andreas Vesalius’ book on the brain from his De Humani Corporis Fabrica, followed by commentaries. The book is published by Notting Hill Editions, 2016.

The first chapter adroitly reviews the history of dissection of human bodies and Galen’s hegemony prior to Andreas Vesalius’ first edition of his seminal and revolutionary anatomical textbook of 1543.

Chapter 2 recounts Andreas Vesalius’ illustrious lineage in a family of physicians and pharmacists who attended royalty. Andreas Vesalius was born on Dec. 31, 1514, in Sablon, a neighborhood of Brussels. His father was the royal apothecary (pharmacist) to Charles V of Spain. At age 15, Vesalius entered the Castle College in Leuven, which promoted the philosophy of humanism. At age 18, Vesalius left Leuven to study medicine in Paris.

Chapter 3 recalls Vesalius’ medical education in Paris and his encounter with profound differences between what he saw in human cadavers and Galen’s incorrect descriptions. Galen’s texts of anatomy were the canon from the time of the Roman Empire to publication of Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica. Vesalius left Paris abruptly without graduating, due to war between Henry II of France and Charles V of Spain, patron of Vesalius’ father.

The fourth and fifth chapters highlight Vesalius graduating from Leuven Medical School, traveling to and joining the medical school at Padua, Italy, renowned for its eminence in teaching anatomy from human dissection. Through dissection, Vesalius found so many more errors in Galen’s descriptions of human anatomy that Vesalius concluded Galen had dissected monkeys and other animals rather than humans. Chapters 6, 7, and 8 deal with production of the Fabrica, a volume of nearly 700 pages of which the seventh book deals with the brain, making 200 woodcuts used to print illustrations, and sources for backgrounds in anatomical illustrations. Vesalius’ friendship with Contarini, the podesta (chief magistrate) of Padua, provided corpses of recently freshly executed criminals for dissection.

Disgusted by nefarious intrigues of jealous surgeons and physicians at the Court of Phillip II in Spain, Vesalius escaped to the Holy Land after contacting colleagues who would petition his return to the chair of anatomy and surgery at Padua. The authors cite reliable accounts that Vesalius studied medicinal herbs there. He died attempting to return to Padua. His death on the island of Zante was attributed to exhaustion from scurvy, or illness caused by a prolonged voyage in the tempestuous Mediterranean Sea.

Chapter 13 defines Vesalius’ concept of the brain as the source or sensation and voluntary movement. Vesalius was versed in comparative anatomy: “… there is no difference at all in the structure of the brain in the parts that I have dissected in the sheep, goat, monkey … when compared with the human brain.” He recognized that man’s intelligence was due to “… the human brain larger proportionally to his body but also larger than all of the animals … .” Vesalius stridently denied the presence of the rete mirabilie in the base of the human skull, a structure Galen insisted was present in humans. This structure is part of bovine skulls. Vesalius also decried Galenic beliefs about ventricular function.

In Chapters 14 and 15, Vesalius denotes dura and pia as hard and soft membranes surrounding the brain. He reminds readers of similarities and differences between these structures and pericardium and epicardium. Vesalius presciently mentions that the surface of the thin membrane (pia) is covered with aqueous liquid (cerebrospinal fluid) and that this membrane “provides a defensive wall for the brain against collisions with the skull.”

In Chapter 16, Vesalius describes the corpus callosum, brainstem, and cerebellum with emphasis on the position and external surface of the cerebellum. Vesalius rebuked Galen for not describing accurately the morphology of the cerebellum: “Oh, Galen, you have been deluded without good reason by things of little importance and sometimes also by your apes.” Vesalius comments on the mid-position of the corpus callosum — that it is a band of fibers connecting the hemispheres. The commentary begins with the statement that Galen and Vesalius assigned a mechanical function to the corpus callosum to keep the cortex from collapsing into the ventricles.

In the commentary, we learn that some anatomists succeeding Vesalius assigned absurd roles to the corpus callosum such as the seat of the soul. Spurzheim and Gall proposed that the corpus callosum “contributed to producing action and reciprocal reaction between the hemispheres.” We read that persons born with agenesis of the corpus callosum may be nearly normal or be developmentally impaired. Catani and Stefano Sandrone accurately summarized Gazzaniga and Sperry’s research on the functions of persons who underwent transection of the corpus callosum for control of epilepsy. Catani and Sandroni inform us that the anatomical fornix was linked to arches in Rome where prostitutes met their customers. They recounted the discovery of connections of the fornix to mammillary bodies by Felix Vicq d’Azyr in 1786. These authors advanced the idea that Papez, who is credited for “discovering” a circuit for emotion in 1937, was actually scooped by Paul Broca in 1878. Moreover, Christfried Jakob’s circuit for emotions closely resembled James Papez’s 1937 diagram. John Fulton and Jacobsen observed chimps were less aggressive after they had resected portions of their frontal lobes. Antonio Moniz, assisted by the neurosurgeon Almeida Lima, injected pure ethanol into frontal lobes of chronic schizophrenics. They were convinced they had improved the patients’ behavior. They were visited by Walter Freeman, an ambitious neurologist, who later performed 3,000 trans-orbital leucotomies that partially controplled violent behavior, but caused profound inability to plan and initiate activities. Catani and Sandrone summarized the tragic case of H.M. who suffered anterograde amnesia after bilateral removal of his hippocampi in an attempt to control partial complex epilepsy.

In the chapter on the pineal gland, Vesalius localizes this structure to the base of the third ventricle and its function as a gland. Sandrone and Catani summarized knowledge of pineal function from Descartes’ opinion as the seat of the soul to current knowledge of its role in secretion of melatonin. Connections between the photoreceptors in the eye to the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus and then to the pineal gland control increase melatonin release from the pineal gland at night and suppress its secretion during daylight. I was amused to learn that farmers expose hens to excessive artificial light to suppress melatonin release and increase egg production.

Although the titles of chapters on Testes and Buttocks of the Brain and Sex on the Hills may strike readers as risqué, the content is about the colliculi and the dependent pineal gland resembling these organs. Catani and Sandrone explain lucidly how the expansion of occipital lobes replaced the superior colliculi as the principal structure for vision in the ascent of evolution from birds to man. They mention the role of the inferior colliculus in the auditory pathway from medulla to the primary auditory cortex.

In Chapter 22 on the cerebellar processes, Vesalius lambasted Galen for his fanciful and fallacious concept of the function of the cerebellum as a valve to control the flow of the animal spirits to the spinal cord and then to the nerves. Vesalius vehemently objected to the misnomers of Galen used to describe folds of the cerebellar cortex as vincula or chains.

Commentary following Vesalius on the cerebellum contains a plethora of interesting facts, including that the elephant has the largest cerebellum in absolute and relative size. We learn that Costanzo Varoli removed the brain from the skull, inverted it, and described the pons (Latin for bridge). Thomas Willis in 1664 discovered its three peduncles. Albrecht von Haller corrected Willis’ statement that the cerebellum controlled involuntary movements of the heart and lungs by locating these functions in the brainstem. Luigi Rolando used electrodes supplied with current from Volta’s electrical pile to stimulate regions of the brains of pigs. He found muscular movements were strongest when he stimulated the cerebellum. Pierre Flourens in 1824 correctly assigned coordination of movement to the cerebellum and movement to the spinal cord. Catani and Sandrone end their commentary tersely, describing cerebellar cellular anatomy and Golgi’s vicious defense of the syncytial theory of brain architecture in his Nobel lecture in 1906.

Vesalius described the infundibulum as the structure that collects and drains cerebral phlegm. He believed drainage from the infundibulum out of the cranium occurred through spaces surrounding arteries, veins, and nerves. The commentary describes the connections between the hypothalamus and pituitary, and the regulatory effects of the hypothalamus on thyroid, adrenal, and ovarian or testicular hormones. The authors cited the amazing case of the pituitary giantess Aama Bataillard, whose autopsy revealed a greatly enlarged pituitary. They summarized extensive research on the influence of pituitary extracts on growth and maturation in Chapter 24.

Subsequent chapters deal with the variations of the blood vessels of the brain and Vesalius’ precise description of structures within the eye. Vesalius’ closing chapter deals with methods on how to remove and dissect the brain.

Chapter 31 contains useful chronological tables of advances in microscopy, electrophysiology neuroanatomy, and neuroimaging. A subsequent chapter tersely comments on phrenology, discovery of animal electricity, and the action potential.

The following chapters provided more information on advances made in staining brain tissue by Golgi and Cajal, emergence of the neuronal doctrine, and Cajal’s declaration of proof of dynamic polarization based on Cajal’s microscopic observations. Staining techniques that differentiated regions of human brain led to construction of elaborate maps by Campbell and Brodman.

Chapter 37 omits the discoveries of Richard Caton who first recorded electrical potentials recorded from cerebral cortices of moving mammals (electrocorticography) in response to light and tactile stimuli. No comments are offered regarding Hans Berger’s meticulous descriptions of normal and abnormal EEG activity in awake and sleep, after trauma, and during seizures. The authors’ final chapter summarizes the emerging science of functional MRI imaging of connections between regions of brain during specific tasks.

This book has some minor but detracting errors and omissions. The authors did not mention the Papal edict that blocked human dissection for four centuries and how the Medici family’s Pope ended this prohibition. This information would explain the resurgence of human cadaver dissection in the Renaissance. In the section about limbic system connections to the prefrontal cortex, these authors should have mentioned that Ignaz Moniz received the Nobel Prize for discovery of the harmful prefrontal leucotomy, but not for initiating the highly beneficial technique of cerebral angiography. In some areas, the commentary seems haphazard and sometimes omits important material.

These authors’ commentary on the cerebellum omits anatomical studies of James S. Risien Russell, who discovered the uncinate fasciculus, known as the hook bundle of Russell. That chapter overlooks clinical observations of American authors Charles K. Mills and Theodore Weisenberg regarding lesions in the anterior versus posterior vermis that cause loss of tone and respectively falling forward or backward. No mention was made of Babinski’s discovery of dysdiadochokinesis in 1902 or Granger Stewart and Gordon Holmes’ publication in Brain in 1904 on loss of check or “rebound” in patients with cerebellar hemispheric lesions. This chapter minimizes Gordon Holmes’ meticulous and exhaustive observations of 40 World War I soldiers as they recovered from gunshot wounds to their cerebella. Holmes described initial hypotonia of limbs ipsilateral to destruction of the cerebellar hemisphere, later deviation of gait toward the side of the cerebellar hemisphere. The figure showing extreme hypotonia of a soldier is the sole illustration from Holmes’ opus. The authors could have included Holmes’ graphic recordings of disturbed movements induced by cerebellar hemispheric lesions.

The commentary would be improved by comment on the Galvani versus Volta controversy, the landmark publication of The Functions of the Brain by David Ferrier in 1876, based on ablation and electrical stimulation of cerebral cortex of primates and other mammals. Elaborating on discoveries of Caton and Berger, cited only in the chronological tables, would have added much.

Typographical errors mildly mar the book. In pages 40 and 41, the erroneous date 1664 appears three times instead of 1564, which is the correct year of Vesalius’s trip to the Holy Land and his death. Footnote 27 contains a typographical error, “chartoid,” for carotid. Nonetheless, these minor defects do not blemish a book that contains a vibrant translation of Vesalius’ Book Seven and plethora of information in their commentary.

Despite these omissions, this is the book to own for those who are not Latin scholars but desire to read an accurate translation of the writings of Vesalius. Much of the commentary upon anatomical, clinical, and pathological discoveries made after Vesalius is germane and informative for understanding the development of neuroscience. Oxford Press substantially bound this hardcover book, printed an attractive cover, and precisely reproduced figures in the appendix from Vesalius’ Book Seven. I can attest to the clarity of these illustrations, having viewed both original editions of the Fabrica on visiting the medical library at Leuven. MRI, photographs, and illustrations from neurological and neuroanatomical literature were intelligently selected and faithfully reproduced. A revised edition following some of these suggestions would be well received.

By Wolfgang Grisold, MD

By Wolfgang Grisold, MD

The book Teaching and Tuition of Neurology and Neurosurgery in Indonesia During One Century (1850-1950) by Antoine Keyser provides a history of neurology in Indonesia, covering development of this field in different epochs of science and the changing political situation. It also memorably describes the research, theories, and final detection of beriberi in this part of the world.

Indonesia is a large country, and looking at its population of 240 million, distributed on 3,000 islands, it is surprising that we know so little about the country and its neurology. The territory of what now is Indonesia is briefly followed through history, which is important in order to understand the influence of different medical schools, mostly from the Dutch academic background, on the development of the health system, including neurology. The book describes the emerging specialty of neurology in close context to psychiatry and the later emerging field of neurosurgery.

The reader will find many familiar names from European neurology involved in research and development. The book also includes a short sketch on specialization in psychiatry in Indonesia. In particular, the studies of the Swiss psychiatrist Emil Kraeplin (1856-1926) visiting and studying the cultural factors influencing mental diseases is a good example.

The author chronologically looked at publications and topics of interest to neurologists. The most impressive story is that of beriberi, and a separate chapter not only teaches the importance of this disease for the region, but the tortuous path the final discovery of the cause and offering of effective treatment of this condition. This story, like the similar story of scurvy, teaches how inflexible dogma, conventions, and large organizations (where individuals including prisoners, soldiers, and patients were kept under uniform conditions) can endanger the health of persons. Also, the author’s description of vitamin B1 deficiency and its effect on the health of people is a worthwhile lecture for teaching purposes.

This book mirrors the field of neurology in the past 100 years worldwide, using the example of Indonesia. The development of local conditions are described, based on historic facts as well as publications.

It is a good example of how a book comprising narrative and facts can provide valuable background on neurology in an individual area. The World Federation of Neurology could be well advised to encourage its members to produce similar outlines of the history and development of neurology in its regions.

Federico Pelli-Noble, MD, PhD

By Federico Pelli-Noble, MD, PhD

Dr. Pedro Nofal speaks to the community about dementia in San Miguel de Tucuman, Argentina.

World Brain Day was celebrated on July 22, 2016, in Tucuman, Argentina. All of the Organizations of Health were present, and the topics included dementia, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, and neuromuscular diseases. Nearly 200 people attended the conferences. It was a nice journey and a successful event, alerting the public about the increasing neurological problems related to an aging population.

Community members and physicians take part in World Brain Day in San Miguel de Tucuman, Argentina. Alejandro Helguera (from left), Maria Ester Totongi, and Drs. Federico Pelli-Noble, Andrea Arcos, Pedro Nofal, Oscar Iguzquiza, and Alejandra Molteni.

John D. England, MD

By John D. England, MD

August 2016 was an awful month for the world of neurology and the Journal of the Neurological Sciences. We suffered the loss of two outstanding academic neurologists, Omar Khan, MD, and Donald Gilden, MD. Both were valuable members of the Editorial Board of the Journal of the Neurological Sciences, and both were outstanding neurologists and academic teachers and researchers. Their loss creates a great void in the world of neurology.

Dr. Khan, professor and chair of the department of neurology at Wayne State University, passed away Aug. 13 at age 53. He had been a faculty member at Wayne State since 1998 and chair of the department of neurology since 2012. He was an internationally known expert in multiple sclerosis and served as the director of the Wayne State University Multiple Sclerosis Center and Magnetic Resonance Image Analysis Laboratory. He served as principal investigator of more than 55 clinical trials and published extensively in the field of multiple sclerosis. He was extraordinarily helpful as a reviewer and Editorial Board member of the Journal of the Neurological Sciences.

Dr. Gilden, professor and former chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, passed away Aug. 22 at age 78. He was the department’s longest-serving chair (1985-2009) and led the department into an era of prominence. He exemplified the fast-disappearing triple threat academic with his outstanding abilities in clinical neurology, education, and basic research. He was internationally renowned as a foremost expert in the biology and pathogenesis of varicella zoster virus (VZV). He was the first to demonstrate that VZV DNA can be found in normal human sensory ganglia neurons, and described VZV-vasculopathy of brain. His most recent studies concentrated upon the association of VZV with giant cell (temporal) arteritis. He authored or co-authored 420 papers, many of which are now seminal articles in the field of neuro-virology and neurology. On a personal note, I owe him a great debt of gratitude since he offered me my first academic faculty position and helped guide my academic career. He was a tireless and gifted reviewer and contributor to the Journal of the Neurological Sciences.

Dr. Gilden, professor and former chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, passed away Aug. 22 at age 78. He was the department’s longest-serving chair (1985-2009) and led the department into an era of prominence. He exemplified the fast-disappearing triple threat academic with his outstanding abilities in clinical neurology, education, and basic research. He was internationally renowned as a foremost expert in the biology and pathogenesis of varicella zoster virus (VZV). He was the first to demonstrate that VZV DNA can be found in normal human sensory ganglia neurons, and described VZV-vasculopathy of brain. His most recent studies concentrated upon the association of VZV with giant cell (temporal) arteritis. He authored or co-authored 420 papers, many of which are now seminal articles in the field of neuro-virology and neurology. On a personal note, I owe him a great debt of gratitude since he offered me my first academic faculty position and helped guide my academic career. He was a tireless and gifted reviewer and contributor to the Journal of the Neurological Sciences.

In our ongoing attempt to inform readers of important and interesting new developments in the journal, the editorial staff has selected two new “free-access” articles for our readership.

Mustapha El Alaoui Faris, MD

By Mustapha El Alaoui Faris, MD

The Moroccan Society of Neurology had the recent privilege of using Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology through the partnership between the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the World Federation of Neurology (WFN).

The first working session on May 4, 2016, during the National Congress of Neurology in Marrakech, Morocco, used the Continuum issue on Epilepsy. A second session was held Sept. 24, 2016, using the Dementia and Multiple Sclerosis and Other Demyelinating Disorders issues. The next session will be Dec. 17, 2016, in Rabat, Morocco, and will involve the Continuum issues on Movement Disorders and Neuroimaging.

For organizing the Continuum sessions, the Moroccan Society of Neurology has established the following rules:

Moroccan neurologists take part in the Sept. 24, 2016, Continuum session in Rabat.

Young neurologists and more senior neurologists were equally pleased to share this experience in a studious, relaxed atmosphere. Moroccan neurologists enjoyed the didactic nature of the Continuum program, the personal reflections of various authors of Continuum’s articles in their fields of interest, and the clinical case studies. They would like to thank the staffs of the AAN and the WFN for allowing the use of this excellent educational document and especially to thank Steven L. Lewis, MD, editor-in-chief of Continuum, and Helen Gallagher, WFN CME program manager, for their efforts.

I invite neurologists worldwide to enjoy the Continuum program, an excellent educational tool for continuing education in neurology, thanks to the efforts of the AAN and the WFN.

By Kate Riney, MD, PhD

Although there is much information on the internet about epilepsy and seizures, there is a glaring absence of a single source of information that aligns with the international classification and provides an organized presentation of the many seizure types and syndromes to help with diagnosis and treatment.

Although there is much information on the internet about epilepsy and seizures, there is a glaring absence of a single source of information that aligns with the international classification and provides an organized presentation of the many seizure types and syndromes to help with diagnosis and treatment.

This information gap was recognized and led to the International League Against Epilepsy’s (ILAE) epilepsydiagnosis.org project, which was launched formally in September 2014. It has been a unique resource in medicine and has harnessed the power of the internet to present the complexity of the significant amount of new information now available about the epilepsies and their etiologies, in a manner that is concise, current, and accessible to a global audience. It is as relevant to those in primary and secondary health care settings as it is to those in tertiary epileptology practices. It also shows promise as an instructional and training resource for those who are new to medicine.

The project was conceived and developed by the ILAE’s Commission on Classification and Terminology (2009-2013) and this Commission’s Diagnostic Manual Taskforce, in partnership with eResearch at the University of Melbourne, Australia. The project has been further developed by the ILAE’s Commission on Classification and Terminology (2013-2017) and this commission’s epilepsydiagnosis.org and syndromes task force.

Since the release of epilepsydiagnosis.org, its reach has steadily increased each month. Approximately 10,000 unique visitors from around the world access the site each month, viewing pages more than 40,000 times per month. Website users span professional groups that range from those in primary care to those working in tertiary health care settings. The ongoing growth in user engagement with the website continues to occur organically through relevance of the website content to those in clinical practices where epilepsy is diagnosed and managed.

Website Goals

Website Offerings

The structure of the website reflects the importance of seizure type, syndrome, and etiology in clinical practice, and how these aspects of the epilepsy interrelate. You will find:

Epilepsydiagnosis.org complements resources available through Epileptic Disorders, the ILAE’s official educational journal, for professionals with particular interest in epilepsy. However, epilepsydiagnosis.org, through its open access format, also provides an increased reach to health professionals from primary and secondary health care settings who see patients with epilepsy, and is relevant for community organizations and for the general public due to the simple and clear presentation of information.

Please visit and use epilepsydiagnosis.org. Your comments and suggestions are welcome in the Give Feedback section.

Raad Shakir, MD

By Raad Shakir, MD

The World Congress of Neurology (WCN) is the major event for a host society and is as important for the regions. There is no doubt that in each of the last four congresses the impact on the regions was positive, but to a varying degree as expected. This is one of the main reasons for holding congresses in rotation across continents.

If we start with Bangkok in 2009, the Congress was well attended and drew delegates from neighboring countries. This success resulted in the consolidation and formal establishment of the Asian Oceanian Association of Neurology (AOAN). The World Federation of Neurology (WFN) provided the AOAN with seed money to establish its legal status, produce its bylaws, and hire its own professional conference organizer. This indeed happened, and the AOAN is now a well established and financially viable association based in Singapore. This was further consolidated by their most successful subsequent Congress in Melbourne in 2012. This was made even more successful as they drew on the huge experience of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Neurology. We have to remember that Sydney hosted a successful WCN in 2005. This made the Australian neurologists experts in making congresses work. The AOAN was well organized, and the excellent Congress reinforced the status of the AOAN. Subsequent meetings in Macao and Kuala Lumpur this year continued the progress. It is clear that although the AOAN was established in 1961 with its first meeting in Tokyo, its legal status, bylaws, and financial structure only started to happen following the success of WCN Bangkok.

If we move now to WCN Marrakesh, the situation is even more spectacular. The Congress banner was “With Africa For Africa.” Prior to the WCN, the only African association was a combination of neurologists and neurosurgeons. The Pan African Association of Neurosciences (PAANS) has been in existence for nearly 40 years, but the structure and function has never been brought to the modern age. Moreover, the neurosurgeons, except a few, decided to form their own African setup and left PAANS. It was high time to organize African neurology in one solid organization with proper membership, a constitution, and bylaws as well as legal status. This aim was paramount for African neurologists who saw the Marrakesh Congress as the opportunity to establish their academy. The Moroccan society and the WFN agreed to create an Africa fund. This came from the profits of the WCN and was specifically dedicated for the establishment of an African neurology association. Although it took four years, with good will and massive organization of the head of the Africa initiative Gallo Diop, MD, PhD, of Senegal, and the WFN Regional Chair Riadh Gouider, MD, of Tunisia, it all came to fruition.

In August 2015, a meeting in Dakar of 27 African associations established the African Academy of Neurology (AFAN). The bylaws and constitution were approved, democratically elected officers were chosen, and now the organization is officially registered as a nonprofit organization in Cape Town, South Africa. The needs of Africa are massive. President Johan Aarli, MD, established the WFN Africa task force in December 2006, and we are delighted that the organization is now fully functional. The first Congress of AFAN is going to be held jointly with the Congress of the Pan Arab Union of Neurological Societies in March 2017 in Tunisia.

One might rightly think that neurology in Europe is well organized and education is advanced, which is certainly the case. However, at the time of the WCN 2013 in Vienna, there were two continental neurological organizations in deep discussions and negotiations on a merger. At the time of the WCN Vienna, one of the two regional organizations, the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) fully participated in the WCN as a partner and canceled its own Congress for that year. This resulted in consolidating the attendance for the WCN. The Austrian society worked closely with the EFNS to make the Congress a huge success. The birth of the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) followed with the merger of EFNS and the European Neurological Society. This merger started with the 2015 joint meeting in Istanbul, and the first EAN Congress was held in 2016 in Copenhagen.

Moving on to Latin America, the Santiago WCN was held in 2015. This was the second Congress in the continent following Buenos Aires in 1993, and the Chilean colleagues performed marvelously. The Congress was a success scientifically, socially, and financially. The regional association was in the process of being formed. Although neurological congresses had been held since the 1960s, they followed the same pattern as elsewhere in the world. A host country holds the Congress with the full responsibility of organization and outcome; there was no set structure and the region, although participating, did not reap the rewards of the Congress. There had been an intense discussion between Latin American neurologists over the previous four years, which culminated in a pivotal meeting during the Marrakesh Congress and proceeded to further meetings under the auspices of the WFN. These deliberations were financially supported fully by the WFN and culminated in the formation of the Pan American Federation of Neurological Societies (PAFNS). The constitution and bylaws were written, and the final step was in Santiago, when it was decided to host the PAFNS administrative office in Chile. The Chilean society agreed to offer office facilities, and the constitution and bylaws were translated into Spanish. The PAFNS is now registered as a nonprofit foundation in Chile. This will allow future developments and financial stability to disseminate neurological training in Latin America.

Again like Africa, the Santiago Congress provided financial provision for PAFNS. The WFN and Sonepsyn (Chilean Society) have given up some of their profits to facilitate the establishment of the PAFNS. This was supplemented by a grant from the American Academy of Neurology, and the three organizations are involved in providing seeding for the nascent PAFNS. It has been most heartening to see that the Mexican Academy of Neurology stepped up to host the first PAFNS Congress in October 2016 in Cancun.

All of this only demonstrates the close relationship and tight collaboration of the six WFN regional organizations in doing all they can to consolidate their status and support each other, which is the essence of regional empowerment as one of the pillars of the WFN strategy for improving neurology worldwide.

President's Column

World Brain Day

From the Editors

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement for First Vice President: Prof. Riadh Gouider

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement for First Vice President: Tissa Wijeratne

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement for WFN Elected Trustee: Chandrashekhar Meshram

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement for WFN Elected Trustee: Ghazaleh Tabatabai

Candidate Statement

Candidate Statement for WFN Elected Trustee: Mayela Rodriguez-Violante

© 2025 World Federation of Neurology. All rights reserved.