The inspiring work and legacy of JSS

By Mamta Bhushan Singh

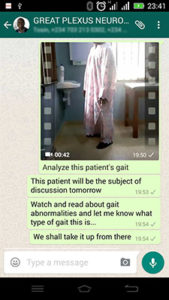

Health worker, physiotherapist, and visiting neurologist visit the home of a stroke patient to check on her progress and provide some guidance on rehabilitation.

Eight thousand neurologists descended upon Kyoto where we are attending the XXIII World Congress of Neurology, and where this article was written. If the best that humankind can be, do, and achieve has to be witnessed, Kyoto may be the correct place.

I am not making this statement lightly, but sharing my assessment of the city and its people after being here for a few days. There are very few places that inspire; Kyoto is certainly one of them.

Jan Swasthya Sahyog, or JSS, which I write about here, is also an inspirational place. Why did I think of JSS while I am in this world-class amalgamation of the ancient, traditional, and cutting-edge modern? Well, so is JSS! While JSS makes a serious attempt to make available to the local tribal Indian communities every effective modern treatment, there is an equally passionate commitment to preserve all that is good, wholesome, and healthy in the traditions, practices, and environment of the region.

JSS is in Ganiyari, Bilaspur, in the central Indian state of Chattisgarh. This is a remote, rural, neglected region, and JSS is carrying almost the entire burden of providing health care here.

Being Struck

Patients come to JSS from far, traveling for up to two days to reach there. In spite of JSS having long 12 to 14 hours of clinics, patients may have to wait up to several days for their turn. This is how they leave a bag or tie a piece of cloth to mark their place in the queue.

On the way from JSS to some of its outreach clinics is a forest called Achanakmar. For non-Hindi-speaking friends, this would roughly translate into “being struck, suddenly.” I am not sure how many people in or around the forest have been “struck” by animals from this forest. In the gentler surrounds of Ganiyari, the tribal Baigas, Gonds, Abhuj Maria, and many others are being struck with far more regularity and finality by something else. We would like to believe that what is striking them is disease; and in some ways, it is. Yet, what is striking them far more frequently and harder, I believe, is poverty. And apathy.

The local population that JSS serves is chronically malnourished. Life is hard, regular employment only available in certain seasons. Alcoholism adds another layer to the population’s challenges. The favored spirits are derived locally from the Mahua tree. Men and women are equally afflicted. Families often tend to be large with many families having five or more children.

Under such circumstances, if disease strikes, the blow can be final. Diseases are rampant. Tuberculosis and diabetes may be major problems, but anemia, infections, infestations, deficiency syndromes, sickle cell disease, bites, stings, and every other disease one can think of, jostle for attention and resources.

Health Care

The health worker exchanges pleasantries with me as I go through patients who have been specially called to the epilepsy clinic at Bahmni. Bahmni has one of the outreach clinics that JSS runs in the region.

If you look around for the available public health care for these indigenous people, you are not surprised. There is almost nothing. These people do not matter, and we are too busy and important to be bothered about them. So people continue to fall sick, suffer, and die. God forbid, they show a little spunk and try getting treatment in one of the private clinics or hospitals at the nearby Bilaspur or the slightly further Raipur. There is an extremely high likelihood of them then falling into an endless spiral of debt from which they might never recover.

Enter JSS. Each word in this name is meaningful. A few bold, committed, and extremely unusual doctors initiated the project more than a decade ago. Spend a few days at JSS and what impresses you is how rooted the idea is in the local community and how organically the community connects with it. Each one is an equal stakeholder. The founder doctors had the audacity to not only conceive such a project but have also dedicated their lives to bringing their vision to fruition. The community in its response surpasses my expectations. Every time I visit JSS, I wonder why we do not more often engage with the communities that we work in?

Miracles

JSS is not only a hospital. It is people working for themselves, facilitated by the guidance and mentoring of committed doctors. Attention is crucially being paid not only to the cure of disease but also to its prevention in the community. People are being educated and made aware of sickness and health. Treatments are being re-thought and re-designed in accordance with local needs and within the framework of available logistics. The role of the generalist, which has long lost any shine in the medical profession, is being explored, even celebrated.

What Is JSS?

The vision of Jan Swasthya Sahyog, found at http://www.jssbilaspur.org/: “To develop a low-cost and effective health program that provides both preventive and curative services in the tribal and rural areas of Bilaspur and surrounding areas of Chhattisgarh in central India. We strongly believe that access to health care should not be denied to anyone due to lack of money or due to discrimination on account of caste, sex, religion, and social class.”

Even if I tried, I do not think I could better describe what JSS does. Visit the JSS FaceBook page to see some of their projects: https://www.facebook.com/jssbilaspur/.

One often gets to see miracles of the generalist at JSS. While I am there, a 60-year-old farmer walks in with recently appeared symptoms of difficulty in using language. His brain imaging is urgently arranged from Bilaspur. The scanner looks far worse than the patient.

We discuss this patient around 4 p.m., and I am worried about where we are going to find a neurosurgeon. This seems to be a brain abscess, and surgery is needed both for confirmation of the infectious nature of the lesion as well as for treatment. There is not much time to fret over it, and I get busy with epilepsy patients. Later in the evening, I discover that the quiet, unassuming, soft-spoken person trained to be a pediatric surgeon has gone rogue and performed neurosurgery.

It is a success. I would consider this otherwise modest surgery life saving over here. I did not hear any applause anywhere or even much surprise. This is what everyone at JSS does quite regularly. They challenge themselves and break boundaries.

Over the last 10 years, I have traveled a lot and been to scores of Indian small towns and villages and met hundreds of health care professionals. Many of them come across as being very committed and caring. Yet, I have never seen a patient being brought for a consultation not by his family but by a health worker. At JSS, I was surprised to see that this happens quite regularly.

I am told that 13-year-old Birju’s parents have recently migrated to Allahabad in search of a livelihood. He and two of his siblings are staying with grandparents. The village health worker has brought Birju to the epilepsy clinic. Another young patient’s parents are erratic in getting her to the epilepsy clinic. I am informed that they are Mahua addicts and often inebriated. The village health worker who has brought her knows all the details that I need and does not seem judgmental or annoyed. I feel guilty because I am feeling both of these emotions very intensely. I have so much to learn from these villagers.

People can be very poor. They can be so poor that they are unable to afford medicines that they desperately need to remain seizure-free and that cost as little as 100 rupees per month (~USD 1.20). I met a few patients who told me that they knew that their medicines should not be missed. Yet, every once in a while, they just do not have the money to refill their prescription. My long-held dream of setting up an “Epilepsy Drug Bank” reappears. When will I be able to get this done?

The guiding light and driving force at JSS is empathy and concern for the community. Cost of care is designed thoughtfully and not set in stone. Individual patient circumstances are kept in mind while handing over bills. Patients open up and talk. They do not appear overwhelmed, as they seem to be in the tall steel and glass structures called “hospitals” in big cities. I wonder why we do not have more JSSs. This health provision model works and has profound lessons especially for doctors, health planners, and governments. Are we ready to listen yet?

The Society of Neurologists of the Republic of Moldova developed a poster to increase awareness of stroke risk factors and symptoms among the population. The country’s 300 neurologists take care of stroke patients. But measures to prevent stroke, recognize stroke symptoms and signs, and hospital admission with adequate thrombolytic treatment are still inefficient.

The Society of Neurologists of the Republic of Moldova developed a poster to increase awareness of stroke risk factors and symptoms among the population. The country’s 300 neurologists take care of stroke patients. But measures to prevent stroke, recognize stroke symptoms and signs, and hospital admission with adequate thrombolytic treatment are still inefficient.