Babylonians described epilepsy, stroke, psychoses, depression, anxiety

By Edward H. Reynolds

James Kinnier Wilson and Edward H. Reynolds.

In the last 25 years I have had the privilege of collaborating with James Kinnier Wilson (JKW) on Babylonian texts of neurological and psychiatric disorders. JKW is a Cambridge-based assyriologist and son of the distinguished neurologist, Samuel Alexander Kinnier Wilson (1878-1937) (see World Neurology, October 2014).

It was believed that studies of disorders of the nervous system began with Greco-Roman medicine, for example, epilepsy, “the sacred disease” (Hippocrates) or “melancholia,” now called depression. Our studies have now revealed remarkable Babylonian descriptions of common neuropsychiatric disorders a millennium earlier.

There were several Babylonian dynasties with their capital at Babylon on the River Euphrates. Best known is the Neo-Babylonian Dynasty (626-539 BC) associated with King Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC) and the capture of Jerusalem (586 BC). But the neuropsychiatric sources we have studied nearly all derive from the Old Babylonian Dynasty of the first half of the second millennium BC, united under King Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC).

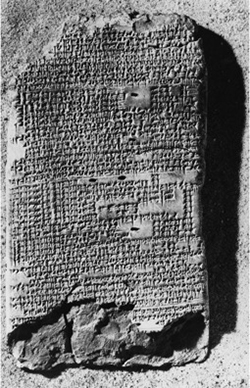

The Babylonians made important contributions to mathematics, astronomy, law and medicine conveyed in the cuneiform script, impressed into clay tablets with reeds, the earliest form of writing, which began in Mesopotamia in the late 4th millennium BC (see Figure 1, page 8). When Babylon was absorbed into the Persian Empire cuneiform writing was replaced by Aramaic and simpler alphabetic scripts and was only revived (translated) by European scholars in the 19th century AD.

A Babylonian cuneiform text on epilepsy. Obverse of BM47753 in the British Museum.

The Babylonians were remarkably acute and objective observers of medical disorders and human behavior. In texts located in museums in London, Paris, Berlin and Istanbul, we have studied surprisingly detailed accounts of what we recognize today as epilepsy (Figure 1), stroke, psychoses, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), psychopathic behavior, depression and anxiety. For example, they described most of the common seizure types we know today, e.g., tonic clonic, absence, focal motor, etc., as well as auras, post-ictal phenomena, provocative factors (such as sleep or emotion) and even a comprehensive account of schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy. Early attempts at prognosis included a recognition that numerous seizures in one day (i.e., status epilepticus) could lead to death.

The Babylonians recognized the unilateral nature of stroke involving limbs, face, speech and consciousness, and distinguished the facial weakness of stroke from the isolated facial paralysis we call Bell’s palsy. They did not, and perhaps could not, describe what we call transient ischemic attacks as they had no method of expressing small units of time such as seconds or minutes. The distinction between a transient ischemic event and some epileptic seizures would have been difficult, as it can be today.

The modern psychiatrist will recognize an accurate description of an agitated depression, with biological features including insomnia, anorexia, weakness, impaired concentration and memory. The obsessive behavior described by the Babylonians included such modern categories as contamination, orderliness of objects, aggression, sex and religion. Accounts of psychopathic behavior include the liar, the thief, the troublemaker, the sexual offender, the immature delinquent and social misfit, the violent and the murderer.

A bas-relief of a wounded lioness from the Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, in the British Museum.

The Babylonians had only a superficial knowledge of anatomy and no knowledge of brain or psychological function. Although they had no knowledge of the spinal cord, the Babylonians and the Assyrians clearly understood that an arrow in the center of the back led to paralyzed hind legs, another important clinical observation (figure 2). They had no systematic classifications of their own and would not have understood our modern diagnostic categories. Some neuropsychiatric disorders, e.g., stroke or facial palsy, had a physical basis requiring the attention of the physician or asà», using a plant and mineral-based pharmacology. Most disorders, such as epilepsy, psychoses and depression, were regarded as supernatural due to evil demons and spirits, or the anger of personal gods, and thus required the intervention of the priest or aÅ¡ipu. Other disorders, such as OCD, phobias and psychopathic behavior, were viewed as a mystery, yet to be resolved, revealing a surprisingly open-minded approach.

From the perspective of a modern neurologist or psychiatrist, these ancient descriptions of neuropsychiatric phenomenology suggest that the Babylonians were observing many of the common neurological and psychiatric disorders that we recognize today. There is nothing comparable in the ancient Egyptian medical writings and the Babylonians therefore were the first to describe the clinical foundations of modern neurology and psychiatry.

A major and intriguing omission from these entirely objective Babylonian descriptions of neuropsychiatric disorders is the absence of any account of subjective thoughts or feelings, such as obsessional thoughts or ruminations in OCD, or suicidal thoughts or sadness in depression. The latter subjective phenomena only became a relatively modern field of description and enquiry in the 17th and 18th centuries AD. This raises interesting questions about the possibly slow evolution of human self awareness, that is central to the concept of “mental illness,” which only became the province of a professional medical discipline, i.e., psychiatry, in the last 200 years.

References

Kinnier Wilson JV, Reynolds EH. Texts and documents. Translation and analysis of a cuneiform text forming part of a Babylonian treatise on epilepsy. Med Hist. 1990; 34:185-98.

Reynolds EH, Kinnier Wilson JV. Stroke in Babylonia. Arch Neurol. 2004; 61:597-601.

Reynolds EH, Kinnier Wilson JV. Neurology and Psychiatry in Babylon. Brain. 2014; 137: 2611-2619.

Edward H. Reynolds is former consultant neurologist to the Maudsley and King’s College Hospitals; former director of the Institute of Epileptology, King’s College, London and former president of the International League against Epilepsy.

Peter J. Koehler is the editor of this history column. He is neurologist at Atrium Medical Centre, Heerlen, The Netherlands. Visit his website at www.neurohistory.nl