Maggie McNulty

In March 2015, a report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association to redefine the illness known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS).

Over the years, clinicians and researchers have developed different diagnostic criteria for ME and CFS; however, the two terms describe conditions with similar symptoms. In the World Health Organization’s “International Classification of Diseases,” 10th Revision, both ME and CFS are coded the same and classified as disorders of the nervous system (ICD G93.3). The term “benign myalgic encephalomyelitis” was first used in the 1950s in London when describing an outbreak in patients who experienced a variety of symptoms, including “malaise, tender lymph nodes, sore throat, pain and signs of encephalomyelitis.”

The cause was never found, but it appeared infectious in etiology, and the term “benign myalgic encephalomyelitis” was used to reflect “the absent mortality, the severe muscular pains, the evidence of parenchymal damage to the nervous system and the presumed inflammatory nature of the disorder.” Then in 1970, two psychiatrists reviewed reports of 15 of these outbreaks and concluded that the outbreaks “were psychosocial phenomena” caused by mass hysteria or altered medical perception of the community.

However, the idea that the condition was psychogenic in origin was refuted by Dr. Melvin Ramsay. In 1986, he was the first to publish diagnostic criteria for ME and, at this point, the term “benign” was dropped as the disease often was severely disabling for those patients afflicted. Around the same time, in the mid-1980s, there were two outbreaks of an illness that resembled mononucleosis characterized by “chronic or recurrent debilitating fatigue and various combinations of other symptoms, including sore throat, lymph node pain and tenderness, headache, myalgia and arthralgias.” This illness was at first linked to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV); however, further research ruled out this as the cause, and, in 1988, the term “chronic fatigue syndrome” was coined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

ME/CFS is characterized by symptoms of profound fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, sleep abnormalities, autonomic manifestations, pain and other symptoms that are worsened by any type of exertion. The syndrome affects women more than men with an average age of onset of 33 years with a wide range of distribution ranging from 10 to 77 years old.

ME/CFS is a common disorder that is currently estimated to affect 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans. Despite the prevalence of this disorder, less than one-third of medical school curricula and only 40 percent of medical textbooks include information regarding this syndrome. This likely contributes to delays in diagnosis time for these patients (e.g., 29 percent of patients report symptoms for >5 years prior to receiving a diagnosis), and it is estimated that 84 to 91 percent of people with this condition have not yet been diagnosed.

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.

In general, ME/CFS is a condition that is poorly accepted as its pathophysiological mechanisms are poorly understood, and many contest the characteristics needed to make a diagnosis. There continue to be many misconceptions regarding ME/CFS, including that it is a psychogenic illness. Many times, patient symptoms are met with skepticism or even dismissal. After diagnosis, many people with ME/CFS report being subject to hostile attitudes from their health care providers. The cause of ME/CFS is currently unknown; however, symptoms may be triggered by different infections or other prodromal events, including “immunization, anesthetics, physical trauma, exposure to environmental pollutants, chemicals and heavy metals and, rarely, blood transfusions.”

The IOM was asked by the Department of Health & Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Health Care Research & Quality, the CDC, the Food & Drug Administration and the Social Security Administration to convene an expert panel to review the evidence basis for ME/CFS. This was a comprehensive committee of 15 members that convened in September 2013 and took into account data from patients, clinicians and researchers while also reviewing almost 1,000 public comments. This was followed by a comprehensive literature review to help identify new diagnostic criteria to be used by clinicians. Based upon their work, a new name was recommended to replace ME/CFS. Previous studies have shown that the term “chronic fatigue syndrome” can negatively affect patients and medical professionals’ perceptions of the illness and trivialize the seriousness of the disease. “Myalgic encephalomyelitis” is also inappropriate as there is no evidence of encephalomyelitis in these patients, and myalgia is not a core symptom of this disease. The new name that has been recommended for use is systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID); this new name is felt to encompass the central characteristic of the disease: the fact that exertion of any kind can negatively affect patients in multiple different organ systems.

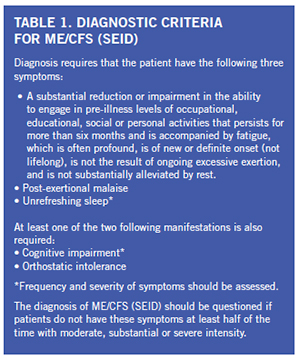

A new set of diagnostic criteria was also developed by the group with the intent to ease the process of making a diagnosis of ME/CFS (SEID) and hopefully, decrease the time to make a diagnosis for many patients. The new diagnostic criteria that were developed by the IOM committee are detailed in Table 1. The core features include: fatigue and impairment, post-exertional malaise (PEM) and unrefreshing sleep. All of these features need to be present for one to be diagnosed with ME/CFS (SEID).

Fatigue as defined in the dictionary is “weariness from bodily or mental exertion.” Sufficient evidence has been found that fatigue is profound in ME/CFS (SEID). Dramatic examples of reports of fatigue in patients with ME/CFS (SEID) include feeling “too exhausted to change clothes more than every 7-10 days” and experiencing “exhaustion to the point that speaking is not possible.” More commonly, patients report fatigue as “exhaustion, weakness, a lack of energy, feeling drained and an inability to stand for even a few minutes.” The fatigue must be associated with a significant reduction or impairment in the ability to engage in pre-illness levels of occupational, educational, social or personal activities. This degree of fatigue must also persist for more than six months.

Another core symptom, post-exertional malaise (PEM), is found consistently in patients with ME/CFS (SEID) and felt to help distinguish it from other conditions. A patient’s symptoms worsen after exposure to physical or cognitive stressors that were previously well tolerated prior to onset of the disease. Descriptions provided by patients after an exertional task include “crash,” “exhaustion,” “flare-up,” “collapse,” “debility” or “setback.” PEM may occur within 30 minutes of an exertional task or be delayed up to seven days after an exertional task with the duration of PEM lasting hours to months. In studies comparing ME/CFS (SEID) patients with healthy controls, 86 percent of patients report minimum exercise makes them tired compared to 7 percent of controls. Additionally, 85 percent of ME/CFS (SEID) patients report that they feel drained after mild activity compared to 2 percent of healthy controls.

The third and final core symptom is unrefreshing sleep for which 92 percent of ME/CFS (SEID) patients report compared to 16 percent of controls. The typical sleep-related symptoms described by ME/CFS (SEID) patients include difficulty falling asleep, frequent or sustained awakenings, early-morning awakenings and nonrestorative or unrefreshing sleep (persistent sleepiness despite adequate duration of sleep). Primary sleep disorders such as sleep-disordered breathing, restless legs syndrome and narcolepsy should be considered and evaluated for if clinically indicated as treatment of these disorders can be effective in reducing or relieving symptoms of unrefreshing sleep. However, a polysomnogram is not required to diagnose ME/CFS (SEID). Currently, there is no strong evidence to identify ME/CFS (SEID)-specific sleep pathology despite some studies revealing differences in sleep architecture in a subset of ME/CFS (SEID) patients compared to healthy controls.

In addition, there are two supportive criteria included in the new definition, of which one of two is required to be present to meet a diagnosis of ME/CFS (SEID). These include cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance. Common features of cognitive impairment that are seen in ME/CFS (SEID) include complaints of problems remembering, difficulty expressing thoughts, difficulty paying attention, slowness of thought, absent-mindedness and difficulty understanding. It is suggested that slowed information processing plays a central role in the cognitive impairment associated with ME/CFS (SEID). This deficit can lead to significant disability that results in loss of employment as well as functional capacity in social environments. Neuropsychological testing has found that patients with ME/CFS (SEID) display deficits in working memory compared with healthy controls with reduced verbal and visual memory being the most consistent finding. The second feature, orthostatic intolerance, refers to worsening of symptoms upon assuming and maintaining an upright position. Symptoms are typically improved but may not be alleviated by lying down or elevating their feet. There is sufficient evidence that indicates a high prevalence of orthostatic intolerance in patients with ME/CFS (SEID) based on bedside orthostatic vital signs, tilt table testing or by patient reported worsening of symptoms with standing in day-to-day life.

The committee also described additional frequent findings found in ME/CFS (SEID) patients, which include pain, immune impairment, infection and miscellaneous symptoms. Pain was found to be common in patients who had ME/CFS (SEID) with complaints of headaches, myalgias and arthralgias being most common. There was sufficient evidence found that supported the finding of immune dysfunction in these patients with data revealing poor NK cell cytotoxicity that correlated with illness severity in ME/CFS (SEID). This finding, however, is not specific to ME/CFS (SEID). Additionally, there was evidence that ME/CFS (SEID) can occur after infection with EBV, but there was not sufficient evidence to conclude that all cases of ME/CFS (SEID) are caused by EBV. Less frequent symptoms that were found in patients with ME/CFS (SEID) include gastrointestinal impairments, genitourinary impairments, sore throat, painful or tender axillary/cervical lymph nodes and sensitivity to external stimuli (e.g., foods, drugs, chemicals).

In summary, ME/CFS (SEID) is a serious, chronic, complex and systemic disease that often significantly limits the day-to-day activities of those affected. It is characterized by a prolonged, significant decrease in function; fatigue; post-exertional malaise; unrefreshing sleep; difficulties with information processing, especially under time pressure; and orthostatic intolerance. A thorough history, physical examination and targeted evaluation are necessary and can be sufficient to make a diagnosis. Despite the high prevalence of this condition with associated high economic burden, little research has been conducted to study the etiology, pathophysiology and effective treatment of this disease. Moving forward, it will be vital to distinguish this disease against other complex fatiguing disorders as the majority of previous research has compared ME/CFS (SEID) patients to healthy controls. Additional research into ME/CFS (SEID) is essential for further progress to be made, and the term “chronic fatigue syndrome” should no longer be used due to the associated stigma, which often precludes patients from receiving appropriate care. It is critical that we do our part to help stop the stigma associated with this condition and provide optimal care of these patients.