Mentions from the Bard raise questions about treatment during his time.

By Peter J. Koehler

Figure 1. William Shakespeare (1564-1616), engraving by Martin Droeshout (public domain).

Awhile ago, I was asked to collaborate on a podcast about migraine in William Shakespeare’s time. Although I had written about the history of migraine not long ago, it inspired me to delve deeper into this particular period. How was migraine defined or diagnosed, and what treatments were available? There are a number of articles and chapters in medical literature about neurology, headaches in particular, in the works of Shakespeare.1,2,3

Shakespeare and His Son-in-Law

English playwright and poet William Shakespeare (1564-1616, see Figure 1) was born in Stratford-upon-Avon and is known as the “Bard of Avon.” He wrote a vast body of work that includes no fewer than 39 plays and 154 sonnets. He married 26-year-old Anne Hathaway (1556-1623) in 1582, when he was 18 years old. They had three children, of whom the oldest, Susanna (1583-1649) married a local physician named John Hall (1575-1635). Hall studied at Queen’s College Cambridge (BA 1593, MA 1597). However, he had no English medical degree and probably received medical training on the continent. This was possibly in France, as he was “a traveler acquainted with the French tongue.”

Hall established himself in Stratford around 1600 and is often claimed to be the source of medical information in Shakespeare’s writings, although about half of his plays were written before Hall came to Stratford. Shakespeare wrote about medical issues before meeting Hall, but he did not write about physicians. This changed after 1605. Neurologist John M.S. Pearce wondered, “Do these, taken together, represent an affectionate and admiring sketch of his son-in-law, John Hall?”4

Figure 2. Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893), whose bicentennial of birth is being celebrated this year. (© The National Library of Medicine believes this item to be in the public domain; see [Jean Martin Charcot] – Digital Collections – National Library of Medicine.)

Charcot’s Interest in Shakespeare

There is another interesting relationship between Shakespeare and neurology. It is well known that Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893, see Figure 2) was particularly interested in Shakespeare’s work. (This year, we are celebrating the Charcot bicentennial with a special meeting of the International Society for the History of Neurology (ISHN) in Paris and with a special issue of the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences.*)

Quotes from the famous poet are referenced in several places, including in the book Charcot: Constructing Neurology and the chapter “The Influence of Shakespeare on Charcot’s Neurological Teaching.”5,6 In the chapter, we learn about Charcot’s Anglophilia and his “incorporation of Shakespearean citations into his neurological teaching [that] served several purposes.” Charcot’s biographer Christopher Goetz, the author of the chapter, writes: “Occasionally, he drew on Shakespeare’s words to illustrate a specific neurological observation. More often, he lauded Shakespeare as an exemplary observer of human behavior and emphasized the clinical importance of careful and dispassionate documentation.” Furthermore, Charcot “used Shakespeare’s words to communicate philosophical principles related to the field of medicine and the role the physician.”6

An interesting aspect mentioned by Goetz is that Charcot appreciated “the particular mixture of the real and the unreal” in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. This was related to Charcot’s study of hysterics from 1878 onward and “the spectacular behaviors of the hysterics who crowded his wards, and whose symptoms were often mixtures of real and elaborated disease.” These patients “often unwittingly mimicked the witches and spirits of the Shakespearean stage.”6 We also find information on a tableau of Macbeth rendered by Charcot’s children Jeanne and Jean, as well as his students.5

Headache in Othello and Migraine in Romeo and Juliet

Figure 3. Title page of Philip Barrough’s Method of Physic (sixth edition of 1624).

Among Shakespeare’s best known tragedies are Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, Othello, and Romeo and Juliet. In the latter two plays, headache and migraine are mentioned. In The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice (Act III, scene 3), the protagonist, who is falsely manipulated with insinuations that his wife is unfaithful to him, says: “I have a pain upon my forehead here,” upon which his wife Desdemona answers, “Faith, that’s with watching; ‘twill away again: Let me but bind it hard, within this hour it will be well.”

In Act II, scene 5 of The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, the nurse, Juliet’s personal attendant and confidante, who secretly contacted Romeo, says, “Lord, how my head aches! What a head have I! It beats as it would fall in 20 pieces.”

Philip Barrough’s Method of Physic

If we want to understand the knowledge about headaches and migraines at that time, we must realize that physicians were still thinking in terms of the humoral medicine of antiquity (Galenic medicine). Frequent references were made to Galen (129-c. 216) and Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 370 BCE). Health and disease depended on the proper balance of body fluids, including blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile.

A good example from the period of Shakespeare would be the first edition of Method of Physic (1583, see Figure 3), by London surgeon and physician Philip Barrough, who wrote in terms of Galenic medicine. He obtained his license to practice surgery from the University of Cambridge, and in 1572, he was licensed to practice physic. He probably practiced in London.7 His book was dedicated to “Lord and Master the Lord Burgley, High Treasurere of England,” thereby pointing to William Cecil, first Baron of Burgley (1520-1598).

Looking at the 1624 sixth edition, the book follows the usual sequence a capite ad calcem (from head to heel) and starts with diseases of the head. The book seems to have been popular as it reached at least seven editions, with the last being published in 1652. The first 12 chapters deal with headache, and Chapter 13 deals with migraine. (See Figure 4.) The chapters on headache are typical of the period, describing headache caused by heat, cold, dryness or moistness, blood, choler, and phlegm, but also by drunkenness. After Chapter 13, some other “neurological” conditions are described, including frenzy, lethargy, “losse of memorie,” “carus or subeth” [deep sleep], paralysis, apoplexy, cramp, madness, melancholy, trembling, and shaking.8 These “neurological” subjects comprise 29 chapters in 48 pages.

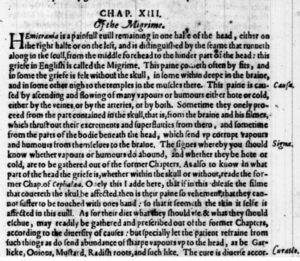

Figure 4. Chapter 13 on migraine of Philip Barrough’s Method of Physic (sixth edition of 1624).12

Barrough’s book is said to be the first medical book in English. Indeed, at the time, many medical books were still published in Latin. For instance, the book De cerebri morbis (1549) by Jason Pratensis (1486-1558) is in Latin. In this book, the first seven chapters are on headache with titles similar to Barrough’s book, and Chapter 8 is on “hemicrania.”

Barrough first gave general information on headache in his 1583 book on medicine. “Cephalgia is nothing else but a laboriouse and painefull sense, and feeling newly begonne in the whole head, through some great mutation thereof, this word newly is added to make it differ from Cephalaea, which is an old paine that hath long continued: and the whole head is added to make it differ from Hemicrania, which occupieth but the one half of the head.”

This in fact is not much different from the classification given by Areataeus of Cappadocia (second century).9,10 For migraine, Barrough used the terms hemicrania, in English migrime. “Hemicrania is a painefull evill remaining in the one halfe of the head, either on the right halfe or on the left, and is distinguished by the seame that runneth along in the skull, from the midde forehead to the hinder parte of the head, this griefe in Englishe is called the Migrime. This paine cometh often by fittes, and in some the griefe is felt without the skull, in some within deepe in the braine, and in some other nigh to the temples in the muscles ther.”

In his definition, it was localized on one side of the head. He believed this was due to the falx cerebri. He described symptoms, including pain on one side of the head, often periodic (fits), felt on the skull or deep in the brain, sometimes the temples. As for the pathophysiology, he wrote in terms of vapors rising, hot or cold, and if the meninges are involved, it can be very painful, with the patient barely able to touch the skin.

As for the treatment, he wrote, “The patient should refrain from such things as do send abundance of sharp vapors up to the head (garlicke, oynions, mustard, raddishe rootes, and such like).” The physician was expected to cure the migraine, and first consider diligently whether the patient needed bloodletting or purging. This was followed by local and external remedies depending on whether there was an abundance of cold or hot humors. The patient should rub either their own fingers or a linen cloth over the half of the forehead that is hurt, and specially over the muscles of the temples, until it is red and hot.

Of course, Shakespeare did not give much information about the symptoms of his characters’ headaches. Although it is hazardous to make a diagnosis based on so little information from the 16th century, the “pain in the forehead” of Othello, could have been a tension-type headache. The description of the headache — [the head] “beats as it would fall in 20 pieces” — of Juliet’s nurse suggests migraine. Shakespeare also gave no information about treatment, other than “Let me but bind it hard.” And the information he gave would not have required reading medical writings. •

Peter J. Koehler, PhD, is co-editor of the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. He has won several awards, including the Lawrence C. McHenry Award of the AAN and the Lifetime Achievement Award for the International Society of the History of the Neurosciences. He is currently affiliated with the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands. His recent books focus on art history (The Stone of Madness. Art and History) and on the enlightened naturalist Philippe Fermin (1730-1813).

* Information on the ISHN Charcot bicentennial (1825-2025) meeting in Paris can be found on the ISHN home page (including information about ISHN membership) and in the special issue on Charcot of the associated Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, which is not only the official journal of the ISHN, but also of the World Federation of Neurology (WFN) History of the Neurosciences Specialty Group.

References:

- Paciaroni M, Bogousslavsky J. William Shakespeare’s neurology. Prog Brain Res. 2013;206:3.

- Gomes Mda M. Shakespeare’s: his 450th birth anniversary and his insights into neurology and cognition. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2015 Apr;73(4):359-61.

- Matthews BR. Portrayal of neurological illness and physicians in the works of shakespeare. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2010;27:216-226.

- Pearce JM. Dr John Hall (1575-1635) and Shakespeare’s medicine. J Med Biogr. 2006 Nov;14(4):187-91.

- Goetz CG, Bonduelle M, Gelfand T. Charcot. Constructing Neurology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Goetz CG. The influence of Shakespeare on Charcot’s neurological teaching. In: Rose FC (ed). Neurology of the Arts. London, Imperial College Press, 2004, pp. 329-36.

- Stephen L. Dictionary of National Biography. Barrow, Philip. Vol. 3, New York, Macmillan, 1885, p. 308.

- Barrough P. The methode of phisicke conteyning the causes, signes, and cures of invvard diseases in mans body from the head to the foote. VVhereunto is added, the forme and rule of making remedies and medicines, which our phisitians commonly vse at this day, with the proportion, quantitie, & names of ech [sic] medicine London, Thomas Vautroullier, 1583.

- Koehler PJ, van de Wiel TW. Aretaeus on migraine and headache. J Hist Neurosci. 2001 Dec;10(3):253-61.

- Koehler PJ, Boes CJ. History of migraine. Handb Clin Neurol. 2023;198:3-21.

- Shakespeare W. Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, London, Jaggard & Blount, 1623.

- Barrough P. The methode of phisicke etc. 6th edition. London, Field, 1624.