A tale of two brothers and one cookbook.

By Peter J. Koehler

Figure 1. Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière by André Brouillet (1887), oil on canvas, Paris, Musée de l’histoire de médecine.

In the introduction of a relatively well-known French cookbook, we find the following text: “Les principes fondamentaux de l’art culinaire sont très simples. (The basic principles of the culinary arts are very simple.)” Looking through the book, I doubt the recipes described are that simple. However, it is an interesting cookbook as it relates to neurology.

Two Brothers

The story begins in 1848, a year in which several revolutions took place in Europe, including in Poland. Fleeing this revolution, a Polish couple moved to Paris the following year, where two sons — Henri and Joseph — were born in 1855 and 1857, respectively. Henri attended the École des Mines, after which he worked in South America for about 20 years. After their parents’ deaths in the late 1890s, he returned to Paris and shared an apartment with his younger brother.1

Figure 2. Babinski sign from Arthur van Gehuchten’s 1908 film10 (the Belgian neurologist Van Gehuchten was the first to use the eponym in 1898).11

Meanwhile, Joseph studied medicine and served internships in various Parisian clinics during the 1880s. From November 1885 to October 1887, he was chef-de-clinique at the Salpêtrière under Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893), whose bicentennial will be celebrated in July 2025 in Paris. He also met Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who visited Charcot during the winter of 1885-1886 and translated two of Charcot’s books into German.2 This was the period during which Charcot showed particular interest in the condition then called hysteria.3

Joseph, who later disagreed with his teacher about the condition, is depicted in the famous portrait from that clinic. (See Figure 1.) He is the bearded young man catching one of the patients, Blanche Wittmann (1859-1913) in his arms. The Norwegian writer Per Olov Enquist (b. 1934) wrote a novel about Blanche not long ago: The Story of Blanche and Marie (2004). A study on Blanche and other patients was published by Asti Hustvedt,4 the sister of novelist Siri Hustvedt, who referred to Charcot and the Salpêtrière in her novel What I Loved. Several famous people are depicted in the painting, including Pierre Marie, Georges Gilles de la Tourette, Henri Parinaud, and Désiré-Magloire Bourneville.5

Pathological Plantar Reflex

In 1890, Joseph became médecin des hôpitaux, and beginning in 1895, he worked as a neurologist at Hôpital de la Pitié. He was one of the neurologists who described several components of current neurological examination,6,7,8 the most famous of which is the pathological plantar reflex. It was named after him: the Babinski plantar sign (1896).9

At a time when there was no CT or MR scan — even pneumoencephalography and arterial encephalography had to wait a few decades12 — it was even more important than today to use this to distinguish organic paralysis from hysterical paralysis as it was then called. Nowadays, we would call it a functional disorder.13

Figure 3. Gastronomie Pratique by Ali-bab, first edition of 1907.

Surréalism

Joseph played an important role in the life of André Breton (1896-1966), the French poet and founder of surrealism. From January to September 1917, Breton worked as a student under Babinski at La Pitié. He ultimately did not take exams to become a physician. The Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 includes the following passage on this subject:

“I have seen the inventor of the cutaneous plantar reflex at work; he manipulated his subjects without respite, it was much more than an “examination” he was employing; it was obvious that he was following no set plan. Here and there he formulated a remark, distantly, without nonetheless setting down his needle, while his hammer was never still. He left to others the futile task of curing patients. He was wholly consumed by and devoted to that sacred fever.”

Besides neurology, Joseph had an interest in music and drama. He would often be seen at the Paris Opéra. In 1956, Breton revealed that Babinski was one of the authors of the play Les Détraquées (1920) written by Pierre Palau (1883-1966) “with Olaff’s help.” Olaff turned out to be a pseudonym of Joseph Babinski.14

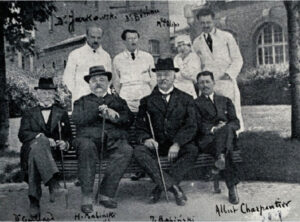

Figure 4. Henri is smaller and more corpulent than Joseph Babinski.

Gastronomy

After suffering hardships in the interior of South America, Henri Babinski returned to Paris and moved into a bachelor apartment — at one point, the brothers lived on Boulevard Haussmann — to devote himself to cooking. The two brothers became inseparable. Joseph’s student Clovis Vincent (1879-1947), who later became a pioneer of French neurosurgery, wrote of them, “His brother and Joseph had a veritable cult for each other, which never waned. Joseph lived for his career and for science; Henri lived for Joseph. Without Henri, Joseph would ultimately have achieved much less.”1

Henri’s interest in gastronomy led to a second career. In 1907, he published Gastronomie Pratique, which was subsequently republished several times, even as recently as 2013.

Henri was smaller than his brother Joseph and corpulent. (See Figure 4.) The full title of the book is probably related to this: Gastronomie pratique. Études culinaires suivies du Traitement de l›Obésité des Gourmands (Practical Gastronomy. Culinary Studies Followed by Treatment of Obesity in Gourmands). Regarding the latter, Henri noted in the introduction, “Tous mes amis connaissent l’ancien obèse sujet principal de mon expérimentation; ils sont prêts à témoigner de la réalité de la cure, comme ils sont prèts à attester les qualités de ma cuisine. C’est sous leurs auspices que je présente ce petit livre au public. (All my friends know the former obese subject of my experimentation; they are willing to testify to the reality of the cure, just as they are willing to testify to the qualities of my cooking. It is under their auspices that I present this little book to the public.)”

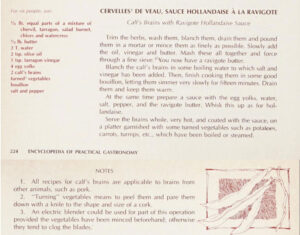

Figure 5. English-language edition of Henri Babinski’s cookbook.

Ali-bab

Why Henri chose the pseudonym Ali-bab is not exactly known. Possibly “Ali” stands for “the other” Babinski, but several alternative possibilities have been mentioned.1 The book was successful, given its many editions, and was widely acclaimed. A specialist in gastronomic literature, Gérard Oberlé (b. 1945), in his Les Fastes de Bacchus et de Comus, ou histoire du boire et du manger en Europe de l’Antiquité à nos jours, à travers les livres (The Annals of Bacchus and Comus, or the history of eating and drinking in Europe from antiquity to the present day, through books), wrote the following about Gastronomie Pratique: “one of the most famous recipe collections of the 20th century. … Contrary to what he claims in the preface, not everyone is up to the challenge of Babinski’s dishes. You have to be quite well-off to afford the ingredients and be well versed in the art of cooking. Lots of truffles, fat capons, sauterne sauces, and foie gras.”

An enjoyer of the culinary life, Ali-bab, or Henri, wrote on the last page of his book, “ … s’il est indécent de vivre pour manger, il convient, tout en mangeant pour vivre, de chercher à s’acquitter de cette tâche, comme de toutes les autres, de son mieux, avec plaisir (… if it is indecent to live to eat, it is advisable, while eating to live, to try to perform this task, like all others, to the best of your ability, with pleasure).”

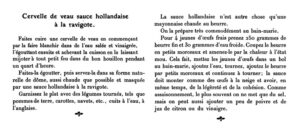

Figure 6a. Cervelle de veau sauce hollandaise à la ravigotte.

On the occasion of my PhD on a medical history topic in 1989, I received a copy of Gastronomie Pratique from my teacher Lambertus J. Endtz (1927-1989). Although I must confess that I have never used a recipe from the book — after all, I do not have that gift that Ali-bab mentions in the introduction: “les cuisiniers habiles voient le moment précis où la cuisson est à point, ils ont l’instinct des proportions de condiments qu’il convient d’employer. (skilled cooks who see the exact moment when a dish is perfectly cooked and have an instinct for the right proportions of the condiments to be used.)”

I want to challenge readers to take a look at this book. Although it is still sold in bookstores, it is also available for download from the internet.15 There is even an English-language edition, in fact enlarged to become an encyclopedia. (See Figure 5.)16

Figure 6b. Cervelle de veau (uit de Engelse editie).

Brains and Truffles

The following recipe may be something his brother Joseph enjoyed: Cervelle de veau sauce hollandaise à la ravigotte (Calf’s brains with hollandaise sauce à la ravigotte).8 (See Figure 6a.)

Figure 7. Filets de levraut rôtis sauce aux truffes.

In the English edition, I found the following translation. (See Figure 6b.)

Should you manage to get your hands on truffles — at the Alba auction in Piedmont, Italy, they go for several tens of thousands of Euros17 — I can recommend Filets de levraut rôtis sauce aux truffes (roasted young hare fillets with truffle sauce.)(See Figure 7.)

I was unable to find this dish in the English translation. Fortunately, it contains many other dishes that may be easier to prepare today, such as Pot-au-feu de famille, which Gastronomie Pratique begins with. •

References:

1. Philippon J, Poirier J. Joseph Babinski. A Biography. Oxford University Press, 2009.

2. Koehler PJ. Freud’s comparative study of hysterical and organic paralyses: how Charcot’s assignment turned out. Arch Neurol. 2003 Nov;60(11):1646-50.

3. Goetz CG, Bonduelle M, Gelfand T. Charcot: Constructing Neurology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

4. Hustvedt A. Medical Muses. Hysteria in Nineteenth Century Paris. London, Bloomsbury, 2011.

5. See SHMR-95: Le docteur Joseph Babinski (shmr95.fr); accessed October 5, 2024.

6. Okun MS, Koehler PJ. Babinski’s clinical differentiation of organic paralysis from hysterical paralysis: effect on US neurology. Arch Neurol. 2004 May;61(5):778-83.

7. Koehler PJ, Okun MS. Important observations prior to the description of the Hoover sign. Neurology. 2004 Nov 9;63(9):1693-7.

8. Voogd J, Koehler PJ. Historic notes on anatomic, physiologic, and clinical research on the cerebellum. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;154:3-26.

9. Van Gijn J. The Babinski sign: a centenary. Utrecht University, Publication Department.

10. Aubert G. Arthur van Gehuchten takes neurology to the movies. Neurology. 2002 Nov 26;59(10):1612-8.

11. Van Gijn J. Babinski’s sign. In: Koehler PJ, Bruyn GW, Pearce JMS. Neurological Eponyms, New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 117.

12. Lutters B, Koehler PJ. Cerebral pneumography and the 20th century localization of brain tumours. Brain. 2018 Mar 1;141(3):927-933.

13. Stone J. Neurologic approaches to hysteria, psychogenic and functional disorders from the late 19th century onwards. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:25-36.

14. Haan J, Koehler PJ, Bogousslavsky J. Neurology and surrealism: André Breton and Joseph Babinski. Brain. 2012 Dec;135(Pt 12):3830-8.

15. Original French edition of 1907 : Gastronomie pratique: études culinaires suivies du Traitement de l’obésité…: Ali-Bab: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive

16. Engelse editie uit 1973: The encyclopedia of practical gastronomy: Ali-Bab, 1855-1931: Free Download, Borrow, and StreamingInternet Archive; accessed November 10th, 2024.

17. Alba White Truffle World Auction (castellogrinzane.com); accessed November 10th, 2024.