By Peter J. Koehler

Peter J. Koehler

Considering that book printing was invented in the early 15th century (Johannes Gutenberg, Mainz, Germany) and the copying of texts before that period had to be done by hand, one wonders whether writer’s cramp has been described in the middle ages.

As far as I now, it has not been referred to before the description by the Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini (1633-1714) who, in 1713, published a book on occupational diseases and since then has been considered the father of occupational medicine. His book De Morbis Artificum Diatriba (Diseases of Workers) indeed contains a large number of occupations with associated disorders. In the chapter “Diseases of Secretaries, Clerks, Writers and Copyists,” Ramazzini started to refer to the ancients, who had more copyists and writers than in his days, and to the Roman writer and naturalist Pliny, who, on his journeys, was usually accompanied by a writer with a book and tablets.

Bernardo Ramazzini

In Ramazzini’s own environment, secretaries and clerks of princes, magistrates and merchants were paid to keep the books, and registers and were “subject to several diseases that depend either to the sitting position that they are obliged to conserve for long periods, or from the continuous movement of the same hand, or finally from the mental effort necessary not to make errors in their calculations.”1 He continued to describe the necessity to hold the quill continuously and move it for writing, and that it fatigues the hand and even the whole arm, due to the continuous contraction of the muscles. Ramazzini was acquainted with a writer, who had been writing his entire life, by which he had gathered some fortune. He experienced at first a considerable lassitude in his whole arm that resisted against all kinds of remedies, and that ended in a complete paralysis of that arm. He taught himself to write with his left hand, but, after some time, the arm became afflicted with the same disease.

Bernardo Ramazzini’s De Morbis Artificum Diatriba (Diseases of Workers)

Ramazzini added that the mental efforts, to which clerks are subject, may result in migraines, colds and swelling of the eyes. To prevent these diseases, the author advised to do exercises in the evening and during holy days. Interestingly, he also wrote that “the use of tobacco may diminish their headaches,”1 and for the paralysis of the hands, they should wash them with aromatic wine or liquors.

The well-know Scottish surgeon Charles Bell — of Bell’s palsy — may have presented an early observation in the 1833 edition of his Nervous System of the Human Body,2 where, under the title “Partial Paralysis of the Muscles of the Extremities,” he wrote that it is an obscure object … an affection of the muscles which are naturally combined in action.” Bell found the action necessary for writing gone, or the motions so irregular, as to make the letters be written in zigzag, while the power of strongly moving the arm, or fencing, remained.

Charles Bell

In German language, the disease was referred to as mogigraphie and schreibekrampf. Georg Hirsch, physician at Königsberg, was among the early German authors on the subject. “The most particular form of partial abnormal muscle movement is the writer’s cramp, for which I propose as technical name mogigraphia, in analogy to Mogilalia.”3

The extraordinary disease could not be localized in the muscles, but was believed to arise from a general nerve irritation that is only present in muscles fatigued after much writing. The thumb and secondly the index finger are most often involved, with the text noting the illness is described easily as shaking, or as stiffness, mostly as a hasty flexion movement. He also referred to Moritz Reuter, who told about a 30-year-old famous composer “to whom, since 10 years, every time when playing the piano, the right middle finger fails by upcoming spasm,” possibly referring to Robert Schumann.3 The origin of writer’s cramp was thought to be in the spinal cord (hence the book’s name, spinal neurosis), and a section of a tendon was sometimes suggested.

Georg Hirsch’s chapter on mogigraphie

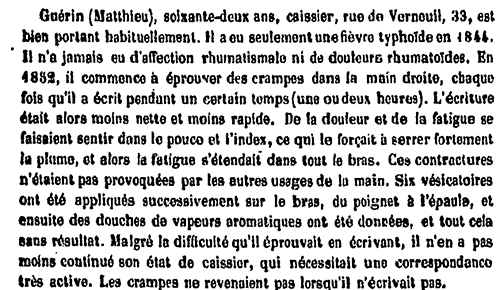

Guillaume B.A. Duchenne de Boulogne, the well-known French physician, who used to visit Paris hospitals to apply electric therapy for all kinds of diseases, described several cases of writer’s cramp in his De l’électrisation Localisée.4 Case 213, Matthieu Guérin, age 62, was a cashier, who, in 1852, started to complain of cramps in his right hand each time when he wrote for a certain period of time. He suffered from pain and fatigue in his thumb and index finger, which forced him to hold the quill tightly. The fatigue would spread through his entire arm. He did not experience any symptoms when using his hand for other tasks. He was treated by six vesicatories and by douches with aromatic vapors without any relief. Two years later he was not able to hold the quill anymore, and he had taught himself to write with his left hand.

Charles Bell’s The Nervous System of the Human Body (1833 American edition)

Then he started to suffer from spasms in his right shoulder and neck, at first only when writing, but later continuously. At last, he was forced to give up his job as a cashier. In 1859, he presented at the clinic of Auguste Nélaton, where Duchenne was consulted. He treated the patient with electricity and an apparatus to keep his head to the other side. “Aujourd’hui, aprè

s la quinziè

me séance, le malade peut àªtre consideré comme guéri,” which means he was cured from the cervical dystonia following the 15th treatment session, but the writer’s cramp did not disappear.4

Guillaume B.A. Duchenne de Boulogne

Introducing other cases of crampe des écrivains, he wrote that the affliction was known in Germany with the name schreibekrampf. He had noticed that the muscles involved could vary. In a stockbroker, he observed flexion of the index finger as soon as he had written a few words. In an office worker at the war ministry, the first two fingers took an opposing position upon writing. Duchenne also saw supination of the hand. The treatment of what he called spasme fonctionnel was usually disappointing. He applied local faradisation during 12 years in 30 or 35 cases, but only saw two successful cases.

Duchenne’s De l’électrisation Localisée (Second edition, 1861)

Duchenne also observed a case of primary writer’s tremor, noting that “Mr. X … , lawyer, 26 years old … writing about three hours a day, was affected, in the course of the month of January 1860, by tremors of the right hand, with trouble making letters. … Even the idea of writing seems to lead to tremor, that also increases when someone is looking at it. … The tremor is provoked by no other use of the hand than that of writing.”4

Duchenne’s case 213, Matthieu Guérin

Obviously, writer’s cramp has been a disorder that existed for centuries, has been described in many countries and most probably already existed prior to Ramazzini’s description. Perhaps other than (medical) sources should be consulted to find them.

Duchenne’s patient treated with an apparatus to keep his head to one side

- Patissier Ph. Traité des Maladies des Artisans et Celles que résultent des diverses professions, d’aprè

s Ramazzini. Paris, Bailliè

re, 1822. - Bell C. Nervous system of the human body. Washington, Green, 1833, p. 221, case no. 86.

- Hirsch G. Beiträge zur Erkenntnis und Heilung der Spinal-Neurosen. Königsberg, Bornträger, 1843, p. 430.

- Duchenne GB. De l’à‰lectrisation localisée et de son application à la physiologie, à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique. 2nd ed. Paris, Balliè

re, 1861.