Exploring the connection between neurology’s past and the artistic movement.

Peter J. Koehler

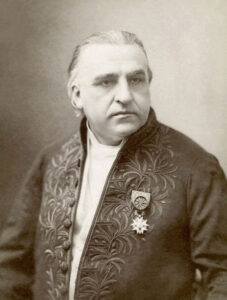

Figure 1. Jean-Martin Charcot (© NIH / U.S. National Library of Medicine).

This year, attention to the bicentennial of the birth of one of the founders of neurology, Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893, see Figure 1) will be given in several places. There will be a special issue of the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, covering topics around Charcot that have so far gone unmentioned. Many aspects of Charcot’s career and his interest in art have been described in the past or will be discussed in the special issue.

The book Charcot: Constructing Neurology noted, “Charcot’s tastes in art and literature revealed a preference for order and logic, but a fascination as well with the fantastic and bizarre.”1 The authors said he was “a severe critic of Modern Impressionism,” and he was “fond of the Flemish and Dutch school,” a preference that is understandable after reading the book. In terms of art history, however, there is more to say about this, in particular, an interesting story about an association between Impressionism and the Salpêtrière School.

Figure 2. Jan Steen, Marriage at Cana, 1676, oil on canvas, 79.7 x 109.2 cm, Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum. (© The Norton Simon Foundation).

Charcot’s Taste for Art

In his often-quoted article “Charcot Artiste,”2 Henry Meige (1866-1940), former pupil of Charcot and future professor of anatomy at the Paris Ecole des Beaux-Arts, wrote, “with his penchant for naturalistic simplicity, Charcot did not particularly like the innovations of modern art. The complex, the elaborate, the contrived left him cold, as did the murky, the ‘imprecise,’ the ‘vague’.” And Meige continued: “He was very severe about the paintings of the Symbolists and Impressionists, and even found the praise heaped on Corot (Jean-Baptiste Camille; 1796-1875) excessive; and having had the opportunity to part with a painting by this master, he did so without regret. At no price would he have agreed to part with a Jan Steen (1626-1679).”

Figure 3. Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872, oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm, Muséé Marmottan Monet, Paris (© Musée Marmottan Monet).

Indeed, Charcot and his wife Victoire Augustine Laurent (1834-1899), who was a daughter of the wealthy Paris art collector Charles Vincent Claude Laurent (1811-1886), known as Laurent-Richard, owned one of seven existing versions of Marriage at Cana by Jan Steen (1676, see Figure 2). It was sold a year after Madame Charcot’s death in 1900. In the 1930s, it was bought by the well-known Amsterdam Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker (1897-1940). After he fled to England in May 1940, the entire collection of over 1,000 works was purchased by the Nazi Hermann Göring (1893-1946) and the German banker turned Dutch art dealer Alois Miedl (1903-1970) for a fraction of its actual value. After World War II, the Jan Steen painting came back to the Netherlands. It was later bought by the Norton Simon Foundation in Pasadena, California, where it is now displayed.3 The Norton Simon Museum narrowly escaped the recent fires in the Los Angeles area.

Impressionist Art Born of Illness?

The story of Impressionism is well known. It played out at a time when Charcot was teaching about hysteria at the Salpêtrière. A group of artists established a cooperative enterprise named “Société anonyme cooperative à capital variable des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et lithographes (Cooperative limited company with variable capital for artists, painters, sculptors, engravers, and lithographers)” with the aim of organizing free exhibitions. Members included the painters Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne and Berthe Morisot.

Figures 4a and b. Le Charivari of

April 25, 1874, including Leroy critical piece on 1874 exhibition.

Although they are well known today, this group had often been rejected for the official annual Paris Salon, where the Académie des Beaux-Arts had great influence. A new Realist Salon for their work was organized in 1874. One of paintings submitted was Claude Monet’s Le Havre: Fishing Boat Setting Sail (1872). Journalist Edmond Renoir (1849-1944; brother of the painter Auguste) made the catalog and suggested an alternative title, because of the canvas’s hazy and indefinable nature: Impression, Sunrise. (See Figure 3.) The artist and critic Louis Leroy (1812-1885) gave a satirical description of the exhibition in the illustrated journal Le Charivari and used the title of his article “Exhibition of the Impressionists” for this reason, with a negatively intended connotation. However, the term was soon adopted by other art critics. (See Figure 4).4 The Realist Salon became the First Impressionist Exhibition.

Critics of the time derided Impressionist paintings as the product of disability and described them in terms of unfinished or bold works. Some influential critics called it an undermining of social and artistic norms or considered it a form of illness or even madness. Ophthalmic and psychological conditions were frequently suggested. At the Second Impressionist Exhibition (1876), a critic for the conservative newspaper L’Écho Universel wrote about “the brilliance of daylight, the purity of atmosphere, and the blue of water and sky,” but added that Monet might be a dazzling landscapist if only he could be cured of the “sickness of Impressionism.”5

It was noticed that some of the painters often applied an unnatural blue-violet color. In 1878, for instance, journalist and art critic Théodore Duret (1838-1927) wrote, “winter has come, the impressionist paints snow, he sees that in the sun the shadows cast on the snow are blue he paints blue shadows without hesitation, so the audience laughs out loud.” When discussing a painting by Édouard Manet (Portrait of Mr. Pertuiset, The Lion Hunter, see Figure 5), writer Jules Claretie (1840-1913), a friend of Charcot, who is shown on the famous painting Leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière, wrote, “I finally discovered the true color of the atmosphere. It’s purple. The outdoors is purple. I’ve found it! In three years from now, everyone will be purple!”

Another critic wrote that the public “has decided that the proper role of the Impressionist is to paint red trees, pink grass, and lilac skies.” In fact, critics accused the Impressionists of suffering from several forms of dyschromatopsia, including color blindness. Another idea was that these painters could see colors invisible to normal persons. Yet another critic suggested that the “invisible part of the spectrum is keenly felt by some people. M. Monet is certainly one of them. He and his friends see violet, the crowd sees otherwise; hence the disagreement.”

In her recent study, Alessandra Ronetti, a scholar in art history, noted: “The question of the colors adopted by modern painters is progressively linked to a pathologization of the artist’s body.”6

Figure 5. Edouard Manet, Portrait of Mr. Pertuiset, The Lion Hunter, 1881, oil on canvas,

150 x 170 cm, Museum of Art Sao Paolo (MASP), Brazil (© MASP).

Linking Charcot to Impressionism

Participating in the debate about these paintings was the French author Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), who played a role in the recent novel Soumission (2015) by the French writer Michel Houellebecq. Huysmans may have suffered from the popular disease of the time, nervous exhaustion (neurasthenia), and from neuralgia in 1881. His novel following this period, A Rebours (1884; translated as Against the Grain), has been considered the French brevier of the Decadent Movement, comparable to Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).7 Huysmans, whose father was Dutch, was a great lover of “the divine Rembrandt.” Not coincidentally, the eccentric protagonist Des Esseintes of A Rebours takes some of Rembrandt’s engravings with him to the house, in which he intends to entrench himself against modernity.8

Huysmans made the link between the modern paintings with the symptoms Charcot observed in patients suffering from hysteria. We do not know whether he attended Charcot’s lectures at the Salpêtrière as many other writers did, including Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) and Jules Claretie, but he was aware of Charcot’s lectures. Perhaps this was related to his retreat to convalesce at Fontenay-aux-Roses in 1881. The house became a model for that of the neurotic Des Esseintes, the main character in his novel A Rebours.9 Huysmans’ biographer Robert Baldick (1927-1972) believed he was “suffering severely from attacks of neuralgia.”10

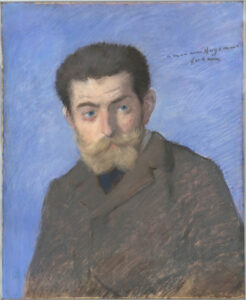

Another connection could be the prolonged illness of his mistress Anna Meunier, who was once diagnosed with “neurosis” and later died from general paralysis of the insane.10 Charcot and his clinic had an important influence on Huysmans11 and played a role in his novel Là-bas (1891; translated as Down There).7 Huysmans wrote about Charcot’s observations “of alterations in color perception that he had noted in hysterics at the Salpêtrière and in many people suffering from diseases of the nervous system.” He also mentioned ophthalmologist Xavier Galezowski (1832-1907), who had worked at the Salpêtrière and to whom Charcot often referred, and his ideas about the loss of seeing green by atrophy of certain retinal nerve fibers.12 In a later period, Huysmans (see Figure 6) became more positive and even defended Impressionism. He was portraited by Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), who was an Impressionist painter in his early career.

Figure 6. Jean-Louis Forain, Joris-Karl Huysman [his friend], 1878, pastel, 55 x 44.5 cm (© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski).

Charcot on Dyschromatopsia in Hysterical Cases

Charcot often indicated vision problems in hysterical patients. On one occasion, when discussing visual field disorders, he said: “J’ai peut-être examiné des milliers de fois le champ visuel des hystérique et je tiens à le proclamer une fois de plus puisque l’occasion s’en présente; c’est toujours l’amblyopie double plus prononcé du côté hémianaesthésie ou unilatérale…(I may have examined the visual field of hysterics thousands of times, and I want to proclaim it once again as the opportunity arises: It is always double amblyopia, more pronounced on the hemianesthetic or unilateral side.)”13

In his lectures on hysteria, one of the frequent symptoms he spoke of was hysterical achromatopsia or dyschromatopsia. Probably the first lecture in which he referred to hysterical achromatopsia was given in 1872. In lecture X, “Hysterical Hemianaesthesia,” we find: “Vision is weakened in a very remarkable manner, and if amblyopia occupy the left side, we may meet with a most noteworthy phenomenon, to which M. Galezowski has called attention, and which he designates the name achromatopsia…it was distinctly and repeatedly observed in one of our patients, a few weeks ago, from whom it has now completely disappeared.”14

He did not only find the symptom in women. In the sixth lecture of Leçons sur les maladies du système nerveux, “De l’hystérie chez les jeunes garçons (On hysteria in young boys),” Charcot mentioned “jeune Bl…” (only the first letters of the patient’s name were usually given), who presented with hemianesthesia “dans sa forme tout à fait classique (in its classic form),” including left-sided anesthesia. He pointed out that there is often a visual disturbance of the ipsilateral eye, a type of amblyopia. It was accompanied by a retraction of the visual field. In addition, visual acuity was impaired and dyschromatopsia or achromatopsia could be present.

Visual fields for certain colors, “le cercle de violet” for instance, could be reduced to zero. Blue and yellow could be the only colors perceived, but even these could disappear, a phenomenon that was called achromatopsia. “Je dois la signaler, parce qu’elle se rencontre non seulement chez la plus grande parties des femmes hystériques que nous avons observées, mais encore chez les sujets mâles dont nous parlerons bientôt (I must point this out, because it occurs not only in the majority of the female hysterics we have observed, but also in the male subjects we will discuss shortly)” and he continued by citing a case observed by Henri Parinaud (1844-1905), one of his collaborators.15

Art and Hysteria From Another Perspective

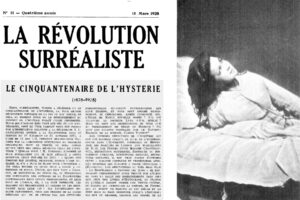

Figure 7. Aragon’s and Breton’s 1928 publication in La Révolution surréaliste “Le cinquantenaire de l’hystérie (1878-1928)”.14 The publication was accompanied by six photographs, by Paul Regnard of Charcot’s famous patient Augustine Gleizes, with the legend “Les attitudes pasionelles en 1878” (from23).

In contrast with the above, a different association between hysteria and art can be read in Louis Aragon’s (1897-1982) and André Breton’s (1896-1966) manifesto to celebrate the 50th anniversary (1878-1928)16 of the invention of hysteria. (See Figure 7.) They were important founders of surrealism, for which Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. In their 1928 publication “Le cinquantenaire de l’hystérie (1878-1928),” the year 1878 indicated the year in which Charcot’s methodology with respect to the study of hysteria, which he studied since 1872, moved from clinical observation to experiment, applying hypnosis as a diagnostic tool:17

“Nous, Surréalistes, tenons à célébrer le cinquantenaire de l’hystérie, la plus grande découverte poétique de la fin du XIXe siècle, et cela au moment même où le démembrement du concept de l’hystérie paraît chose consommée. Nous qui n’aimons rien tant que ces jeunes hystériques, dont le type parfait nous est fourni par l’observation relative à la délicieuse X.L. (Augustine — one of the patients, who became well-known) entrée à la Salpêtrière dans le service du Dr Charcot le 21 octobre 1875, à l’âge de 15 ans 1/2, comment serions-nous touchés par la laborieuse réfutation de troubles organiques, dont le procès ne sera jamais qu’aux yeux des seuls médecins celui de l’hystérie?”

“(We Surrealists wish to celebrate the 50th anniversary of hysteria, the greatest poetic discovery of the late 19th century, at a time when the dismemberment of the concept of hysteria seems complete. We who love nothing so much as these young hysterics — the perfect type of which is provided by the observation relating to the delightful X.L. (Augustine — one of the patients, who became well-known), who entered Dr. Charcot’s department at the Salpêtrière on Oct. 21, 1875, at the age of 15 1/2. How can we be moved by the laborious refutation of organic disorders, whose trial will only ever be, in the eyes of doctors, that of hysteria?)”

However, the year could also have been chosen for the extensive description of Charcot’s patient Augustine.18 Aragon and Breton concluded : “L’hystérie n’est pas un phénomène pathologique et peut, à tous égards, être considérée comme un moyen suprême d’expression. (Hysteria is not a pathological phenomenon and can, in every respect, be considered a supreme means of expression).”

Breton and Aragon considered hysteria as “the greatest poetic discovery of the latter part of the century.” In their lyrical homage, they take distance from Charcot’s pupil Joseph Babinski (1857-1932), under whom Breton had been a student before he decided to leave medicine, and who had reduced hysteria to suggestion.19

In Conclusion

As far as I have been able to verify, Charcot never referred to dyschromatopsia or achromatopsia as a problem among artists. The connection between supposed visual disturbances of artists and the introduction of Impressionism was made by critics, who were aware of Charcot’s lectures in the Salpêtrière. Hysterical dyschromatopsia, which today we would call functional dyschromatopsia, has hardly been described after the period of the above discussion and even functional blindness is rare.

Today, the terms dyschromatopsia and achromatopsia refer to color vision disorders caused by a retinal disorder, affecting men more than women. Cerebral achromatopsia is a rare condition characterized by loss of color vision due to a cerebral etiology and generally believed to result from significant bilateral occipitotemporal damage.20 Despite this evolution since the late 19th century regarding the observation and interpretation of such symptoms in patients, it is interesting to see how these symptoms were then attributed to artists, who were developing a new style in the visual arts.

Finally, I would like to refer to a recent article in which medical historian Toby Gelfand describes an unpublished article by Charcot in which he put forward a psychological explanation for hysteria.21,22 •

References:

- Goetz CG, Bonduelle M, Gelfand T. Charcot. Constructing Neurology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Meige H. Charcot Artiste. Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière 1898 ;11:489-516.

- Koehler PJ. The stone of madness: Charcot’s interest in a copy after Pieter Bruegel Sr. as referred to by Henry Meige. J Hist Neurosci. 2024 May 28:1-13. See also Marriage at Cana, Norton Simon Museum; accessed February 1st, 2025.

- King R. De omwenteling van Parijs. Over de geboorte van het Impressionisme (original English title: The Judgment of Paris). Amsterdam, De Bezige Bij, 2006, pp.432-6.

- Guffey E. The ‘Malady’ of Impressionism; How Claims of Disability Haunted the Modernist Movement. Art in America. October 2022, pp. 68–75.

- Ronetti A. Voir violet. Les limites du visible et la violettomanie des impressionnistes. Histoire de l’art. 2021 : 88 : 143-56.

- Koehler PJ. Charcot, la salpêtrière, and hysteria as represented in European literature. Prog Brain Res. 2013;206:93-122.

- Smeets M. Een Parijse Hollander. Joris-Karl Huysmans. Hilversum, Verloren, 2021.

- Academic study on Huysmans on a website by King B Biographical; accessed January 19th, 2025.

- Baldick R. The Life of J.-K. Huysmans. Oxford, Clarendon, 1955, p. 62.

- Marquer B. Les Romans de la Salpêtrière. Réception d’une scénographie clinique: Jean-Martin Charcot dans l’imaginaire fin-de-siècle. Genève, Droz, 2008.

- Huysmans JK. L’art moderne. 2nd ed. Chapter on L’exposition des indépendants en 1880. Paris, Plon, 1908, p. 104.

- Charcot JM. Leçons du mardi à la Salpêtrière: policliniques, 1887-1888/professeur Charcot; notes de cours de MM. BLin, Charcot [fils] et Colin. Paris, Bureau du Progrès Médical/Delabaye & Lecrosnier, p. 294.

- Charcot JM. Lectures on the diseases of the nervous system. Transl. by Sigerson G. Vol. I. London, New Sydenham Society, 1877, pp. 249-50.

- Charcot JM. Leçons sur les maladies du système nerveux. Œuvres Complètes III. Paris, Lecrosnier & Babé, 1890; pp. 80-96.

- Aragon L, Breton A. Le cinquantenaire de l’hystérie (1878-1928). La Révolution surréaliste no. 11, March 15, 1928.

- Micale MS. Hysteria and its historiography: A review of past and present writings (II). Hist Sci 1989; 27: 319–51.

- Bourneville DM, Regnard P. Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Vol. 2, Paris, Bureaux du Progrès Médical / Delahaye, 1878, pp. 123-86.

- Haan J, Koehler PJ, Bogousslavsky J. Neurology and surrealism: André Breton and Joseph Babinski. Brain. 2012 Dec;135(Pt 12):3830-8.

- Bouvier SE, Engel SA. Behavioral deficits and cortical damage loci in cerebral achromatopsia. Cereb Cortex. 2006 Feb;16(2):183-91.

- Gelfand T. Dreams: Charcot’s Last Words on Hysteria. Bull Hist Med. 2024;98(1):1-25.

- Gelfand T. Charcot and the psychology of hysteria, with special reference to a never published final case history. J Hist Neurosci. 2024 Aug 26:1-11.

- Bourneville DM, Regnard P. Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Vol. 2, Paris, Bureaux du Progrès Médical / Delahaye, 1878, pl. XIX between pp. 162 and 163.