By Douglas J. Lanska, MD, MS, MSPH, FAAN

Douglas Lanska

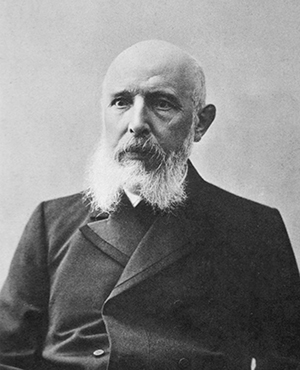

In 1873, Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1841-1912) [below]discovered rod-shaped bodies — Mycobacterium leprae — in leprous nodules. Initially unable to stain these bodies, he only tentatively suggested that they resembled bacteria, which led to a later priority dispute with Albert Neisser (1855-1916) when Neisser was able to stain the organisms and then claimed priority for the discovery. Although Hansen was convinced that leprosy was an infectious disorder, he was unable to cultivate the organism and unable to transmit the disease to animals, despite 12 failed attempts to transmit the disease to rabbits by inoculation.

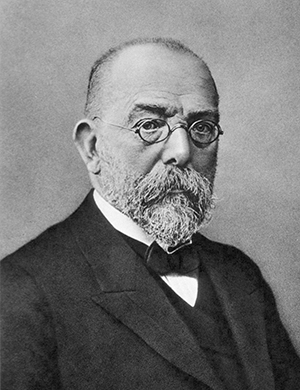

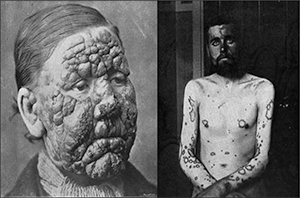

In 1875, Hansen had been appointed as medical officer of health for leprosy in Norway and as the resident physician at the Bergen Leprosy Hospital. After corresponding with German physician and pioneering microbiologist Robert Koch (1843-1910) in Breslau, Hansen decided to attempt human-to-human inoculations, and specifically to inoculate leprous tissue from a patient with lepromatous (multibacillary) leprosy into patients with tuberculoid (paucibacillary) leprosy [below right] to determine whether he could produce manifestations of lepromatous leprosy.

Robert Koch. Public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

While Hansen had already achieved some professional renown for his studies of leprosy, his patients found him aloof and high-handed. On Nov. 3, 1879, while on rounds at the Bergen Leprosy Hospital, Hansen instructed a 33-year-old patient with the “anesthetic type of leprosy,” Kari Nielsdatter Spidsøen, to accompany him to his office as he indicated he wanted to speak to her. There, she saw that he had a sharp-cutting instrument in his hand which he brought up to her eye, while she held him off with her arms. After she was calmed down by one of the other doctors in the room, Hansen succeeded in his goal of inoculating leprous material from another patient under the conjunctiva of her eye with a cataract knife.

Gerhard Armauer Hansen. (Public domain. Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine)

The patient reported this to the hospital pastor, Pastor Grönvold, who in turn forwarded the complaints to legal authorities who charged him with causing bodily harm to an innocent patient. According to the transcript of the court proceedings, Hansen “admitted that he was not justified in carrying out the operation as he had neither obtained her permission in advance, nor told her of his aim in doing it. He had omitted seeking informed consent for the procedure “as he took for granted that the [patient] would not regard the experiment from his point of view, and if something happened [e.g., a lepromatous lesion developed that might threaten her vision], he was sure he could get the affection under control.”

Despite the criminal complaint against him, Hansen boldly expressed to the court his self-righteous belief that he was justified in these actions: … even if the subject should have some pain, because he had chosen a subject who had suffered from leprosy for many years, and therefore would not be exposed to a new disease. He was quite sure that there was no risk of loss of vision, even if the inoculation should have resulted in a nodule. He himself had several times extirpated nodules from eyes without any trouble, and had succeeded in saving the eyesight. … The great scientific and national importance of finding the answer to the question [of the transmissibility of leprosy] had therefore forced him to act as he did.

Maculo-anesthetic (tuberculoid or paucibacillary) leprosy (left) and lepromatous (multibacillary) leprosy (right). Tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by hypopigmented skin macules and anaesthetic patches from damaged peripheral nerves, while lepromatous leprosy is characterized by symmetric skin lesions, nodules, plaques and thickened dermis with detectable nerve damage typically late in the illness. (From Walker, 1905)

Although Hansen’s colleagues supported him with various post hoc justifications, it was clear to the court (with Hansen’s own admission) that, in his zealousness to prove the infectious nature of leprosy, he had misused his position of authority by trying to intentionally transmit a disease to a patient placed in his care without the patient’s consent.

Hansen was convicted and in consequence lost his post at the Leprosy Hospital in Bergen, but in a legal-political compromise he retained his position as chief medical officer for leprosy in Norway. The case had little effect, though, on Hansen’s professional reputation, and he continued with his scientific studies. Nevertheless, as Norwegian microbiologist and historian Thomas M. Vogelsang (1896-1977) concluded, the legal decision emphasized “that even a celebrated scientist is bound to obey the law of the land, and that it is the court’s duty to protect every citizen also against encroachments from more influential persons.”

References

Blom K. Armauer Hansen and human leprosy transmission: Medical ethics and legal rights. Int J Lepr 1973;41:199-207.

Lock S. Research ethics – a brief historical review to 1965. J Intern Med 1995;238:513-520.

Marmor MF. The ophthalmic trials of G.H.A. Hansen. Survey Ophthalmol 2002;47:275-287.

Vogelsang TM. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen: 1841-1912: The discoverer of the leprosy bacillus. His life and his work. Int J Lepr 1978;46:257-332.

Walker NP. An Introduction to Dermatology. Third edition. Philadelphia: William Wood and Co.