By Raad Shakir

Raad Shakir

Summer in the Northern Hemisphere is a holiday season, and it is a time for reflection on what has happened during the first half of the year. The theme of this column is the willingness of many of our neurological societies to lend a hand to those hard-working colleagues who practice in less prosperous parts of the world.

There are two endeavors, which I would like to concentrate upon. There is a huge need for exposure to modern technology and method of practice, which is not available in the developing world. This can be fulfilled by short-term visits to centers of excellence. The WFN started enquiring from member societies to see the feasibility of such programs and, as importantly, to explore the possibility of funding. The response thus far has been most rewarding. It started with the Turkish Neurological Society fully funding a four- to six-week visit for two neurologists from Africa nominated by the WFN. The program is now in its third year and was soon followed by the Austrian and the Norwegian neurological societies.

Members of the neurophysiology training team in Rabat, Morocco, with Prof. Mostafa Elaloui, head of department (second row, far left) and Mohamed Albakay Mali, the first WFN fellow (second row, second from left).

This just reinforces the purpose of the WFN in being a catalyst for training and international collaboration. Our three member societies have provided the funding and the time to welcome young African neurologists to their neurological departments and provide them with intense exposure to the latest technologies and guide them in ways of improving their practices in their home departments.

The WFN is in negotiation with other societies in the developed world to follow suit and take more young individuals not only from Africa, but also from all other parts of the world. The program can perhaps be best applied within regions or partnering two or three of the six regions of the WFN. This is the function of the Regional Liaison Committee of the WFN. Perhaps the best working example of regional department-to-department visits is the European region, and the European Academy of Neurology has shown its willingness to extend the program across the Mediterranean to involve the EAN associate member countries. I have to say that such acts of real interaction in international training only demonstrate the openness and generosity of neurological associations in aiding neurologists who just happen to be in a part of the world which lacks funding and organization.

WFN Education Committee accreditation visit at Qasr El Aini University Hospital in Cairo, Egypt.

If we take this further, reciprocity is perhaps one of the answers. Many young neurology trainees from the more developed world would love the opportunity to train for short periods in the developing world. This will enrich their experiences both professionally and socially. Although this is now widely practiced, it is mostly, if not exclusively, on a personal basis. Committing neurological societies in the developing world to be involved and responsible as hosts would be most helpful to those who need guidance when joining a neurological service in the developing world. This double link is the aim of the WFN.

The second activity, which is most important, is training neurologists on their own continents. This has started in Africa by the Moroccan Society of Neurology. Rabat was visited and accredited as a WFN Training Center, and the first intake of training started in September 2014. World Neurology is advertising for the second training intake this year. Again the generosity and willingness to help is most evident. The University of Mohammed V in Rabat is offering the training for free with no tuition fees required. The WFN is providing living expenses for trainees. This has worked well and should continue to prosper. What is on offer is either a fully certified four-year training program culminating in an exit examination and a diploma from the University of Rabat or a one-year training fellowship for those who have been trained elsewhere and wish to subspecialize in a specific field.

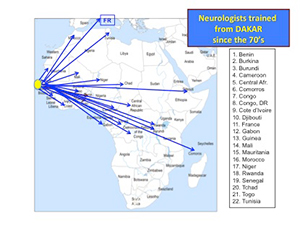

Figure 1. African trainees in Dakar, Senegal.

In view of the great need in Africa, the WFN entered negotiations with the Egyptian Neurological Society. This was most successful as the University of Cairo, one of the oldest in North Africa, which has kindly agreed to do the same, as there is an urgent need for Anglophone training in addition to the Francophone training in Rabat. The department in Qasr El Aini’s sprawling teaching hospital was inspected and accredited by the WFN Education Committee. Again the cost to the WFN is minimal, and the trainees will start in September 2015.

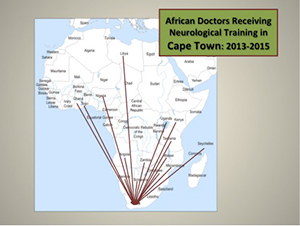

The needs are great. The WFN has therefore entered negotiations with two other major centers in Africa. Two have applied to be training centers: Dakar, Senegal, with its long tradition of training in West Africa (Figure 1), and Cape Town, South Africa, with its history of training African neurologists (Figure 2). This will make four Training Centers, two Francophone and two Anglophone. In all these cities, trainees will receive their training in exactly the same way as local trainees, and at the successful conclusion will be certified as specialists by the awarding institution and by the WFN, having been trained in an accredited program.

Figure 2. African neurologists trained in Cape Town, South Africa.

As these programs grow, there will be a definite need for diversifying funding. At this moment, the WFN is just about able to fund a small number of trainees. However, as the numbers increase in an exponential manner, we need to find outside sources of finance. The WFN is trying to approach funding and philanthropic organizations for support. I would be most grateful for all of our readers to advise the WFN and me directly or through their national societies if they can think of a possible source of funding we can approach.

In the two examples, neurological societies in the developed and the developing world have come up trumps. They have demonstrated their willingness to help in constructive and practical manners with ways of collaborating with their fellow neurologists. They do this with a great degree of selflessness and with the guiding principle of promoting our specialty. For that, my fellow WFN trustees and I are most grateful.