By Kiran Thakur, MD, and Sarosh Katrak, MD, DM, FRCP(E)

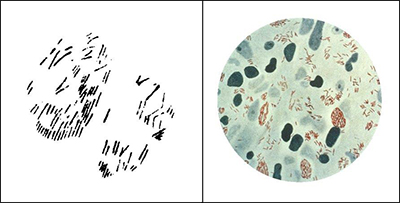

Neurological infections continue to ravage populations in developing and developed countries. In many regions, central nervous system (CNS) opportunistic infections due to AIDS and tropical diseases remain a major contributor to morbidity and mortality.

In resource-rich settings, where new immunomodulatory medications are being frequently used, CNS infections are being increasingly recognized. There are a growing number of emerging and re-emerging neurotropic infectious diseases, and proper diagnosis and management often require neurologic expertise that may not be available in certain global regions.

Despite significant scientific advances in the field, the burden of undiagnosed neurological infections remains unacceptably high. Major research gaps exist in our understanding of the pathogenesis and cost-effective diagnostics, as well as the CNS penetration and optimal treatment schedules of many neurological infections.

As co-chairs of the newly established applied research group in neurological infections, we are excited to enhance the education, training and research in neurological infections to the global neurology community. The World Federation of Neurology is well positioned to make a major impact in this field through its representation of more than 100 countries, many of which have neurologists with expertise in neurological infections.

We hope to engage experts in neurological infections in collaborative research and educational projects and those interested in improving their knowledge of neurological infectious diseases. We encourage those interested in participating to become members and participate in the educational and research endeavors of our group.

Research Goals

- Surveillance of emerging and re-emerging neurological infections

- Continued vigilance in understanding the burden of CNS opportunistic infection risk in patients on immunomodulatory therapies

- Surveillance of undiagnosed infectious diseases in the global community

- Enhanced pathogen discovery testing globally, with increased access to advanced testing in resource-limited settings

- Drug-development trials, including studies on CNS penetration of medications for neurological infections and setting drug-dosing and treatment protocols specific for CNS infections

Training and Educational Goals

- Develop and enhance educational sessions on neurological infections at the World Congress of Neurology meetings

- Training sessions in neuroinfectious diseases for general practitioners and neurologists

- Develop training modules on neurological infections with a focus on acute meningitis/encephalitis, chronic meningitis, opportunistic infections in immunosuppressed patients, viral encephalitis and tropical neurology

The neurosonology team members created a training program, titled “The Neurosonology Professional Diploma.” The course is designed in five comprehensive modules to be presented annually from October to June, and provides candidates with basic theory and practical skills in commonly applied neurosonology techniques. The NSRG of the World Federation of Neurology reviewed the program and certified it as an outstanding high standard teaching program. Many candidates already expressed their interest in it. Full details of the program can be found at

The neurosonology team members created a training program, titled “The Neurosonology Professional Diploma.” The course is designed in five comprehensive modules to be presented annually from October to June, and provides candidates with basic theory and practical skills in commonly applied neurosonology techniques. The NSRG of the World Federation of Neurology reviewed the program and certified it as an outstanding high standard teaching program. Many candidates already expressed their interest in it. Full details of the program can be found at

The medical book publishing industry is challenged nowadays to turn out products quickly and efficiently, lest the rapid dissemination of today’s scientific advances through the Internet render the content of a book out of date on arrival. The second edition of Murat Emre’s “Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease” has avoided this fate, in large part because of the organizational skill of the editor and his recruitment of the same authoritative thought leaders that contributed to the first edition in 2010. Hence, this continuity of authorship has allowed for a seamless update of the topics covered before.

The medical book publishing industry is challenged nowadays to turn out products quickly and efficiently, lest the rapid dissemination of today’s scientific advances through the Internet render the content of a book out of date on arrival. The second edition of Murat Emre’s “Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease” has avoided this fate, in large part because of the organizational skill of the editor and his recruitment of the same authoritative thought leaders that contributed to the first edition in 2010. Hence, this continuity of authorship has allowed for a seamless update of the topics covered before. As Dr. Emre observes in his elegant introduction, cognitive impairment as an essential feature of PD was mostly unrecognized by James Parkinson in his essay on the Shaking Palsy (1817) because lack of treatment doomed its victims to a severe physical disability and a shortened lifespan. The stark reality of cognitive impairment in advanced PD became apparent only after the remarkable benefit of levodopa enabled people with PD to function better physically and thereby live longer. Well-designed, long-term cohort studies in the early part of this century revealed not only the shocking news that 70-80 percent of people with PD would develop dementia as they aged and progressed, but also that subtle cognitive abnormalities, particularly in executive function, were prevalent in a sizeable minority at early stages of the disease.

As Dr. Emre observes in his elegant introduction, cognitive impairment as an essential feature of PD was mostly unrecognized by James Parkinson in his essay on the Shaking Palsy (1817) because lack of treatment doomed its victims to a severe physical disability and a shortened lifespan. The stark reality of cognitive impairment in advanced PD became apparent only after the remarkable benefit of levodopa enabled people with PD to function better physically and thereby live longer. Well-designed, long-term cohort studies in the early part of this century revealed not only the shocking news that 70-80 percent of people with PD would develop dementia as they aged and progressed, but also that subtle cognitive abnormalities, particularly in executive function, were prevalent in a sizeable minority at early stages of the disease.

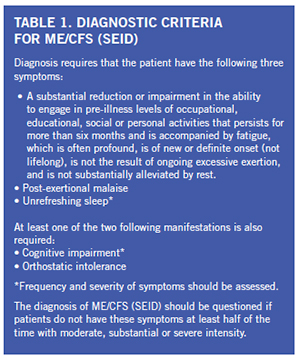

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.

There is significant economic burden associated with this condition as one quarter of patients are bed- or house-bound at some time during their illnesses. ME/CFS patients have been found to be more functionally impaired than patients with other disabling illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, depression, multiple sclerosis and end-stage renal disease. Unemployment rates range from 35 to 69 percent in these patients. ME/CFS patients have loss of productivity and high medical costs that lead to an estimated economic burden of $17 billion to $24 billion yearly.