By Soma Sahai-Srivastava, MD

Soma Sahai-Srivastava

Cambodia is a Southeast Asian country of 15 million people with a per capita annual income of $1,080. For 100 years until 1953, it was a French colony, followed by formation of a kingdom. In 1970, civil war led to the rise of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge communist agenda, a classless society with no economy. Under Pol Pot (1975–1979), the educated class was targeted, and 2 million to 3 million Cambodians were executed. Only a handful of doctors remained, as many died or left the country.

In my many trips to Cambodia in the last decade as a solo volunteer, I realized there are no short-term volunteer opportunities for neurology clinical care, unlike other specialties, such as emergency medicine, pediatrics and surgery. No neurology outpatient clinics or inpatient specialized programs existed until recently. There were only three neurologists in the country reported in 2012 (Loo, 2012). Currently there is no adult or pediatric neurology residency program. Pediatric patients with epilepsy, autism or developmental disorders are treated in a tertiary care mental health clinic by psychiatrists. The first internal medicine residency program launched in 2011.

Residents at the University of Health Sciences undergo a two-week hands-on session covering internal medicine, psychiatry and neurosurgery.

I realized that our first priority was clinical education and curriculum development rather than patient care, since neuroscience education at all levels —undergraduate, medical school and postgraduate — is lacking in modern Cambodia. There are only four pathologists in the country; none are neuropathologists. Anatomy teaching does not include 3-D models or cadaver or animal dissection. With the help of an educational two-year grant award from the WFN, a neurology outreach program for Cambodian health care professionals was convened July 25–Aug. 10, 2015, in Cambodia.

Our first goal was the development of appropriate undergraduate and residency neurology curriculum in collaboration with the only government academic medical center, the University of Health Sciences (UHS), which sets the curriculum for undergraduate and postgraduate education in Cambodia for all academic institutions. We met with educational leaders and reviewed the current curriculum, especially in context of a standard Western neurology curriculum. Challenges to establi

shing a standard neuroscience curriculum were identified and included lack of cadaver training and neuroanatomists in Cambodia. We decided to establish of two neurology teaching modules for their Train-the-Trainers program— a basic neurosciences module and a clinical neurology module.

Our second goal was to provide workshops on basic clinical neurology skills to health care professionals in all the major cities in Cambodia. We conducted a two-week hands-on session for 50 residents at UHS in Phnom Penh, covering internal medicine, psychiatry and neurosurgery. Tools used for these seminars included PowerPoint presentations, a brain model for basic neuroanatomy, a neurological examination video, neurology tool kits for neurological examination, and pre-test and post-test outcome evaluations. We produced a video on neurological examination and used brain models as a teaching tool. Fifty neurology tool kits were distributed to the residents, the contents of which included a Snellen eye chart, penlight, dermatome chart, tongue blade, reflex hammer, tuning fork and pins. We also taught at the University of Puthisastra, where 150 medical students received three days of neurology education.

Teaching rounds were held for a neurology inpatient team comprising internal medicine residents and faculty from several hospitals, including Calmette Hospital, Kossamak Hospital and Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital in Phnom Penh. In addition, we visited the Children’s and Adolescent Mental Health Referral Center at Chey Chumneas Hospital in the Takhamu-Kandal Province, where we held a half- day seminar and hands-on teaching session on neurological examination along with distribution of neurology tool kits. In the beautiful colonial city of Battambang, we conducted teaching rounds in the outpatient clinic over two consecutive days for children up to 18 years with neurological disorders, including epilepsy and developmental disorders. This program was held at the Outpatient Free Clinic of the Battambang Catholic Church. We also trained physiotherapists in the department of physiotherapy on basic neurological skills.

We then traveled to Siem Reap, where we met with the Deputy Director of the Apsara Authority, the government agency that supervises all national monuments and will be setting up future workshops at the 400-square-kilometer Angkor Heritage Complex (one of the seven ancient wonders of the world) in Siem Reap for health care professionals.

Some of the lessons learned during our trip:

- Barriers to global neurology in developing countries include lack of an organized clinical setup for patient care.

- It is important to understand the current state of neuroscience curriculum to determine the needs.

- Often one needs to return to the drawing board with basic neuroscience.

- Initiate clinical education of existing medical docs (our focus: psychiatry, internal medicine and neurosurgery).

- Developing many levels of peer-to-peer relationships improves networking and learning (e.g., resident to resident, faculty to faculty).

We will return to Cambodia in June 2016 for two weeks with the following objectives:

- To provide an additional year of continuity to our neurology basic training program and provide neurology toolkits for Cambodian health care professionals.

- To train Cambodian neurology trainers in two neurology modules: basic and clinical neurosciences.

- To establish and deliver the first neurology skill lab for international program students at UHS.

- To establish and deliver a revised curriculum and course syllabus design for a neurology module undergraduate medical students.

- To develop curriculum for neurology residency training, with the goal of assisting in readiness in establishing the first residency program in the fall of 2016.

- To develop culturally, geographically and medically relevant assessment exercises that include formative assessment (i.e., pre-test, post-test) and summative exams with rating scores that are consistent with learning objectives.

“Nothing we can do.” This is a commonly used phrase when discussing the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with recently diagnosed patients. It is often uttered at a time when patients are at their most vulnerable. They have just discovered they have a relentlessly progressive neurodegenerative disease and simultaneously they are left with the impression that they are on their own because there is “nothing we can do.”

“Nothing we can do.” This is a commonly used phrase when discussing the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with recently diagnosed patients. It is often uttered at a time when patients are at their most vulnerable. They have just discovered they have a relentlessly progressive neurodegenerative disease and simultaneously they are left with the impression that they are on their own because there is “nothing we can do.”

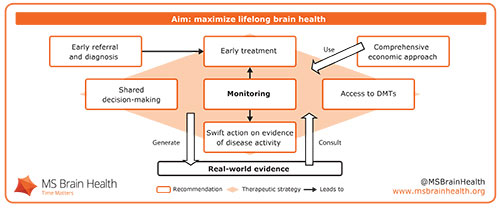

Professor Tim Vollmer outlined the brain health perspective on MS, presenting recent data underpinning its scientific basis. People with relapsing–remitting MS can lose brain volume up to seven times faster on average than age-matched controls, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of clinical trials.1 Up to a point, this damage can be compensated for by neurological reserve — the brain’s finite capacity to reroute signals or adapt undamaged areas to take on new functions.2,3 Preserving neurological reserve protects against cognitive decline4 and physical disability progression5 in people with MS. Once neurological reserve is exhausted, however, the long-term progressive phase of the disease will be unmasked, Vollmer argued. Adopting a therapeutic strategy that preserves neurological reserve by minimizing disease activity therefore should be of primary concern when people with MS and their clinicians make treatment decisions.

Professor Tim Vollmer outlined the brain health perspective on MS, presenting recent data underpinning its scientific basis. People with relapsing–remitting MS can lose brain volume up to seven times faster on average than age-matched controls, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of clinical trials.1 Up to a point, this damage can be compensated for by neurological reserve — the brain’s finite capacity to reroute signals or adapt undamaged areas to take on new functions.2,3 Preserving neurological reserve protects against cognitive decline4 and physical disability progression5 in people with MS. Once neurological reserve is exhausted, however, the long-term progressive phase of the disease will be unmasked, Vollmer argued. Adopting a therapeutic strategy that preserves neurological reserve by minimizing disease activity therefore should be of primary concern when people with MS and their clinicians make treatment decisions.

Neuroimaging is an important adjunct to clinical neurology. We cannot easily examine the brain directly. The neurologic exam is designed to allow us to make reasonable inferences about abnormalities of neurologic functioning, and neuroimaging helps us visualize the brain. This significantly enhances our ability as clinicians to diagnose the cause of a neurological abnormality and monitor response to an intervention. This is particularly true in neurodegenerative diseases, where the neurologic exam has been immensely assisted by neuroimaging. Indeed, with advances in neuroscientific knowledge, novel imaging techniques have been developed to provide additional insights into neurological functioning in health and disease.

Neuroimaging is an important adjunct to clinical neurology. We cannot easily examine the brain directly. The neurologic exam is designed to allow us to make reasonable inferences about abnormalities of neurologic functioning, and neuroimaging helps us visualize the brain. This significantly enhances our ability as clinicians to diagnose the cause of a neurological abnormality and monitor response to an intervention. This is particularly true in neurodegenerative diseases, where the neurologic exam has been immensely assisted by neuroimaging. Indeed, with advances in neuroscientific knowledge, novel imaging techniques have been developed to provide additional insights into neurological functioning in health and disease.